Ilūkstes jezuītu klosteris. Būvvēsture un arhitektūra

Ilūkste Jesuit Monastery. Construction History and Architecture

Author(s): Ilmārs DirveiksSubject(s): Cultural history, Architecture, Visual Arts, 18th Century, History of Religion, History of Art

Published by: Mākslas vēstures pētījumu atbalsta fonds

Keywords: Ilūkste Jesuit Monastery; Jesuit architecture; Jesuit missions; Jesuit monasteries; Catholic Church; Duchy of Courland and Semigallia; Zyberg family

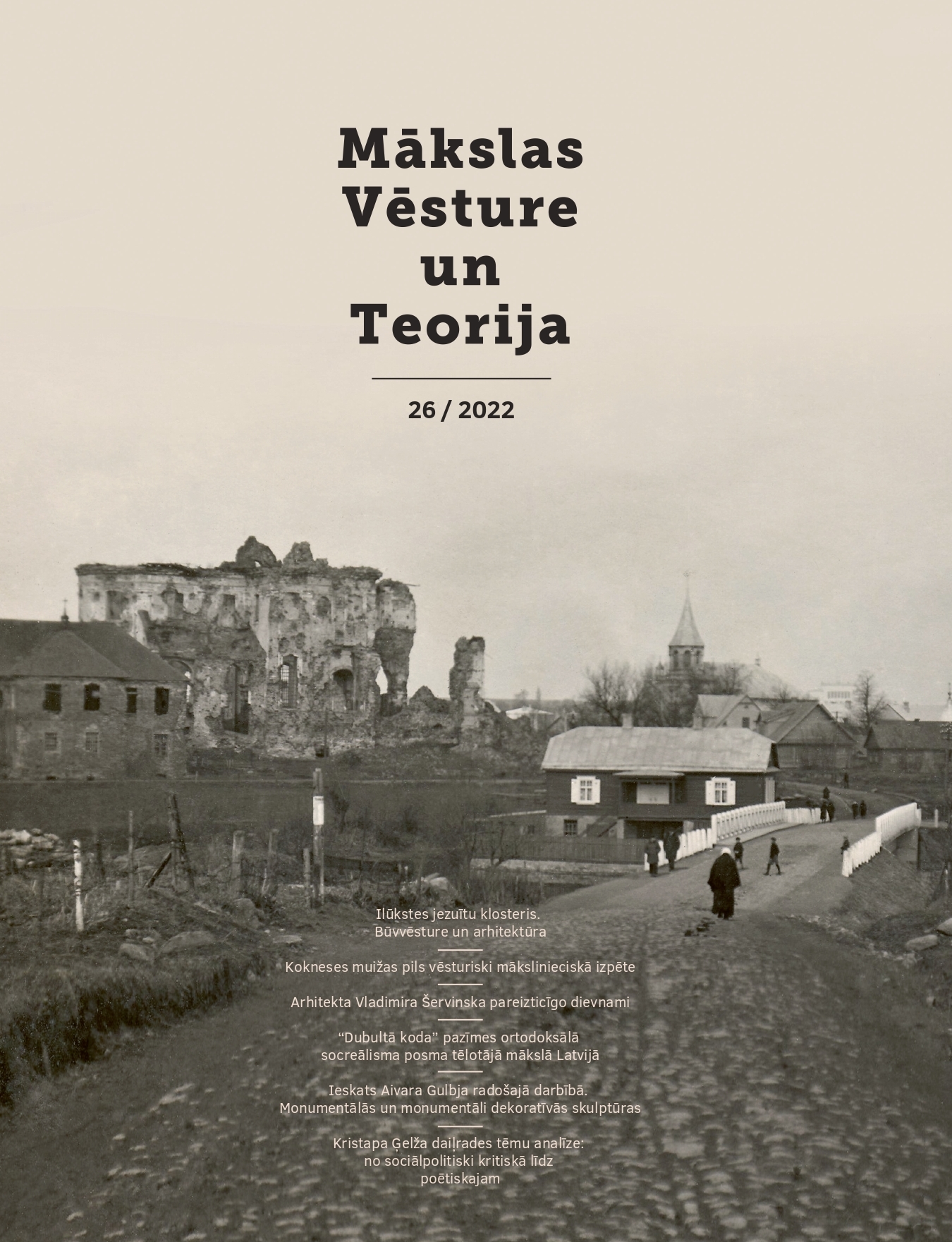

Summary/Abstract: Today Ilūkste resembles a rather remote town for many. It was mentioned as a small village in the mid-16th century. Gradual development began here after the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia was founded. Old Believers, Lutherans and Catholics built their churches there. Support for Jesuits by the landowning Zyberg family gradually made Ilūkste one of the Duchy’s main Catholic centres. St. Ursula’s Catholic Church built in the mid-18th century was the largest Catholic Church in the Duchy; together with the college complex it equalled the Aglona religious and educational centre on the right bank of the River Daugava. The imposing church vanished from the Ilūkste landscape in the historical turmoil of the 20th century. The church was blown up during the First World War and its stone remains were fully removed as late as 1956. After the Second World War, the former monastery building increasingly faded into oblivion. Although the history of Ilūkste Jesuit college and St. Ursula’s Church has been much studied already, providing a good, professional theoretical basis, research of former monastery buildings was not carried out before autumn 2021. Thus the opportunity arose to gather valuable new information about this important object in Latvia’s cultural history. Ilūkste Jesuit monastery (college) building and the so-called “side building” are parts of the largest Jesuit residence in the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. The residence once included St. Ursula’s Church, the nearby monastery and (school?) building and to the south, several outbuildings and a garden (currently with only approximately known boundaries). In the monastery’s former inner courtyard and a precisely undefined territory there has been a cemetery since at least the 17th century. Today the Jesuit college includes two objects – the monastery building and the “side building”. The monastery building was built in two stages. The south block was built in 1747–1748, the east block – in 1753 while the interior was completely finished only in 1757. However, the monastery remains historically incomplete, as the planned west block was never built. The monastery building has fully retained its initial layout with later additions, not destructive enough to affect the original significantly. Only the structure connecting the building to the church was lost. Small changes to the volume were brought by the relatively flat roof built in 1919–1920. The monastery building has vaulting on all floors. During the First World War, about one third of all vaulting in the east block was lost and replaced with flat wooden constructions. Vaulting, diverse wall niches, large window openings, corridors and a staircase form the highly authentic 18th century Jesuit monastery interiors. The function of the basement with places for heating (?) devices and ventilation ducts in the walls has yet to be fully studied. The complex constructive solutions of the monastery building show high-level Jesuit architecture created by experienced executors. Although the Ilūkste monastery building is smaller than the neighbouring Daugavpils college, the designers’ and masons’ skills and implementation are totally comparable. The monastery building’s façades remained unplastered for a long time. Decorative plastering was likely applied to the south façade on the first-floor level as late as the 19th century. Conversely, original plastering has survived in almost all interiors. No evidence has been found yet about artistically valuable wall and ceiling décor. A simple 19th century decorative painting system was uncovered, consisting of a dark socle part and stencilling with roller brush from the first half of the 20th century. Two vaulted, mid-18th century south-block cell plafonds are among the most artistically significant finish examples rarely preserved in Latvia. The building south of the monastery initially had two storeys and a monastery-side entrance. Façades have decorative lesenes (pilaster strips) with specially elaborated, moulded bases. The spatial composition of this “side building” is unusual in Latvia’s architectural context. There were two ground-floor premises at first. The larger west room had a wooden covering, three spacious wall niches and a window in the outer wall. The south side had a narrow, long, barrel-vaulted premise with two window openings, one in the east wall, and another in the north end facing the monastery. Truly surprising is the first-floor layout with one large, barrel-vaulted room. The east and west end walls had one window each. Stairs to the attic were built on the south side in the middle of the vault. The choice of such a covering for the large premise remains unexplained but it could be related to its special function. The school and theatre building played quite an important large role for the residence. Therefore, a lasting stone house built of bricks made at the new kiln would be logical. Hypothetically, the present building beside the monastery fits this function; it proved useful in 1748 when the wooden church burned down and a temporary chapel was arranged in the “theatre house”. Visual features, even without further studies, tell every practicing building specialist that they date back at least to the 18th century. If the experienced researcher of Jesuit architecture Jerzy Paszenda had visited Ilūkste in person, the “side building” would surely have caught his attention. The “side building” was constructed as a part of the new monastery’s envisioned stone complex. The building was architecturally completed in the 18th century with relief décor on its plastered façades. Analysing its spatial structure and archival information, up to now only theoretical speculations about its function are possible. The “side building” looks more like a school than a dormitory with separate sleeping quarters for disciples. The spatial structures of the old and the new building are similar, as the old school building had ground-floor classrooms and one large room upstairs – a theatre hall. The “side building” today reveals an analogous structure. Although the similarity is just formal, the aforementioned arguments allow the hypothesis that the “side building” of Ilūkste monastery was built in 1730 as a school and possibly also a theatre. It is typologically unique in the architecture of Latvia and the oldest building in present-day Ilūkste. Even if both stone buildings of Ilūkste monastery have suffered much during wars and were rebuilt in the second half of the 20th century, their initial spatial structure and much of original substance has survived. Considering the significance of this place in Latvia’s cultural history and the unique building typology, the former Ilūkste Jesuit college ensemble is certainly an outstanding monument of architecture and history whose true values have yet to be revealed.

Journal: Mākslas Vēsture un Teorija

- Issue Year: 2022

- Issue No: 26

- Page Range: 6-20

- Page Count: 15

- Language: Latvian

- Content File-PDF