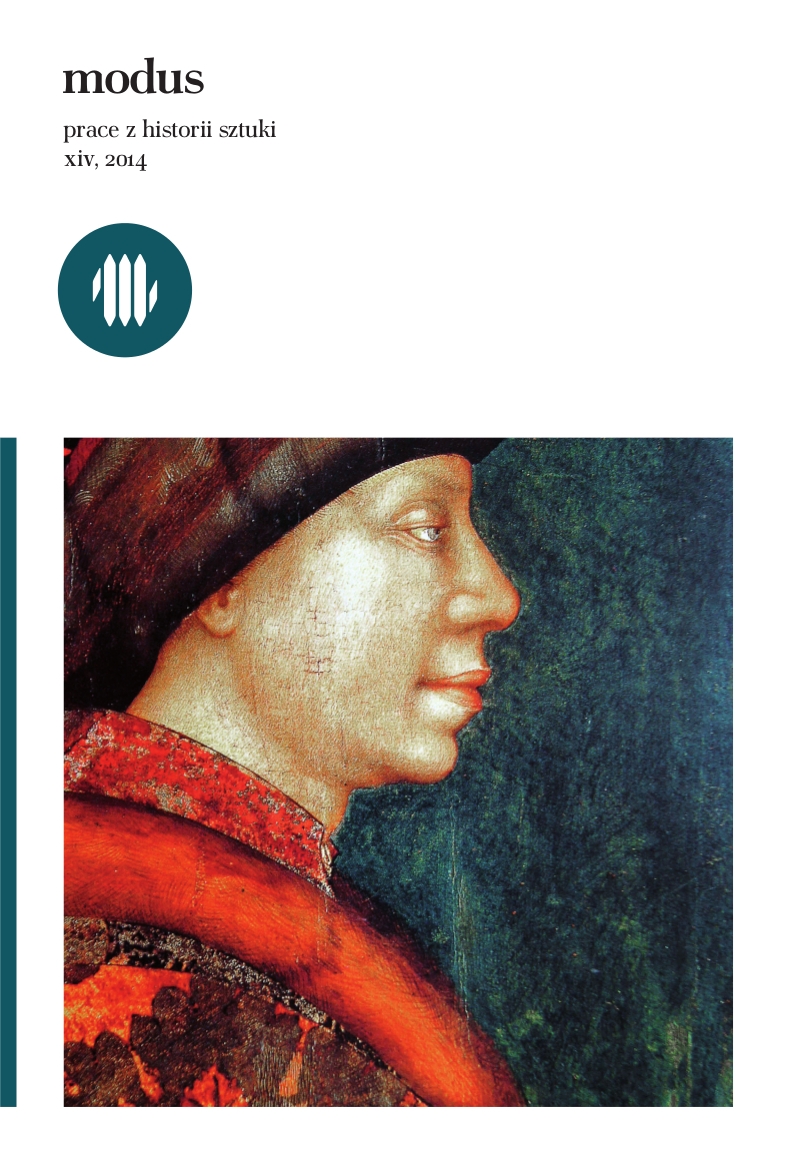

Fantasia i ritrarre. O początkach portretu w Lombardii około roku 1400

Fantasia and ritrarre. On the Beginnings of Portraiture in Lombardy around 1400

Author(s): Mateusz GrzędaSubject(s): Fine Arts / Performing Arts, Visual Arts, Sociology of Art

Published by: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego

Keywords: Fantasia; ritrarre; Portraiture; Lombardy art; 1400;paintings;

Summary/Abstract: The present paper investigates the beginnings of portraiture as an independentgenre of art. Contrary to the Vasarian tradition, which associates the beginnings ofportraiture with the birth of maniera moderna in Tuscany, the present author focuses hisparticular attention on two important centres of court art and culture, namely those ofPavia and Milan, which throve for the most part thanks to the patronage of the Viscontifamily. Thus the importance of Lombardy has been emphasised, as a place that had playeda significant role in the birth of portraiture in Italy at the turn of he fifteenth century.Written accounts found, among others, in the works of north-Italian humanists and artcollectors (e.g. Bartolomeo Fazio and Marcantonio Michiel) directly or indirectly testifyto the crucial role played by the artists associated with the court of the Viscontis in thedissemination of the new art genre, that is, of portraiture. In this regard, the names of threeartists: Giovannino de Grassi, Gentile da Fabriano and Michelino da Besozzo come to thefore, as of painters who enjoyed famę both in their lifetime and posthumously.Particular attention has been focused, however, on a text that originated outside themain humanist discourse, namely, on Cennino Cenninis treatise II Libro delTArte. It waswritten around 1400 by a Tuscan painter who, nonetheless, was well acąuainted with thereality of north-Italian courtly circles. The author of the treatise underscored that averefantasia e hoperazione di mano’ were two ąualities indispensable for practising the artof painting. The term fantasia seems to have here a similar meaning to that of the Latiningenium (mentioned, for example, by Theophilus Presbyter) or the Italian ingegno (whichlater occurred in the works of Vasari). Fantasia appears to be the artists main asset whichallows him to bring together the things observed in naturę according to his own liking.What is, however, equally important is the fact that nonę of the transformations done bymeans of the fantasia would have been possible without a preceding observation of naturę.It is in this very context that the word ritrarre, used by Cennini, should be interpreted. ForCennini this word meant not that much a simple copying of a thing perceived, but, rather,a process taking place in the artists memory. A painter who follows the ‘triumphal gate ofnaturę does not act automatically, but uses his intellect: first he assimilates, or, to put it inother words, memorises, a given thing, and only later does he re-create it on paper.Finally, the author goes on to demonstrate, on the basis of the analyses of selectedworks of art and written tradition, that the success of Giovannino de Grassi, Gentile daFabriano and Michelino da Besozzo in the courtly circles of Pavia and Milan, and lateralso in other parts of Italy, was due to a large degree to their skills in exhibiting the qualitythat Cennini had called fantasia, and to their ability to produce portraits, that is toimmortalise in the visual medium things observed

Journal: Modus. Prace z historii sztuki

- Issue Year: 2014

- Issue No: 14

- Page Range: 99-122

- Page Count: 24

- Language: Polish