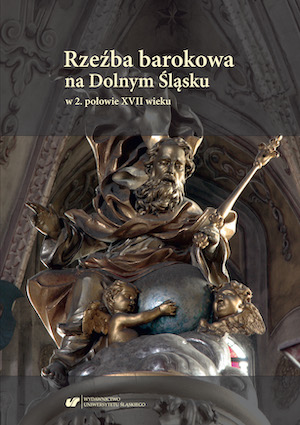

Rzeźba barokowa na Dolnym Śląsku w 2. połowie XVII wieku

Baroque sculpture in Lower Silesia in the second half of the 17th century

Contributor(s): Artur Kolbiarz (Editor)

Subject(s): Fine Arts / Performing Arts, Architecture, Visual Arts, History of Art

Published by: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego

Keywords: baroque sculpture; small architecture; modern art; Silesian art; Central European art; Lower Silesia; Kingdom of Bohemia; Habsburg Monarchy

Summary/Abstract: Zamieszczone w niniejszym tomie materiały stanowią pokłosie sesji naukowej: "Rzeźba na Śląsku w 2. połowie XVII w." zorganizowanej 20.01.2017. w Muzeum Miedzi w Legnicy. Przedsięwzięcie to miało szczególny charakter, bowiem rzeźba barokowa - potraktowana jako temat przewodni - rzadko staje się obiektem zainteresowań badawczych. Niniejsza książka nie pretenduje do prezentacji kompleksowych dziejów rzeźby na Śląsku na przestrzeni 2. połowy XVII w. Omawiane przez autorów zagadnienia dotyczą jednak obiektów, artystów, lub problemów pomijanych do tej pory, bądź słabo rozpoznanych, w istotnym stopniu uzupełniając i korygując stan badań, zawarty przede wszystkim w w wydanej przed ponad trzema dekadami syntezie rzeźby barokowej na Śląsku pióra prof. Konstantego Kalinowskiego.

Śląsk - który w tym czasie wchodził w skład Monarchii Habsburskiej - pomimo peryferyjnego położenia względem Wiednia oraz Pragi poszczycić się może zabytkami rzeźby stojącymi na wysokim poziomie wykonania, łączącymi różnorodne inspiracje. Oprócz związków artystycznych z Czechami oraz Austrią działali tu również rzeźbiarze pochodzący, bądź posługujący się formami charakterystycznymi dla rzeźby południowoniemieckiej, morawskiej, flamandzkiej, czy francuskiej, czego owocem jest bogata mozaika artystyczna o szerokim spektrum stylowym. Znalazło się w niej miejsce dla nurtów klasycyzujących oraz dzieł antyklasycznych, w tym tzw. śląskiej maniery barokowej, silnie eksponującej walory ekspresyjne i zrośniętej z miejscową tradycją sztuki. Zjawiska artystyczne zapoczątkowane w rzeźbie śląskiej pomiędzy 1650, a 1700 r. miały swoją wspaniałą kulminację w 1. połowie XVIII w. Dokładniejsze rozpoznanie rzeźby siedemnastowiecznej - czemu służy także i ta publikacja - pozwala pełniej nakreślić kontekst dla erupcji ilościowej oraz jakościowej rzeźby, jakie miały miejsce na Śląsku około 1700 r.

- E-ISBN-13: 978-83-226-3679-4

- Page Count: 166

- Publication Year: 2020

- Language: Polish

Rzeźba legnicka około 1650 roku

Rzeźba legnicka około 1650 roku

(Legnica sculpture around 1650)

- Author(s):Aleksandra Bek-Koreń

- Language:Polish

- Subject(s):Fine Arts / Performing Arts, Visual Arts, History of Art

- Page Range:11-27

- No. of Pages:18

- Summary/Abstract:Research into modern sculpture made in Legnica’s art circles has been considerably intensified. A lot of new findings have emerged with regard to Renaissance and Mannerist sculpture. Researchers have also focused on early Baroque sculptures from Legnica. That is why the fact that the oeuvre of this milieu of around 1650 has barely been explored is all the more evident. Nevertheless, despite the tragic consequences of the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), interesting works were still produced at the time in Legnica and, especially, its environs. Sculptures produced in Legnica around 1650 were influenced by the oeuvre of sculptors active in the area in the first quarter of the 17th century. They influenced, for example the sculptor known as the Master of the Epitaph of Caspar von Stosch in Czernina. For example, after 1643 he made the epitaph of Michael Eichorn, which as late as in 1893 was still to be found in the Church of SS . Peter and Paul. Archive documents give us the names of artists active in Legnica around the mid–17th century, whom we have not managed to link to known works, artists like Johannis Knaute. The sculptor came from Freiberg and worked in Legnica from around 1615 until 1644. At the same time, there are works whose attribution is impossible. They include the monumental tombstone of the Sighofer family in one of the chapels of the Legnica cathedral. The tombstone was made between 1651 and 1655, most likely having been funded by Eva née Schweinichen, second wife of Johann Sighofer, imperial oficer and counsellor to the Duke of Legnica. We know of no other works by Legnica sculptors from that period, in which the form would be so unequivocally monumentalised. However, there are analogies for the way a majority of other elements were made in earlier sculptures from Legnica. Another characteristic of artists active in Legnica around 1650 is their reliance on tried and tested forms despite evident stylistic changes already happening at the time. The sculptor who undoubtedly replicated set patterns was Abraham Lewe working in the area until 7 November 1663. The mid-1670s was a time of important transformations happening in the wake of the sudden death of Duke George William in 1675. The remains of the last Piast duke were placed in the Piast Mausoleum in Legnica, built in 1677–1679. Its carved decorations were entrusted to the Viennese sculptor Matthias Rauchmiller, a renowned Baroque artist.

Epitafium burmistrza Martina Schmidta z kościoła św. Mikołaja w Brzegu – zapomniany przykład snycerki śląskiej 2. połowy XVII wieku

Epitafium burmistrza Martina Schmidta z kościoła św. Mikołaja w Brzegu – zapomniany przykład snycerki śląskiej 2. połowy XVII wieku

(The epitaph of Mayor Martin Schmidt from the Church of St. Nicholas in Brzeg – a forgotten example of Silesian woodcarving of the second half of the 17th century)

- Author(s):Romuald Nowak

- Language:Polish

- Subject(s):Fine Arts / Performing Arts, Visual Arts, History of Art

- Page Range:29-39

- No. of Pages:12

- Summary/Abstract:The wooden epitaph of the Mayor of Brzeg Martin Schmidt (1583–1668) was initially, i.e. in 1668, placed above the so-called parish priest stalls on the wall of the southern nave of the Church of St. Nicholas in Brzeg, to the left of the entrance to the vestry, next to another monumental epitaph of the family of deacon Daniel Kartscher (d. 1685). During a fire in February 1945 it probably burned down together with the rest of the furnishings. Fortunately, a very good quality photograph has survived, enabling us to analyse the work. The epitaph commemorated one of the most distinguished mayors in the history of Brzeg, a man who remained in his office for 45 years. It had a three-part architectural structure, which drew on the traditional form of late Renaissance epitaphs of burghers. The central part was an oval plaque with a Latin inscription referring to the deceased and his wife Barbara Runtzkin. It was flanked by two Corinthian columns, next to which there stood personifications of the cardinal virtues of Justice and Prudence. The epitaph was crowned with a broken volute cornice. In its centre, there was a low relief coat of arms of the Schmidt family and above it on a base – a tondo with a bust of the deceased painted on metal. The lower part of the work was a suspended cartouche in the form of a frame formed by an auricular ornament complemented by bunches of flowers and fruit, flanked by two atlas putti. It was filled with an emblematic picture painted on wood and stressing the need to remain vigilant in life to ensure constant Divine protection. The author of such a programme was probably Martin Schmidt himself. He was a well-educated man and a friend of many professors from the Brzeg Gymnasium Illustrae. Being on good terms with people at the court of George III of Legnica and Brzeg, he was probably in touch with the artists working there – the author of the portrait as well as the marine representation in the cartouche was Ezechiel Paritius (1622–1688), from 1662 a court painter to Dukes of Legnica and Brzeg. It is more difficult to identify the author of the early Baroque carved framing of the epitaph. However, if the founder used the services an eminent local artist associated with the court of the Legnica–Brzeg Piast dukes in the making of the painted part of the epitaph, he must have done the same when commissioning its carved decorations. The only artist who could make carved decorations of the epitaph of Martin Schmidt in Brzeg at the time was the Bohemian-born sculptor Lucas Müller (ca 1620–1689). As the co-author of the sarcophagus of Duke George III he must have been regarded as worthy of making an epitaph for Schmidt together with the court painter Paritius. This may have been the work that earned him the rights of the city of Brzeg he was granted in the same year in which Mayor Schmidt died.

Georg Zeller (około 1638–1716) i środowisko artystyczne w którym tworzył w świetle ksiąg metrykalnych

Georg Zeller (około 1638–1716) i środowisko artystyczne w którym tworzył w świetle ksiąg metrykalnych

(Georg Zeller (ca 1638–1716) and the artistic milieu in which he worked in the light of parish registers)

- Author(s):Artur Kolbiarz

- Language:Polish

- Subject(s):Fine Arts / Performing Arts, Visual Arts, History of Art

- Page Range:41-57

- No. of Pages:18

- Summary/Abstract:Georg Zeller is an artist known to scholars studying early modern sculpture in Silesia, but information about him does not go beyond the early period in his work. What can help to fill the existing gaps and introduce some order into the current information chaos are records from the Wrocław birth, marriage and death registers. Among the names of the sculptor given in the literature – Georg, Franz, Joseph – only the first one is correct. Zeller was born in 1638 in the Bavarian city of Ansbach. He settled in Wrocław shortly after finishing his professional education, around 1662, and initially worked for the Norbertine Monastery. As a consequence of this collaboration, he belonged to the Parish of St. Vincent. There, in 1667, he married Dorotha Knockner and baptised his sons: Sixtus (1668) and Johann Caspar (1670). Around mid-1673 he moved to the neighbouring Parish of St. Matthias, run by the Knights of the Cross with the Red Star, and settled near the auxiliary Church of St. Agnes. The year 1673 was marked by the baptism of his daughter Anna Rosina, who in 1701 married the sculptor Johann Frörix, and 1707 – by the death of Dorotha. In 1709 the widower married Maria Scholtze from Kąty Wrocławskie. Two years later the couple had a son, Franz Anton. The old artist died in 1716. Both monasteries, together with the Jesuits and the Poor Clares, made up the biggest Catholic enclave in predominantly Lutheran Wrocław. Around 1700 similar enclaves functioned in the southern (Parishes of St. Dorotha and Corpus Christi), eastern (Dominican Monastery) and south-western part of the city (Reformanti Franciscan Monastery). These locations were attractive to artists because of the ongoing Baroquisation and construction of churches, as is evidenced by the presence of numerous sculptors making up the core of Wrocław’s artistic milieu of Catholic denomination. Throughout his life in Wrocław Zeller may have functioned as a non-guild artisan, taking advantage of a monastery artist’s immunity. He often collaborated with numerous artists employed by the monks: carpenters, painters and sculptors, working on both monastic commissions and those outside monastic patronage, which he took on increasingly as time went by. He was one of those artists who carefully watched their competitors, modifying the formal language of his works. Combining his own, traditional education with solutions he observed in the work of younger artists, he adopted forms characteristic of mature Baroque art, as a result of which he was able to stay on the market for as long as five decades.

Ołtarz św. Marii Magdaleny w kolegiacie głogowskiej – historia i próba rekonstrukcji

Ołtarz św. Marii Magdaleny w kolegiacie głogowskiej – historia i próba rekonstrukcji

(The altar of St. Mary Magdalene in the Głogów Collegiate Church – its history and an attempt at reconstruction)

- Author(s):Dariusz Galewski, Jakub Szajt

- Language:Polish

- Subject(s):Fine Arts / Performing Arts, Visual Arts, History of Art

- Page Range:59-69

- No. of Pages:12

- Summary/Abstract:The altar of St. Mary Magdalene was funded by the Głogów canon Gottfried Jakob Urban Schönborn around 1697, as is suggested by the text of an ecclesiastical visitation document. It was located in the Collegiate Chapel of St. Mary Magdalene until 1945, when it was destroyed during the war. Its surviving elements were placed in the church after the war, encouraging attempts to reconstruct the work, using its existing remains. The altar was made of grey Silesian marble from Przeworno and white marble, probably from Supíkovice. Below the altar stone was a socle with an oval cartouche, flanked by two pedestals on which stood statues of James the Elder and St. Urban the pope. Between them a rectangular framework with a semicircular ending held a low relief depicting penitent Mary Magdalene kneeling at the entrance to a grotto, holding a cross in her right hand and leaning her left hand on a skull. The composition was framed by volutes with protruding acanthus leaves on which sat putto figures holding the founder’s coat of arms; above there was a sculpture representing St. Godfrey of Cappenberg. A cartouche placed before the altar stone held an inscription commemorating the founder. The iconography of the reredos highlighted the idea of conversion and penitence, as is evidenced by the representation of Mary Magdalene, who placed all her hopes for absolution of her sins in the cross. What was also important was her special role of intercession expressed in the cartouche. The form of the altar is without architectural elements, which in the late 17th and early 18th century was rare in Silesia. The Głogów reredos can be compared only to the 1694 altar of the Holy Family in the Chapel of St. Ivo and Holy Family in the Church of Our Lady on the Sand Island in Wrocław. The author of the Głogów piece is not known – he may have been a member of the workshop or collaborator of another sculptor who came, hypothetically, from the Southern Netherlands, and made the pulpit in the Collegiate Church according to models characteristic of Flanders.

Tu es Petrus… Ambona z kolegiaty w Głogowie. Jej dzieje, ikonografia i geneza artystyczna

Tu es Petrus… Ambona z kolegiaty w Głogowie. Jej dzieje, ikonografia i geneza artystyczna

(Tu est Petrus… The pulpit from the Collegiate Church in Głogów. Its history, iconography and artistic origins)

- Author(s):Jacek Witkowski, Jakub Szajt

- Language:Polish

- Subject(s):Fine Arts / Performing Arts, Visual Arts, History of Art

- Page Range:71-91

- No. of Pages:22

- Summary/Abstract:The pulpit from the Collegiate Church of the Virgin Mary was funded in 1697, where it was to be found until 1945, when it was seriously damaged during the war. Its surviving elements are on display today in the Collegiate Church and the local museum. The pulpit has not been studied extensively despite its high artistic value – the first man to note its visual qualities was an anonymous author of a visitation document drawn up between 1706 and 1711. The pulpit was made of white marble from Supíkovice and grey marble from Przeworno as well as white painted wood. Grey marble was used to make structural elements and some decorations. Its ideological concept can be found in an inscription placed on the backrest and quoting Christ’s words addressed to St. Peter (Matthew 16:18): “You are Peter (Rock) and on this rock I will build my Church.” The words became the theological and legal basis of the primacy of St. Peter and his papal successors in the universal Church. This was splendidly expressed by the sculptor of the Głogów pulpit, showing Peter as a high priest wearing an ancient-style garments – a tunic and a loose toga. The front of the pulpit featured an expressive carved scene of the Conversion of St. Paul. It conforms to the iconographic tradition, well-established since the Middle Ages and based on an account of the event to be found in the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 9:3-6). Over the lintel with the date of the foundation, there was placed a double cartouche with the coats of arms of the founders of the pulpit. An oval relief with the Annunciation scene was a reference to the Marian dedication of the Collegiate Church in Głogów. The adjacent medallion is filled with the coat of arms of a cleric from the Silesian family of von Lohr, who may have contributed to the foundation of the pulpit. The whole was crowned with a carved wooden group representing Christ surrounded by radiant glory and angels. The Głogów pulpit is the second known Catholic pulpit in Silesia with a figural support. Despite some references to the Silesian tradition, in its artistic and formal origins it is primarily Netherlandish, more specifically Flemish. What is typical of Netherlandising art is the very material – dark marble in the structural parts and contrasting white marble in the figural decorations. Like in their Netherlandish counterparts, the Głogów artists used local stone deposits. Such double colouring of marble is very characteristic of stone sculptures of the Baroque era in Belgium and Holland, where its tradition goes back to Gothic art. Thus the work may have been created by a Flemish artist or a sculptor well familiar with Flemish models – at the current state of research his name is still unknown, as is that of the main founder of the pulpit.

Lubiąż i Świdnica – dwie koncepcje barokizacji śląskich wnętrz sakralnych w 2. połowie XVII wieku

Lubiąż i Świdnica – dwie koncepcje barokizacji śląskich wnętrz sakralnych w 2. połowie XVII wieku

(Lubiąż and Świdnica – two concepts of baroquisation of Silesian church interiors in the second half of the 17th century)

- Author(s):Paweł Migasiewicz

- Language:Polish

- Subject(s):Fine Arts / Performing Arts, Visual Arts, History of Art

- Page Range:93-107

- No. of Pages:16

- Summary/Abstract:Among the examples of baroquisation of church interiors in Silesia carried out or at least begun in the second half of the 17th century two stand out: the Cistercian Church in Lubiąż and the Jesuit Church in Świdnica. What they have in common is not just substantial scale, high artistic quality and use of numerous solutions previously unknown in Silesia, but, above all, French inspirations, which were rare in Habsburg lands in the 17th century and which reached Silesia via different routes. The furnishings of the Lubiąż church, preserved on site until the Second World War, was made in several stages, from the end of the tenure of Abbot Arnold Freiberger (1636–1672), through, largely, the tenure of Abbot Johannes Reich (1672–1691) and his successors in the 1690s and at the beginning of the following century. Initially, the main artist in charge of the project was Matthäus Knote, followed by Matthias Steinl – a designer and head of the workshop that produced most of the furnishings. Despite many novel solutions making the Lubiąż furnishings original and in some elements even “avant-garde” in stylistic terms, the very concept of baroquisation of the Lubiąż church is, as a whole, traditional. Although the furnishings do make up a regular, symmetrical composition, each of these “pieces of furniture” is an autonomous unit. By comparison, the other baroquisation, in the Jesuit Church, appears unique. It was carried out according to a design by the order’s sculptor Johann Riedel, who reached France during his study travel and learned many solutions used in that country. He came up with a concept according to which uniform furnishings for a vast majority of the interior were made in the 1690s and the first two decades of the following century. Unlike those of Lubiąż, the Świdnica furnishings draw on groundbreaking French solutions, which Riedel got to know in person, of the so-called décor extensif – with the main altar being linked to side altars by means of panelling, making up an extensive structure encompassing and organising the interior and giving it a Baroque character. This novel solution in Central Europe remained the only one of its kind in Silesia and was not imitated.

Marmury dolnośląskie. Zarys dziejów wydobycia i artystycznego wykorzystania w kamieniarstwie i rzeźbie w epoce nowożytnej na Śląsku i w Rzeczypospolitej

Marmury dolnośląskie. Zarys dziejów wydobycia i artystycznego wykorzystania w kamieniarstwie i rzeźbie w epoce nowożytnej na Śląsku i w Rzeczypospolitej

(Lower Silesian marble. A history of quarrying and artistic use in stonework and sculpture of the modern era in Silesia and Poland)

- Author(s):Michał Wardzyński

- Language:Polish

- Subject(s):Fine Arts / Performing Arts, Visual Arts, History of Art

- Page Range:109-138

- No. of Pages:31

- Summary/Abstract:The most important deposits of hard metamorphic rock from Upper Proterozoic (1 billion–635 million years ago) – whiteish and greyish veined marble with various degrees of graphite (less often biotite) – can be found in Lower Silesia near Konradów Wielki (Gross Kuntzendorf) and Supíkovice (Saubsdorf) in the Jesenik District as well as Przeworno (Prieborn) near Strzelin. From the early 13th century these villages belonged to the Bishops of Wrocław’s Duchy of Grodków and Nysa. The marble began to be quarried and used for artistic purposes as early as the turn of the 14th century, but the height of its popularity came only in the second half of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, when it became, alongside the local varieties of sandstone, the basic material used in sculpture and stonework in Nysa and from the last quarter of the 17th century – in Wrocław and, more broadly, Lower Silesia. After 1700 it was also exported to the neighbouring Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, e.g. its central province of Wielkopolska with the city of Poznań, and the Upper Silesia-Małopolska borderland with Jasna Góra near Częstochowa. Around 600 woks made of the marble in question have survived to this day. The whiteish-grey combination of marble, strikingly similar to the tandem of such rocks from Carrara (varieties of marmo bianco di Carrara and Bardiglio in figural, ornamental and architectural elements respectively) used in Tuscany, and in the Spanish Netherlands and Holland (Noir Belge and Noir de Dinant limestone with Carrara marble, alabaster or Cretaceous limestone from Avesnes-le-Sec according to an identical pattern) became a characteristic of the oeuvres of the most important masters of mature and late Silesian Baroque and Rococo styles: Sulpicius Gode, Johann Adam Karinger, Johann Albrecht Siegwitz and Franz Joseph Mangoldt. Direct models to be followed were provided in Wrocław by imported decorations of the cathedral Chapel of St. Elisabeth and the Electoral Chapel, in which the main material for figural sculptures was marble from Carrara (Domenico Guidi and Ercole Ferrata, from 1700) and Laas / Lasa in Tirol (Ferdinand Maximilian Brokoff, 1721–1722). In the most prestigious figural works the medium grained rock from Kondradów and Supíkovice was replaced with Thuringian alabaster or stucco, or even white painted limewood, which made it possible to achieve more intricate effects in sculptures. This unique regional material tradition continued beyond 1800.