Is God the Postmodern Stranger? Forms of the divine in Transgressive fiction

Is God the Postmodern Stranger? Forms of the divine in Transgressive fiction

Author(s): Ioana BetegSubject(s): Language and Literature Studies, Studies of Literature, Comparative Study of Literature

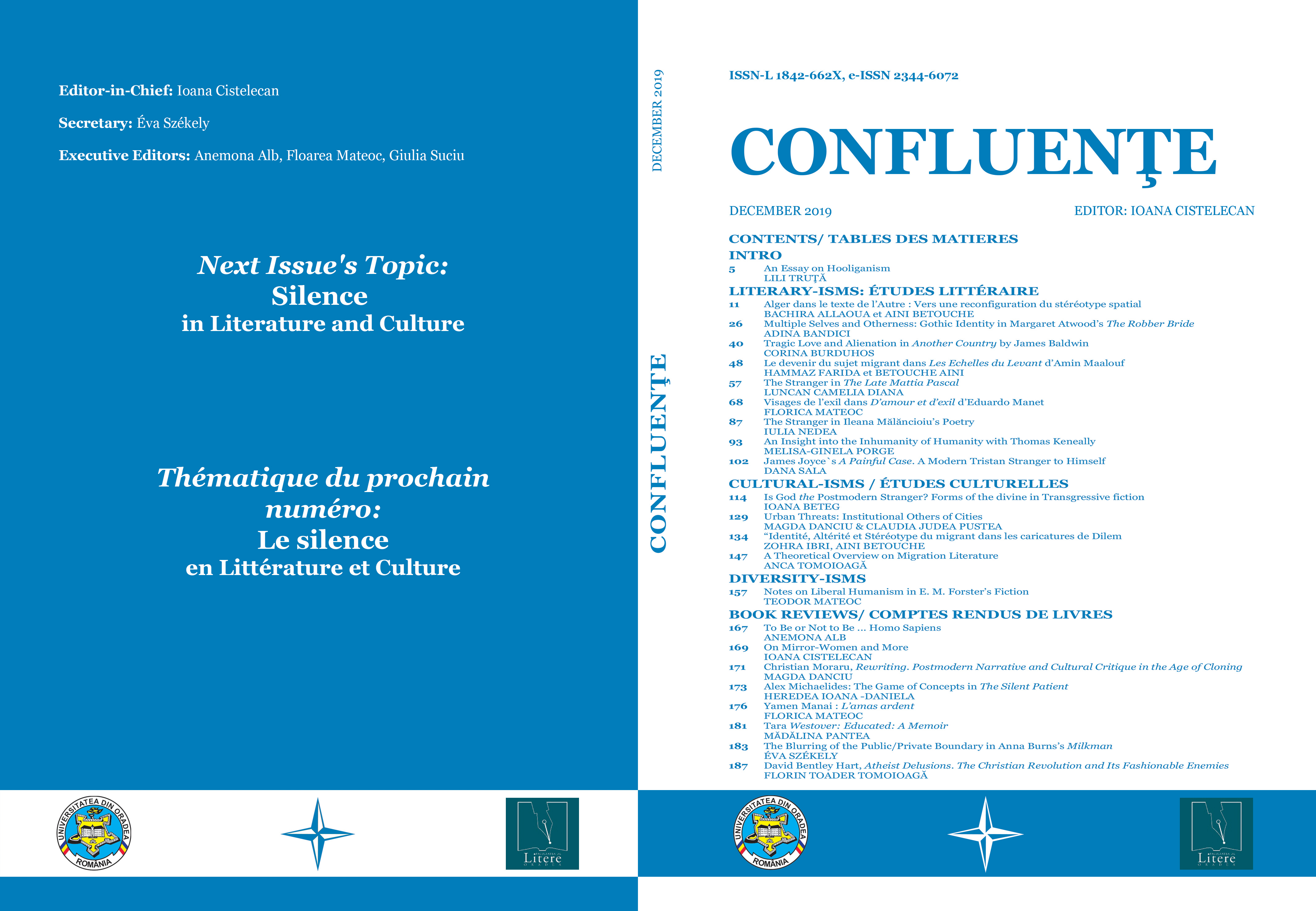

Published by: Editura Universitatii din Oradea

Keywords: alienation; dystopia; individual; Postmodernism; religion; stranger;

Summary/Abstract: Is God the Postmodern Stranger?Forms of the divine in Transgressive fictionIoana Beteg Abstract: God does exist in Postmodern fiction, in the most dangerous and unpredictable of worlds. There is God in mayhem, regardless of whether one believes it or not. What Postmodernism does to the image of divinity is interesting to unravel – Postmodern alienation takes numerous forms and follows unimaginable patterns; thus, the autopsy of religious instances is not to be avoided. God does not need to exist to punish people, as they are capable of punishing themselves and others. God is there, in many cases, to create social and religious ambiguity and to threaten the mischievous and misbehaving individuals. Do they punish each other? Do they take revenge? Collective identity, the identity that comes with believing in a set of rules and regulations imposed by the churches, by a newly imagined God, by books, could be more powerful than individual identity. Key words: alienation, dystopia, individual, Postmodernism, religion, strangerA Postmodern approach to religion – is God outworn? Is there any God in Postmodern fiction? If so, how does He help, influence, punish or redeem the rebellious, depressive, inquisitive, skeptical individuals that Postmodernism sits us down with? If He indeed exists, is He forgiving and merciful? Does the Postmodern man look at God as the only lifeboat in the torment of existence, or does he blame God for the Postmodern hazard? Moreover, a tormenting question that needs an answer is: is God replaceable in the Postmodern era? These are questions that we aim to answer in this paper; even though it is not (and it could not be) an exhaustive research on the issue of the divinity in Postmodern literature, it is an exploration into the way the reminiscence of God can influence and alter the unfolding of Postmodern narratives. Cat’s Cradle, Adjustment Day, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and Fight Club play with confinement and anxiety to the point of madness, but, as we are to find out, the dystopian nightmare would not be final without the inactions and passivity of a much-needed God. Postmodernism pushes the Modernist ideologies and thoughts one step forward, redefining and re-conceptualizing important pillars of literature such as individualism, identity, alienation and even consciousness. If Modernism brings to the surface a type of individual that is difficult to understand and is grounded in the reality of the times, Postmodernism challenges us to grasp and accept the miscellaneous human existence, unveiled and carefully autopsied. Does God see everything? Does God see and judge the Postmodern man? Is there a God to judge the Postmodern man? Kurt Vonnegut, in Cat’s Cradle, proves that God, or at least a divine figure, a divine figure of authority, is needed for the functional development and structure of the Postmodern world. He tells us that we do require a collective identity to look back to, to look forward to and to help us prioritize and morally and ethically organize our lives. Postmodernism coins the deconstruction of religious belief. Cat’s Cradle does not tell us about God, God’s worthiness, domination or control, it does not lecture us about the controlling power of the Bible or its followers and apprentices; Cat’s Cradle tells us about the way people perceive the teachings of a book and the way a certain limited society can fall prey to the written word. All it takes, in our case, is for the aforementioned book to have enough readers that contemplate, not necessarily believe, the sayings in the book. Vonnegut expands our understanding of control and mass manipulation, and, more importantly, of the sadistic manner the Postmodern man enjoys being subdued, while at the same time, ironically disobeying the rules. Irony veils the critical and satirical way in which the characters in Vonnegut’s novel are inspired, influenced, controlled and maneuvered by religion. We say religion, but we know that we do not have to mean God. God is the symbolic figure of religious belief, but religion does not have to translate into God. Religion can take numerous forms, it could be interpreted in different ways and using different lens of appreciation, and whether it exists in the real world or not remains a subject for debate. Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle brings forward a new form of worship, namely Bokononism. Is Bokononism real among us, the real readers of literature? We read about Bokononism in Vonnegut’s novel just as we read the Bible. Does that make Bokononism real? Does that make the Bible less reliable? These are questions that are to be answered after a thorough and detailed analysis of the way the Postmodern man talks to God, to the divinity, or curses, blames and tries to get rid of any divine authoritarian figures. Bokononism is popular on an island in the Caribbean, called San Lorenzo. What we need to understand about the practices and rituals on this imaginary island is that the people inhabiting it call themselves Christians and preach about Christianity to anyone that dares ask about their religion, but, as a subcultural religion, they practice Bokononism. The subculture, or the other-culture of the book of Bokonon is, at the surface of the society, regarded as punishable by death. We are forced to imagine a religion that everybody practices and is cultured about, but that, at the same time, is illegal. Bokononism attracts individuals that have lost sense of the spiritual world and whose only way to redeem themselves is through violence, or, if not violence, through a brutal punishment that is meant to alienate the individual from his original beliefs. More than this, Bokononism preaches a nihilistic perspective on life that is mingled with peaceful, eerie practices. Could this mean that the Postmodern man needs a divine existence to hold on to but that, at the same time, he needs to replace God? Is God outworn? Vonnegut’s 1963 novel and Palahniuk’s Adjustment Day, first published in 2018, seem to support this idea; more than fifty years of literature, culture and shifts in ideology and we circle back to the same idea, namely that God cannot keep up with Postmodernism. The first poem, the first calypso, that talks about Bokononism, more precisely, about Bokonon, the island’s preacher, does tackle the difference between bad or good, but it does so by emphasizing the necessity of both. Saussure’s structuralist theory brings forward the binary oppositions that exist in the structure of language, just as they exist in the Bokononist perspective on life: "Papa" Monzano, he's so very bad, But without bad "Papa" I would be so sad; Because without "Papa's" badness, Tell me, if you would, How could wicked old Bokonon Ever, ever look good?(Dynamic Tension, 2010: 47)It is important to understand here that Papa Monzano is the island’s most prominent political figure, a face that everybody on the island recognizes and obeys. According to Bokonon’s thinking, Papa is undoubtedly the symbol of evil, of sin and vice, whereas Bokonon represents exactly the opposite. Bokonon thinks of himself no more than he actually is, but he brings to the surface the idea that a greater evil on the island polishes or hides his mischievous nature. One needs a demon, a counterargument, a culprit. The islanders are in need of a powerful figure that is worse than they are, that could be pernicious to their beliefs and ideologies. Their lives are funded in the aforementioned binary opposition – good and evil – regardless of the fact that both good and evil are represented by earthly, human figures. The good is reliable, the good is real, the good is human. So is the evil. The concepts, the symbols, are depicted through some of the islanders’ peers, and, as a consequence, good and bad are rendered possible in the real world. The first calypso marks the transition from idealized, abstract concepts to real notions: Bokononism seems, as a religious belief, well-grounded and genuine. Similarly, the first teachings of the Talbott book in Adjustment Day read as follows: “Imagine there is no God. There is no Heaven or Hell. There is only your son and his son and his son, and the world you leave for them” (2018: 37). The black and blue book, the Talbott book, gives humans the ultimate power, the crucial and pivotal faculty: independence. It emphasizes the concept of free-will, if we dare say so, but not following the Christian understanding of free-will, where God enables its worshipers to act according to their system of beliefs and consequently, be judged for their actions. The Talbott book throws its followers into a world where actions do have consequences, but where one does not immediately suffer the repercussions of his actions – one’s descendants do. Both the book of Bokonon and the Talbott book play upon the idea that good and evil exist and that they guide people’s lives, but, at the same time, intertwine the existence of virtue, dignity, immorality and vice with reason, pragmatism and reality. Despite the fact that both religions are based on an ironic, satiric, critical but at the same time, idealized view on life, they both make reference to God – the real, biblical God. For instance, the Talbott book says that “God alone can create anything new. We can only recognize patterns, identify the unseen, and combine things to create slight variations” (2018: 198). God’s presence is a mere tool of comparison between the real and the unreal, for the Talbott book uses the idealized symbol of divinity in order to control and manipulate the large mass of people reading and following the teachings of the black and blue book. God is present in Talbott’s teachings for one single reason: to hold down, to calm down, to compose the readers’ actions. The book tries to teach its readers that races, sexual orientations, sexual preferences, ethnic backgrounds are important. Adjustment Day imagines a catastrophic world where races can mix only under certain circumstances, where sexual preferences decide your future and where slavery returns to torture and torment women. Adjustment Day comprises what should be a dystopian nightmare for today’s society (a society that claims to be lacking these types of racial, sexual or ethnic discrimination) and creates a world where heterosexual people are not allowed to racially mix, even living in different locations, and where homosexuals renounce their sexual freedom and are forced to live in a place called Gaytopia. Colors and sexual orientations rule Adjustment Day. The Postmodern man tries to unpuzzle his fragmented identity and live by the rules of a society that seems to have forgotten that there are any rules.Cat’s Cradle deconstructs the idea of Americanism and its presumed foundations, by stating that “American foreign policy should recognize hate rather than imagine love” (Why Americans are hated, 2010: 45). The mechanism that runs the American society is clearly flawed in the eyes of the Postmodern man, but what is there to do to fix it? Hate seems to be a viable solution, a working plan against a world driven by God’s principles and altered by humans. Hate, death and reason are the pillars of Bokononism and the Talbott book’s teachings: “May each man strive to be hated. Nothing turns a man into a monster faster than the need to be loved” (2018: 101). What about love? Love, the Christians would tell us, is one of God’s greatest gifts; the ability to love and be loved, given to all humans and animals alike, is what should drive us to be better each day. A mother’s love to her children, the parents’ love to each other, the children’s love to their parents, a man’s love to a woman and so on, no matter what type of love we choose to talk about, the understanding of the concept does not change. Even in a Postmodern, disrupted world, love ought to have a meaning. Love is rooted both in reason and imagination, both in the palpable and the unseen – love is part of sin. As Kierkegaard puts it, “sinfulness is by no means sensuousness, but without sin there is no sexuality, and without sexuality, there is no history” (2000: 138). Whether we refer to the theological understanding of sin (we ought to keep in mind that, according to the bible, the first sin happened in the Garden of Eden and it led to Adam and Eve’s exploring their sexuality) or to the Postmodern sinful man, sin is, on numerous occasions, closely related to sexuality. Sexuality and race divide Palahniuk’s characters, reason divides Vonnegut’s characters. Postmodern characters do not dare search their hearts and souls for love, accepting their sinful nature without inquiry. Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian follows the pattern of fragmentary relationships with the divine, a relationship that is bound to exist as a consequence of the Postmodern consciousness and identity; the novel brings into discussion the ways in which, dare we say again, risking redundancy, binary oppositions shape the Postmodern man’s thinking and actions. One of McCarthy’s characters, similar to characters in Adjustment Day or Cat’s Cradle, acknowledges the fact that reason stands behind free-will. One filters everything he experiences through thought and common sense:a man's at odds to know his mind cause his mind is aught he has to know it with. He can know his heart, but he don’t want to. Rightly so. Best not to look in there. It ain’t the heart of a creature that is bound in the way that God has set for it. You can find meanness in the least of creatures, but when God made man the devil was at his elbow. A creature that can do anything. Make a machine. And a machine to make the machine. And evil that can run itself a thousand years, no need to tend it” (2010: 17). Postmodern literature places God, the God that we all know about, both in the center of the society, in the center of our thinking and acting, and outside of it. The Postmodern individual writes the deconstruction of God, following closely what the Deconstruction taught him. God controls the Postmodern man, whether he acknowledges this or not. Even if one renounces God, and states so, he, in a way, subdues himself to the influence of the divinity over the world. The Postmodern man needs a religion, he needs a theory, a set of rules and ideas to ground his life on, for otherwise he would be swept away by the mischievous and hazardous dangers of life. Without a religion, no matter how funded in reality or imagination it might be, the Postmodern man would yield to self-destruction without a fight. We are not stating that God prevents the man from destruction or self-destruction, but rather that He helps man dwell in the illusion of a happy ending. The Postmodern man does talk about God, even if he does not talk to God. The Postmodern man invents a new God, a better God, a more real, dependable or approachable God, but he does not take God for granted. The Postmodern man sees God as a hard-to-approach but interesting stranger. The Postmodern individual circles around the idea of a divine, superior and more powerful figure that gradually takes control or, on the contrary, that is to gradually lose control over the Postmodern man’s destiny, but what is to be noted here is the individual’s need for someone to have more power than him. This, as we have already mentioned, means that we still have someone or something to blame for our actions, should they fail, but not thank, should they succeed. This is the Postmodern God’s job: to ideologically exist, to be present if our actions develop consequences beyond repair. Even the most absurd of worlds takes God as the center. Even a world dominated by carnal sexuality, raw types of behavior, drugs, alcohol and impoverished minds, as the one we read about in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, uses God as a safety net: “you’d better take care of me, Lord… because if you don’t you’re going to have me on your hands” (2005: 30). Our drugged, tipsy character blames God for his actions, more precisely for the consequences of his actions, saying that taking the Lord’s “gibberish seriously” is what got him in trouble (2005: 30). With a suitcase full of drugs and a lot of crimes staining their pasts, the two main characters, Raoul Duke and his attorney, dr. Gonzo, drive recklessly to and from Las Vegas, destroying one of the hotel rooms they are staying in and, consequently, destroying any chance they have at a normal life. They self-destruct their chance to freedom and peace, indulging in a life of hallucinations and imagination. They become the ones that talk gibberish, for their hallucinations worsen by the hour. When the miscellaneous imagination-hallucination-reality becomes unbearable and they feel there is no escape and the moment of their arrest is fast approaching, the only safe way to face the reality of their crimes is to talk to a priest. God’s sent on Earth, the priest, is the only one that could guarantee them peace of mind and freedom of the soul, for they say: “Jesus Creeping God! Is there a priest in this tavern? I want to confess! I’m a fucking sinner! Venal, mortal, carnal, major, minor – however you want to call it, Lord… I’m guilty” (2005: 30). The two do not try to deny their drug addiction, they, up to a point, take responsibility for what they are doing to their bodies and how their drug binge affects the ones around them. The novel even opens with the narrator, who is also the main character, describing both the location they are in and the state of mind they are in: “we were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold” (2005: 1). The novel starts with drugs and thus warns us of what is about to unfold. Addiction is by no means unfamiliar in Postmodern writings, but Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas takes addiction to the extreme. Duke and Gonzo are passing through the desert in order to get to Las Vegas, but the calm and quiet of the desert is rapidly shattered by the sound of their car going 100 miles per hour, by the screeching sound of the brakes and the violence and brutality of the characters’ lack of reaction. After being on the verge of suicide and manslaughter, Duke says to his attorney: “Never mind (…) It’s your turn to drive” (2005: 1). The atmosphere of the novel – writing, choice of words, pace – allows one to get a clear insight into the characters’ world, hallucinations and vivid dreams. The violence of the text fills in the void of any real action, for not much happens in the novel. Nonetheless, not the action is important here, but language and thought. We become mesmerized by the thoughts of Duke and Gonzo, for the actions are clearly predictable. Everyone knows no good can come out of drug use, and it is not hard to imagine what a suitcase full of drugs and a convertible with two stoned men equals, but it is harder to convey the stream of thoughts they experience in that state of mind. What we understand is that not even drugs can erase the idea of God. When drugs take control of your body and mind, you lose power over everything. Just as one puts his destiny in the hands of God and denies any responsibility for his actions after having done so, drugs allow you not to feel culpable for what you say or do, while under the influence. Thus, Duke makes it easier for us to understand his paranoia and asks us to understand his eerie behavior and sympathize with him, for he says: “my legs felt rubbery. I gripped the desk and sagged toward her as she held out the envelope, but I refused to accept it. The Woman’s face was changing: swelling, pulsing… horrible green jowls and fangs jutting out, the face of a Moray Eel!” (2005: 8). Numerous instances of visual imagery drag us into Duke and Gonzo’s world and influence us into empathizing with their obtrusive and degrading behavior. A world with no God requires one, screams deeply for any sort of divine intervention, whereas a world where God is everywhere, where God is imposed on people, where individuals are force-fed with God’s teachings, tries to dispose of God. Roth’s teenage character in Indignation revolts: “I do not need the sermons of professional moralists to tell me how I should act. I certainly don’t need any God to tell me how. I am altogether capable of leading a moral existence without crediting beliefs that are impossible to substantiate and beyond credulity, that, to my mind, are nothing more than fairy tales for children held by adults, and with no more foundation in fact than a belief in Santa Claus” (Under Morphine). Marcus is a self-proclaimed atheist, born and raised in a Jewish family, that, despite all odds, is required to attend forty hours of sermons in order to complete his studies. His rant, that we quoted earlier, comes after a long string of events that, nowadays, would not catch our attention. After moving dorms several times due to his roommates’ inappropriate behavior, the Dean asks Marcus into his office to clarify the situation. Marcus, as a reasonable and well-grounded individual, tries to explain to the Dean that the reason behind his decisions was the inability to study, sleep or relax in an environment that he cannot control. Marcus’ first roommate had the audacity to listen to music at night, when Marcus was trying to sleep, whereas the second roommate was impossible to communicate with. What Marcus does not want to admit is the fact that he thought he fell in love with one of the students in the campus, a student that seemed more than open to all of Marcus’ desires, and that the second roommate dared to challenge Marcus to face reality. While our main character and narrator thought that what he and the student felt was love, his roommate brought to his attention the fact that the girl has the tendency of treating all boys the same way she treated Marcus. One of Marcus’ long-lasting wishes was to lose his virginity before turning 19, and the girl seemed willing to help him in the matter. They have a brief sexual encounter in Marcus’ roommate’s car that rapidly turns into an obsession for our narrator. He cannot help but fall in love with the girl whose actions boosted his self-esteem and confidence. He is no longer the Jewish guy who gets straight A’s in school and also helps his parents at the kosher shop they own, he is now like all the rest. Her openness changed his status, but his relationship with God or any other religious figure remained unchanged. He is the same rebellious but quiet atheist that he was before, and he is not afraid to admit it. We have mentioned the fact that God does exist in Postmodern fiction, in the most dangerous and unpredictable of worlds. There is God in mayhem, regardless of whether one believes or not. There is God even in Palahniuk’s Fight Club, where the line between individualism and collective identity is so blurry that it transforms into multiple identity, where the world is ruled by chaos and wrong-doings and the only rules we get to read and understand are the rules of Fight Club, the underground community where everything is possible. Fight Club comes forward with a form of unity that founds itself on possibility, where lies do not matter, and the outside world is of little importance. The members of Fight Club are misfits, are common people that need a place of rest, of relaxation and nirvana, in the most ironic sense. The narrator, depressed, alone and isolated comes in contact with Tyler Durden, the embodiment of everything our narrator is not. Tyler Durden soon becomes the guide, therapist and best friend of our narrator; Tyler is masculine, charismatic, powerful, authoritarian and dominant, while the narrator lacks all traces of manliness and power. They decide to escape their boring, mundane lives and create Fight Club. In all mayhem, Tyler finds the time to discuss God, to write about God, saying that “If you’re male and you’re Christian and living in America, your father is your model for God. And if you never know your father, if your father bails out or dies – or is never at home, what do you believe about God? (…) What you have to consider, is the possibility that God doesn’t like you. Could be, God hates us. This is not the worst thing that can happen” (2007: 141).The image of God is palpable, is real, and, what is more, it is unique for each individual. The image of God is what you create of it, your God is yours only. We must take into consideration the following details about our narrator: he is an ordinary man working a more than common job, a man that has no desires, no aspirations, no goals or accomplishments. What is more, he has no name, or, at least, he does not disclose it. We know close to nothing about his past, his culture, his religion, his social background, so how are we to know about his God? One first question inciter is the fact that he is nameless – this could mean that he has no identity in the sense that he does not feel like he belongs to a certain group (he has no social, collective identity). Besides his suffering from insomnia and a sense of displacement, we are not given information on the narrator. Who is his God, if we know nothing about his father?The fact that he inquiries about the presence, existence and power of God (through Tyler) brings to mind the first calypso in Cat’s Cradle, where Papa Mozano talks about the binary good-bad structure. We have mentioned earlier that Fight Club blurs boundaries between identities, thus, not understanding the standpoint on the concept of God is reasonable. Our narrator does not know who he is, he is alienated from himself and from the world around him, and his imagination stirs up a fascination with brutality. Therefore, he does not know his God either. The feeling that God might hate him, as Tyler writes, comes from his inability to feel that he is an active part of the society and act accordingly. His only liaison with society was his apartment, where he developed a consumerist obsession with owning IKEA furniture (like the rest of his entourage), and, as a consequence, when his apartment burnt down in a ravaging fire, he lost not only that, but also his identity and sense of self. If he cannot identify himself as a regular individual that plays along with the rules, regulations and stereotypes of the American society, he is nothing. The fire burnt to the ground his identity, his inner self. He is not connected to God for, according to Tyler, he is not connected to his father. This paternal relationship one seemingly needs to have to God resembles Palahniuk’s vision in Adjustment Day, where paradise and hell lose any kind of meaning, and they lose their meaning to reality. One must live only for what he knows, disregarding the fact that his good deeds might be rewarded in the future (in Heaven), or his wrong-doings might be punished later in the afterlife. The fragmentation between the real and the fictional consequences of one’s actions ushers the disconnection between identity and imagination. Palahniuk’s characters envision a world where rules sarcastically pattern the society, and where you can effortlessly create a new society to fit your desires. Fight Club’s narrator creates his mayhem where people literally beat the mundane out of each other and where the most important rule is never to talk about their enclosed community, while Adjustment Day threatens and, at the same time, entertains people with the list: a list accessible to all people that is said to decide the fate of humanity. One can submit a name to the list and depending on the number of votes the name receives in a span of time, the said person is to be murdered. The list gives everybody God-like power, it gives everybody the faculty and competence to decide whether his or her peer is to die or not. What is to come of a religious dystopia? How is it to end? Postmodernism faces us with the unstable relationship between common sense and religious teachings, between reason and childish credulity and between pragmatism and indolence. The fight between collective identity and individualism is unjust and violence will always find its place in this battle. Cat’s Cradle provides us with a vivid and desolate picture of what the world – a world ruled and looked over by God – is bound to look like in the future:Someday, someday, this crazy world will have to end, And our God will take things back that He to us did lend. And if, on that sad day, you want to scold our God, Why go right ahead and scold Him. He'll just smile and nod.(Mona thanks me, 119)Grim, dull, apocalyptic and empty is the end of the world, as Vonnegut coins it. Everything we have and everything we are is only borrowed from God. He, thus, has the power to take our everything back whenever he decides to do so, and there is no fighting back. The Postmodern apocalypse is, according to Bokononism, not necessarily violent and brutal, people do not grasp their last belongings and start running around chaotically, there is no survival and hope like in McCarthy’s The Road, there is no train track leading to a zone that dwells the last remains of life and the mystery of unidentified phenomena, as in Roadside picnic signed by the Strugatsky brothers, and there is not even the promise of a better, calmer, quieter afterlife. There is only a mean God, a shrewd God that takes away everything. What Bokonon, the father figure, the embodiment of power and the ultimate leader, is sure of is that, in the end: “In any case, there's bound to be much crying. But the oubliette alone will let you think while dying”(The Iron Maiden and the Oubliette 118)In the end, reason and judgement fail you last. The apocalypse takes everything away from you but reason. This is the liaison between the Postmodern apocalyptic worlds we have mentioned: reason, grounds, rationale. You witness your destruction consciously: the narrator in Fight Club watches his apartment burning down and trembles with anxiety, just as one can easily connect to the internet and read his name on the list in Adjustment Day and is utterly powerless and incapable of erasing his name from the list and as Raoul Duke’s brief hallucinations are purposefully nourished with drugs in order to escape reality and indulge in chaos. They are all aware of their upcoming demise, they are all thinking while dying. A Postmodern world where God is hand-made, where God is thought and created by the people, why are they pushed to commit the ultimate act of power over their bodies? Suicide is the last statement one can make with regards to their individuality, to their identity and to their exerting control over their bodies. Suicide is the most personal decision one could make. But the road to it must be filled with insecurity and unhappiness, with feelings of alienation and self-doubt – this, or one must feel threatened. Our Postmodern aliens are all threatened by something bigger than them, by something more destructive and powerful than they could ever be. Adjustment Day tries to convince us that “suicide is the ultimate act of consumption” (2018: 296). Hopelessly awaiting for Adjustment Day, the day when everything is bound to change irredeemably, only through suicide you can prove your self-worth. It is only through suicide that you can consume yourself before the havoc of the world swallows your identity. While Adjustment Day pushes people towards suicide, Fight Club does not conceptualize the act so much, for it goes through with it. On the other hand, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas builds up the expectations for an upcoming disaster, be it a suicide or a sudden death (maybe caused by drug overuse, maybe a car accident), but fails to meet the readers’ expectations. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas mingles hallucination with reality but allows the readers to clearly distinguish between the two – Fight Club only gives us the key to deciphering reality from imagination in the end. Cat’s Cradle dramatic ending gives us the illusion that suicide is the only escape route from the rapidly solidifying world. The threat in Vonnegut’s novel is a chemical substance that, fallen in the wrong hands, could destroy the world. The material is said to solidify every liquid it comes in contact with, from water to mud to blood. Thus, the substance, ice-nine, could be used by the army troops when walking through unstable mud or dirt, or it could be used to murder whoever one wants. From this point of view, it functions just like the list in Adjustment Day. Nevertheless, while the list in Palahniuk’s novel does not incite people to be pragmatic and reasonable, allowing everybody to submit names and to vote, deciding other people’s destiny, the Book of Bokonon teaches its believers to search for answers, to be inquisitive and intrigued: Tiger got to hunt, Bird got to fly; Man got to sit and wonder, "Why, why, why?" Tiger got to sleep, Bird got to land; Man got to tell himself he understand.(A White Bride for the Son of a Pullman Porter, 2010: 81)The Postmodern individual dies a painless death, be it caused by mysterious chemical substances, a bullet to the head or drug overdose. To answer the questions we began with, we dare say that God (to use the generic term) is an active, robust and complex character in Postmodern fiction that has no intention to save the other characters from self-destruction. God, as we have already mentioned, acts as a lifeboat when life starts to derail, he is a secondary actor in the miscellaneous Postmodernist play. If one cannot find God, one creates it. When one feels bombarded with God’s teachings, one rebels and loses everything over pride and the love for insurrection. When one finds his relationship with God distant enough and comfortable enough, one starts losing faith. God, an alien, a stranger, is interesting in fiction only if he poses a challenge or a threat to the individual’s freedom, free will, or mental stability. References:BLOOM, Allan. The Closing of the American Mind: How Higher Education Has Failed Democracy and Impoverished Todays Students. Simon & Schuster, 1993.BLOOM, Harold. Philip Roth. Chelsea House Publishers, 2003.BLOOM, Harold. The Western Canon: the Books and School of the Ages. Papermac, 1995.CALLERO, Peter L. The Myth of Individualism: How Social Forces Shape Our Lives. Rowman & Littlefield, 2009.EAGLETON, Terry. The Illusions of Postmodernism. Blackwell Publishers, 1996.ELLISON, Ralph. “What America Would Be like without Blacks.” Time, 6 Apr. 1970.FINKIELKRAUT, Alain. Lidentité Malheureuse. Gallimard, 2016.FITZGERALD, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby. Penguin Books, 2013.GRAYSON, Erik M., and Edward Kemp, editors. “The Fiction of Self-Destruction.” Stirrings Still. The International Journal of Existential Literature, vol. 2, no. 2, 2005, www.stirrings-still.org.HEMINGWAY, Ernest. The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway: the Finca Vigia Edition. Scribner, 2007.HEMINGWAY, Ernest. The Old Man and the Sea. Heritage Publishers, 2007.HONG, Howard Vincent, and Edna Hatlestad Hong. The Essential Kierkegaard. Princeton University Press, 2000.JAEGGI, Rahel, and Frederick Neuhouser. Alienation. Columbia University Press, 2016.“Judaism: The Oral Law -Talmud & Mishna.” Suleyman, www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-oral-law-talmud-and-mishna.“King James Bible.” King James Bible Online, www.kingjamesbibleonline.org/.THOMPSON, Hunter S., and Ralph Steadman. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas a Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream. HarperCollins, 2005.MASON, Fran. Historical Dictionary of Postmodernist Literature and Theater. Rowman Et Littlefield, 2017.McCARTHY, Cormac. Blood Meridian, or, the Evening Redness in the West. Vintage International, 2010.McCARTHY, Cormac. The road. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007.McHALE, Brian. Postmodernist Fiction. Routledge, 2003.NABOKOV, Vladimir. Lolita. Random House, 1998.PALAHNIUK, Chuck. Fight Club. Vintage Books, 2007.PALAHNIUK, Chuck. Adjustment Day. W W Norton & Co Inc, 2018.ROTH, Philip. Portnoy's Complaint. Vintage Books, 1994.Roth, Philip. “Indignation.” Fantastic Fiction, www.fantasticfiction.com/r/philip-roth/indignation.htm.ROTH, Philip. Goodbye, Columbus and Five Short Stories. Houghton Mifflin, 1989.SAFRAI, Shmuel, and Peter J. Tomson. The Literature of the Sages. Midrash and Targum, Liturgy, Poetry, Mysticism, Contracts, Inscriptions, Ancient Science, and the Languages of Rabbinic Literature. 2006.SALINGER, J. D. The Catcher in the Rye: a Novel. Little, Brown and Company, 2014.SARTRE, Jean-Paul. Existentialism and Humanism. Translated by Philip Mairet, Methuen&Co, 1966.SCHWARTZ, Barry. The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less. HarperCollins, 2009.SKINNER, B. F. Science and Human Behavior. Free Press, 1965.STRUGATSKY, A, B. Roadside Picnic. London: Gollancz, 2012THOMPSON, Hunter S., and Ralph Steadman. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas a Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream. HarperCollins, 2005.VONNEGUT, Kurt. Cat's Cradle. Dial Press Trade Pbks., 2010.WATT, Ian. Myths of Modern Individualism: Faust, Don Quixote, Don Juan, Robinson Crusoe. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Journal: Confluenţe. Texts and Contexts Reloaded

- Issue Year: 1/2019

- Issue No: 1

- Page Range: 116-130

- Page Count: 15

- Language: English