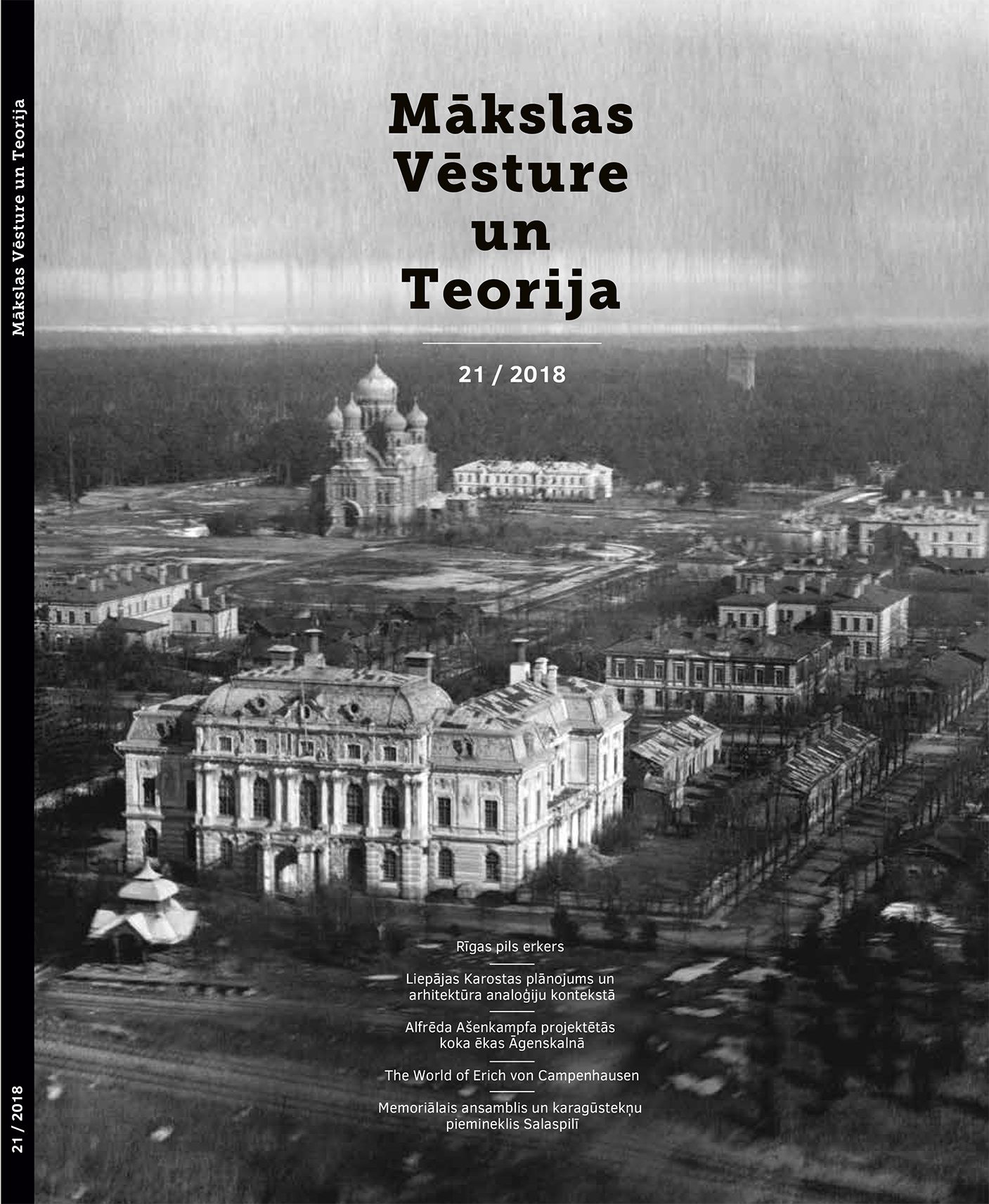

Memoriālais ansamblis un karagūstekņu piemineklis Salaspilī

The Salaspils Memorial Ensemble and Monument to Prisoners Of War

Author(s): Laila Bremša Subject(s): Architecture, Visual Arts, Social history, WW II and following years (1940 - 1949), Fascism, Nazism and WW II

Published by: Mākslas vēstures pētījumu atbalsta fonds

Keywords: Salaspils Memorial Ensemble; Salaspils concentration camp; monumental sculpture; Soviet sculpture; Latvian sculpture;

Summary/Abstract: The memorial ensemble on the site of the former Salaspils concentration camp (1967) and the nearby monument to Red Army prisoners of war (1968) are among the most significant Second World War memorials in Latvia’s Soviet-period art. After half a century since the opening of these monuments, the Soviet regime is gone and they no longer represent the official ideology. These monuments of artistic worth can now be reinterpreted and we can add new information to the history of their creation using the latest sources. The Soviet regime created the myth of the Salaspils death camp for several internal and foreign policy reasons, exaggerating the death toll by a factor of ten and the brutality of repressions. In contrast, the erection of a monument to dead Red Army prisoners of war was unusual in the Soviet period. As late as the collapse of the regime, prisoners of war were seen as traitors, self-evidently not deserving a monument. Both memorials stand in a territory where, according to the studies of Aleida Assmann and Siobhan Kattago, mutually exclusive narratives on the Second World War coexist. These ideas linger in the memories of the war witnesses as well as their closest descendants, embodied in various information carriers and maintained through memorial rituals. The Soviet narrative is largely about the suffering of the Russian people and their heroic mission as victors and liberators in the fight against German Fascism (Nazism) while the Eastern European and Latvian narrative focuses on the nation’s sufferings under two totalitarian regimes and remembers the Soviet occupation as the most destructive. Comprehensive research by historians (Heinrihs Strods, Kārlis Kangeris, Uldis Neiburgs, Rudīte Vīksne) who studied the Salaspils camp are significant in this context, effectively dismantling the Soviet myth. Scholars established that people did perish due to the repressive regime and harsh conditions but in much smaller numbers; no proof of heroic resistance, uprisings or distinct solidarity of prisoners were ever found.The concentration camp operated from 1941 to 1944; the buildings were burned down and thus no direct testimonies of its existence survived. The common practice of memorial art envisioned the preservation of concentration camp buildings for various reasons including as a counter to the information blockade on the very existence of camps and incredulity towards the stories of prisoners’ sufferings. Works on the memorial began in the late 1950s in the atmosphere of the victorious Soviet Union’s anti-Nazi propaganda and emotionally hopeful “thaw”. The Minister of Culture at the time, Voldemārs Kalpiņš, (1916–1995) played a significant role in this process. The memorial competition was announced in 1960, receiving 24 proposals that earned two second prizes, one third prize and four promotional prizes. Initially, the authors of awarded designs formed the creative team; the group proved to be too large with sculptors and architects of different ages, life experiences, creative styles and ideas about the relationship between architecture and sculpture within an ensemble. The team’s final version was approved only shortly before the ensemble’s opening in 1967. It included the competition winners, architects Ivars Strautmanis (1932–2017), Oļģerts Ostenbergs (1925–2012) and Gunārs Asaris (b. 1934), sculptor Oļegs Skarainis (1923–2017) and three contributors joining the group after the competition – sculptors Jānis Zariņš (1913–2000) and Ļevs Bukovskis (1910–1984), and architect Oļegs Zakamennijs (1915–1968). Sculptor Alvīne Veinbaha (1923–2011) won the competition but was not included in the group; with the help of her husband, art historian Jānis Kaksis (1926–2002), she managed to make and exhibit new models in a separate exhibition. They were appreciated but she was still not given the opportunity to contribute to the memorial. The design process of the ensemble was full of both personal and conceptual discord. Modernist architects wanted a more expressive, emotionally powerful sculpture while sculptors adhered to Latvian sculptural traditions, aiming to bring the topical “Severe Style” tendency or geometricised Socialist Modernism into the ensemble. Unusual and daring for that time was the attempt of the architects’ group to include the Moscow sculptor Ernst Neizvestny (1925–2016) in the team without official approval, based only on a mutual agreement. However, this was impossible in the given conditions. Later Skarainis admitted that Neizvestny’s sculptures had impressed him. Sources allow us to conclude that Skarainis’ role in the creation of the sculptural group had been greater than previously assumed. Work on the prisoners of war monument progressed quite smoothly. The architects’ group invited the sculptor Juris Mauriņš and their cooperation resulted in a concrete composition consisting of two stelae, a metaphor for the path of life cut short. One of the stelae is crowned with an expressive relief by Mauriņš. The memorial’s composition and relationships of architecture and sculpture aimed at marking the main elements of the former camp’s planning, making the visitor feel the spaces of suffering and annihilation. The ensemble’s most successful element is an asymmetrically constructed, massive geometric volume signifying the boundary between the spaces of “life” and “death”. It is built of monolithic concrete, retaining the mould impressions on the wall planes. The material and forms used were aimed at expressing harsh truth; one can say that Salaspils is the most consistent example of Brutalism in Latvia’ s conditions. Blocks marking the places of barracks and execution are also in line with this stylistics. The sculptural group occupies the main square and consists of free-standing concrete figures – a four-figure group “Protest”, containing a two-figure composition “Solidarity” and two separate figures “Red Front” and “Oath”. These sculptures voice the official Soviet ideology; a general narrative about the concentration camp is told in the figures “The Unbroken”, “The Infamous” and “Mother”. The placement of figures in space is well-balanced. The composition is best perceived while entering the ensemble and from the viewing platform built in the “wall”. The forms comply with the character of the “Severe Style” as developed in Soviet art in the early 1960s. On 7 February 2018, a museum exposition was opened in Salaspils, the ensemble was renovated and turned into an informative, up-to-date memorial.

Journal: Mākslas Vēsture un Teorija

- Issue Year: 2018

- Issue No: 21

- Page Range: 72-87

- Page Count: 16

- Language: Latvian

- Content File-PDF