This paper considers the data on the military, civil and ecclesiastical organisation, which Byzantium set up in the Balkans after 1018/1019. It presents the view that the development of military and ecclesiastical organisation can be followed in satisfactory continuity and that the system of military and church authority coincided territorially with each other to a high degree. In establishing authority in the Balkans, Byzantium largely relied on conditions linked with the epoch of Samuel and his successors. The aforesaid was reflected in the military system of power, although after 1018/1019, Byzantium adjusted it to its own needs, in particular the organisation of the Church. The Archbishopric of Ohrid preserved to a great extent the episcopal structure of the Bulgarian Church from the period of Samuel and his successors in the territorial sense, until some time around the middle of the 11th century. The insistence of Basil II on continuity with the previous, Bulgarian epoch (visible on the basis of the bishoprics that were assigned to it, its autocephalous position, the choice of a “domestic” archbishop) represents one of the consequences of the significance that the Bulgarian Church had, as an institution in the process of Byzantium's taking control of the region in the interior ofthe Balkans. Also the assumption is presented that the church organisation set upin 1018/1019, was a substitute for the poorly developed civil system of authority in certain Balkan regions. Although the Archbishopric of Ohrid represented the most enduring Byzantine achievement in the Balkans, the system that had been established under Basil II underwent many changes in the course of the second half of the 11th century. The most striking testimony of the advanced process of Rhomaization was visible in the creation of a tradition regarding the origin of the Ohrid Archbishopric, according to which it was connected with Justinian I. Importance was already attached to that theory in the time of the Ohrid Archbishop Leo (middle of the 11th century). Just before the mid–12th century, this theory led to overlooking the Bulgarian origin of the Ohrid Church, which was finally confirmed by the official acceptance of the title of the head of the Ohrid Church — the Archbishop “of the First Justinian and All Bulgaria” in the time after 1261.

More...

The fragments of three rulers’ images are preserved in the highest zone of the eastern wall of what is known as Gregory's Gallery in the exonarthex of the Ohrid cathedral. They are represented on each side of the images of the Deesis, with Christ on the throne, flanked by the images of two archangels, and two saints who mediate for the rulers. Based on the number of the ruler’s portraits, scholars assumed that these are the portaits of the Serbian emperor Dušan, his wife Jelena, and their son Uroš. Therefore, the mural paintings of the gallery are dated to the period between 1350 and 1355 because of the great stylistic similarity between the frescoes of the gallery and those on the first floor of the narthex which were painted by John Teoryanos and his assistants at the end of the fifth decade of the 14th century. One can reliably assume that the first ruler’s image from the left side of the north wall is, in fact, the portrait of the male member of the family. Such an assumption is based on the existence of the small fragment of an extremely long loros, a detail that was not observed by researchers. On the right side of the adjacent figure, a fragment of a semicircular decorative detail is preserved. This detail is reminiscent of the semicircular ornaments on the male sakkos. However, the possibility that the mentioned image is a portrait of the empress Jelena should not be excluded. Namely, one may think that the detail in question is, in fact, the fragment of a long, wide sleeve of a female ruler’s dress. Portraits of Jelena in Saint Nicholas Bolnički in Ohrid and in Lesnovo point to this conclusion. In addition, one should pay attention to the fact that the throne and the legs of Christ are intentionally directed to the south side. That is why we assume that the portait of Dušan was represented on that side, and the portraits of his son and wife who is nearer to Christ , were on the opposite, north side of the eastern wall of the gallery. Based on the existence of a supaedion, on which the figure nearest to Christ on the north side is standing, one can conclude that it is the image of the Virgin. The vertical decorative stripes on her dress are almost identical to those in the churches of Saint Demetrios in the Patriarchate of Pe}, Marko’s Monastery, Lesnovo and Konče. The assumption that the bishop represented on the opposite side of Christ should be identified as Saint Clement of Ohrid cannot be accepted without reserve. Namely, he was not represented with the long pointed beard that covers a part of his omophorion, as was the case on almost all of the images of Saint Clement. That is why the possibility that the image of some other holy bishop is in question seems more acceptable. One should especially examine the possibility that it was Saint Nicholas of Myra. Primarily, the only holy bishop that was represented in the Deesis in Eastern Christian iconography instead of Saint John the Forerunner was, as far as we know, just Saint Nicholas. As valid comparative examples, one can mention the images of the Deesis from the diakonikon of Sopo}ani, above the portal of the narthex of Saint Nicholas Domnesc in Kurtea de Arges, or the Deisis represented on the Russian icon from Tver, painted at the begining of the 16th century. It should be emphasized that Saint Nicholas was greatly respected during the reign of Dušan. This Serbian ruler had an almost personal attitude towards this saint and bishop. Evidence of this is Dušan’s gift to the basilica of Saint Nicholas in Bari, dedications of the smaller church of his mausoleum and the paraklession in Dečani, as well as from the texts of several of his charters. In some of the aforementioned documents, the mediating role of Saint Nicholas is especially stressed. Such a status was assigned to Saint Nicholas in the western part of the Dečani naos, as well. There is a “spatial Deesis” consisting of the figure of the Christ, the Virgin, Saint John the Baptist and Saint Nicholas. Finally, since Saint Nicholas was the namesake of the archbishop of Ohrid, there are grounds for assuming that it was the archbishop who wanted Saint Nicholas to be represented in the Deesis composition.

More...

Within the process of the reorganization of the Byzantine Empire, after the defeat of the Bulgarians in 1014, the Archbishopric of Ohrid, with 33 dioceses, was established in 1025. Christianizing missions on the Balkans, originating from Constantinople, which started in the second half of the 9th century, could be traced through the literary sources, changes in the funeral character and through the remains of church architecture. Also, after the archbishopric was founded, the massive use of items of personal religiosity began. Those items can be divided into encolpia, cross-pendants, small icons, medallions, ampoules and rings. So far, from the territory of the Archbishopric of Ohrid, more than 600 items of personal religiosity have been published. Since the original archbishopric covered the territories of several modern countries, these types of finds were not published. Although their number is not final, it can be said that this is a small amount of items of personal religiosity, used by the relatively numerous Christian population on the broad territory during the two centuries. The items of personal religiosity, which had an apothropaic use, represented also a sign of belonging to a new social group. According to the available data, the most numerous are finds of encolpia and cross-pendants, certain types of which are characteristic just for some parts of the Archbishopric of Ohrid, while the other groups of items of personal religiosity are much less represented. Most of the finds with a certain archaeological background were discovered in the rural cemeteries, where inhumation according to the Christian funeral ritual was practiced. In most of the cases those finds were sporadic, with the exclusion of the necropolis near the Church of St. Panteleimon in Niš, where a large amount of finds was found. The quantitative analysis of the items of personal religiosity indicates that, most probably, for the use of those finds, the level of the urbanization of a certain town and religious centre, such as Ohrid, Prilep, Niš, Braničevo and Durostorum, had great importance. The Archbishopric of Ohrid played a significant role in the process of the Christianization of the Balkans, since during the first two centuries of its existance the new religion was firmly established. The completely Christian funerary practice, the development of the church architecture and the use of the items of personal religiosity testify to this. However, relicts of pagan customs were also registered. Those were explained mainly as the consequence of the low level of the Christianization, although it could also be explained by the necessity of the people to reach out for all the available assistance of “higher forces” during hard times.

More...

Michael Psellos’ Chronographia is renowned as one of the masterpieces of Byzantine historiography and literature in general, but it is only in the last few decades that his subjectivity is not condemned by modern historians. Nowadays it is regarded as valuable for revealing the author’s attitudes and objectives in writing the history, especially if one considers that from the eleventh century onwards historians tend to figure in their works, starting with Psellos himself. He is, with Anna Comnene, the most prominent author in this regard, and his autobiographical “insertions” are so numerous and scattered through the text at many levels, that it can be said that he himself is the central character of his historical work. Psellos’ descriptions of characters are exceptional, and no other Byzantine historian can compare with him in this regard. Since he considered that emperors were key figures in creating history and major political changes, the Byzantine eleventh-century rulers were, at least on the surface, central figures in his historical work as well. Therefore, this paper deals specifically with their descriptions as presented by Psellos via their physical appearance and specifically one aspect of their illnesses. The descriptions of the emperors’ illnesses in the Chronographia are the means of characterizing them in a more candid and subtle manner, namely showing whether or not they were worthy of the imperial position they occupied. Therefore, we do not find any in the portraits of idealized emperors — Basil II, Constantine and Michael Doukas — nor in those of the emperors who were disqualified in other ways — Romanos Diogenes, Michael V, and Michael VI. In the strongly negative portraits of Constantine VIII, Romanos Argyros and Constantine Monomachos, the descriptions of illnesses are very detailed and brutal, and their physical appearance is otherwise disregarded (or, as in the case of Monomachos, his malady is placed in stark contrast to his beauty at the very beginning of his reign), thus showing their unworthiness of the throne. Not even the emperors whom Psellos observed as mainly positive — Michael Paphlagon and Isaac Komnenos — are spared these descriptions, which are carefully and intentionally placed so that they are connected with their misdeeds and thus indicate the punishment for their behavior. The true meaning of the emperors’ illnesses in the Chronographia is further revealed with the metaphor of the illness of the Empire, which is placed near the end of the first part of the history. Psellos here presents the decline of Byzantium in the period he deals with in the Chronographia by using medical terminology and indicating that the emperors after the death of Basil II led “the body of the state” (to swma thj politeiaj) into a state of utter decline and sickness, although Isaac Comnenus tried to cure it, but he used the wrong measures that were too abrupt. In this way, Psellos gives us guidance on how to read his long passages on the maladies of the emperors.

More...

In 1149, the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos had left Pelagonia, heading the campaign against the Grand Prince Uroš II, who had been attacking the Byzantine territories. The aim of the campaign was the town of Ras, soon conquered by the Emperor; afterwards, he devastated the region of Nikava, from where he headed to the Ibar valley; there he besieged and captured the town of Galič. The region of Nikava was encompassing the territory between the today’s region of Rožaje and Štavice. That is the territory through which led the roads between Ras and the region of Polimlje, between Shkoder and Ras, between Ras and Metohia, as well as the road to Pešter and the Ibar valley. Since the antique times, this region was well guarded; the remnants of more than 25 fortresses dated 4th to 6th century had been preserved. The region of Rožaje and Štavice is identical to Kinnamos`s description, and its position is in concordance with the military logic of the campaign. Also, the name of the river Makva, situated near the source of the Ibar River, indicates etymologically to Nikava.

More...

Keywords: North Macedonia; Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC); Security Forum; NATO; fighting corruption;

More...

Keywords: glass beads; Meroitic and late Antique Nubia; trade in antiquity; glass manufacturing; chemical composition; provenance study

Strings of colorful glass beads were a popular commodity traded throughout ancient Nubia in the earlier half of the first millennium AD. Combining macroscopic examination with laboratory analyses, the author breaks new ground in Nubian studies, establishing diagnostic markers for a study of trading markets and broader economic trends in Meroitic and post-Meroitic Nubia.Archaeometric results, lucidly presented and discussed, identify the origins of the glass from which the beads under investigation were made. The demonstrated South Indian/Sri Lankan provenance of some of the ready-made beads from Nubian burial contexts and a reconstruction of their distribution patterns in Northeast Africa is the first undisputed proof of contacts between Nubia and the Red Sea coast. Reaching beyond that, it shows Nubia’s involvement in the Asian maritime trade, whether directly or indirectly, during a period of intensive interchanges between the 4th and 6th centuries AD.

More...

Keywords: Balkans; Ottoman Period; pottery; standardisation; pottery production; social identity

Glazed pottery from the Belgrade Fortress, already evaluated contextually and typologically, allow us to address some important issues of pottery production and craft specialisation in the Ottoman period (16th—17th centuries). In order to determine the degree of pottery standardisation, this article will analyse the main production parameters, such as shape, size/volume and production technology. The production organisation and craft skills in all aspects of pottery making are examined as well.

More...

Keywords: Lebanon; Beirut; Post-medieval period; Ottoman period; pottery; ceramic; grafitta tarda; majolica; Didymoteicho; Çanakkale

Whereas historical, political and cultural studies reach the postmedieval period in Lebanon, interests for archaeological artifacts remains neglected.The archaeological excavations undertaken in 1996 and 1997 in Beirut, sites Bey 070, Bey 071 and Bey 111, led to the discovery of tableware ceramics (in the surface layers) dated to the 16th —19th centuries.In this paper, we examine tableware ceramics of various origins: Didymoteicho and Çanakkale (Thrace), Kütahya and Iznik (Analolia), Pisa and Montelupo (Tuscany), Albisola in Liguria, Varages in Provence, European porcelain, as well as local and/or regional ceramics.

More...

Keywords: Byzantine White Ware; 10th century; dishes with hollow stem; lid; inscribed and impressed sub-glazing decoration; old-Bulgarian monastery; import

In the article we publish the collection of 11 complete and two partially restored dishes and one lid, found during the excavations in the old Bulgarian monastery at the village of Ravna, Provadia region. They were found in fragments in the yard and in a room near the representative building, which could be considered as the residence of the abbot and of the visitors of the monastery. All of dishes are import from Byzantium, dating around the middle of the 10th c. The stratigraphic data allow us to determine the upper limit of their use to be before the burning of the monastery, which most probably happened during the events in Bulgaria during 969—971. Judging by the technique of manufacturing and the decorations, the dishes belong to the so-called Glazed White Ware. They are covered with dark-green or grass-green and light-yellow or yellow-brownish glazing. There is also inscribed or impressed decoration under the glazing.The goal of this publication is to focus the attention of the specialist on Byzantine pottery in the collection, to determine more precisely its dating and a possible place of manufacturing.

More...

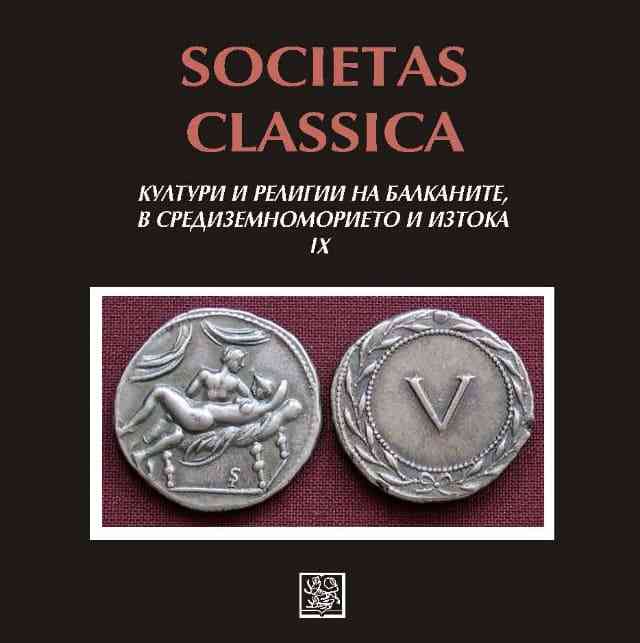

Keywords: Crimea; Byzantium; Balkan region; Middle Byzantine period; funerary sites; pentagram / pentalpha rings

A finger ring with a pentagram was found in tomb 7 of the Gorzuvity necropolis, which served as the basis for this research in order to study the origin and the distribution of such jewelry, to identify analogies and to clarify their dating. Parallels from the South-Western Crimea and from other territories of the Byzantine world are given. A study of sample of such rings allowed us to identify several features that are most characteristic of the 10th—12th centuries. On this basis, the ring with pentalpha from Gorzuvity necropolis was previously dated to the 9th—11th centuries, not excluding the 12th century. Perhaps, with the help of the natural science methods implemented at present time, we will be able to clarify this date. The pentagram rings are of Byzantine origin, since they were distributed both in Byzantium itself and in its adjacent territories. Considering the finds from closed complexes, the rings appear in the 6th—7th centuries, the most widespread being from the 9th to the 11th centuries, their number dropping in the 12th century. Apparently, it was not an expensive mass production, these products being worn by citizens and residents of settlements. Such rings had an apotropaic character, because the image of the pentagram was supposed to ward off misfortune and evil from a person, whereas the signs of wear indicate that these jewelries were worn daily. Pentagram rings certainly reflect Byzantine fashion, they demonstrate the aesthetic and religious preferences of the peripheral population and testify to a uniform culture in the Byzantine world in the Middle Ages.

More...

THE ESSAY READS KRISTEVA’S INTERDISCIPLINARY WORK ALONG THE TRAJECTORY OF A SECRET NARRATIVE: THE NARRATIVE OF EXILE AND DISCONSOLATE WANDERING. THE CLAIM IS THAT KRISTEVA’S THEORETICAL MOVEMENT TOWARDS A FOREVER LOST OBJECT RETURNS AS THE PARABLE OF A FLIGHT AWAY FROM THAT OBJECT. THIS READING OF THE THEORETICAL VIA THE FICTIONAL UNCOVERS, HENCE, A HIDDEN MAP OF THE “LOST TERRITORY” (BULGARIA) AND ITS FORGOTTEN LANGUAGE. THE DARKENING OF THIS MAP WHICH BURSTS “ON THE FAR SIDE OF LANGUAGE” INTO SERENE IRIDESCENT SPACES PROVIDES A MODEL ABOUT THE WAYS IN WHICH KRISTEVA SPEAKS OF DARKNESS THROUGH LUMINOSITY, OF SILENCE THROUGH POLYGLOTTISM, OF THE NATIVE THROUGH THE FOREIGN, OF THE MARGINAL THROUGH THE CENTRAL, AND OF WOMEN THROUGH MALE MASQUERADE.

More...

Keywords: Putna Monastery; Byzantine Music; Protopsalter Eustatie; Stephen the Great; Musical Manuscripts;

The Voivodal Monasteries were spiritual centres, and also centres of Romanian culture and life. Within all these bastions of faith, there functioned actual schools and workshops of painting, sculpture, embroidery, precious metal crafting and schools of copyist and calligraphers.The Putna Monastery, the “Romanian Jerusalem”, as M. Eminescu called it, had such workshops and schools from its beginnings. First, we must mention the Musical School founded by Eustatie, the protopsalter who left a few manuscripts to us, which generated some disputes over their originality. Specialists in Byzantine musicology proved that the Musical School in Putna has its own originality, even if it appears within the context of certain Slavic- Byzantine influences.

More...

Keywords: Polish Philhellenism; Polish diaspora in Greece; Polish-Greek relations

The article points to the history of Europe in the nineteenth century. The dominant role on the continent at that time was played by the powers that led to the annexation of both Polish and Greek lands. The Polish lands came under the rule of Austria, Prussia and Russia, while the Greek ones came under the rule of Turkey. In 1830, however, a Greek state was established. Gradually during this time, relations between the Poles and the Greeks began to be established, which resulted in the appearance of a small Polish diaspora in Athens and other Greek cities.

More...

Keywords: Albanian Diaspora; Arbëresh; Arbëresh Traditions; Siege of Coron; Migration; Music and Migration;

This is one of the best-known songs of the Albanian diaspora (the Arbëresh) in Italy. The song lyrics are replete with homesickness for a land which was left and is never to be seen again. Curiously enough, this land is Morea, in the south-west of the Peloponnese in Greece. The name Morea is connected with the exodus of the Arbëresh to southern Italy and Sicily after the fall of Koroni to the Ottomans during the Siege of Coron, 1532–34. The question is, why has this particular song become a symbol of the exodus for this diaspora? The answer lies in the visible and non-visible parallel worlds of the song as well as those projected into it. These will be the main focus of this article. The first mention of the song is in 1775, though the metric structure indicates an older origin. Arbëresh intellectuals and priests have provided important information about the customs and rites of which the song has been part and, despite their romantic view, they have helped scholars to recognize the magical-religious context from which the song originated and how it has been transformed to the “nostalgic hymn” known and performed today also among Albanians in the Balkans.

More...

Keywords: Byzantine Liturgy; Eucharistic Anaphora; Sacrifices; Textual Criticism; Old Testament Theology; Liturgy and Bible;

This paper explores the hermeneutical background of the response to the final diaconal acclamation prior to the initiatory dialogue of the Eucharistic anaphora currently used in both Eucharistic formularies of the Orthodox Church, those of St Basil and St John Chrysostom. Specifically, this study examines the response, «Ἔλεον εἰρήνης, θυσίαναἰνέσεως», to diaconal command, «Στῶμεν καλῶς· στῶμεν μετὰ φόβου· πρόσχωμεν τὴν ἁγίανἀναφορὰν ἐν εἰρήνῃ προσφέρειν». After presenting the historical data and variants of the above response (as found in patristic quotes, liturgical commentaries, manuscript variants, ancient Latin translations and other Eucharistic formularies such as the Hagiopolite Liturgy of St James), this study provides an outline of the way in which contemporary experts in the field of liturgiology have understood this phrase. To follow, this paper explores the syntactical structure of the response in relation to the preceding acclamation. Particular analysis will be made of the grammatical and syntactical use of the present, active, infinitive«προσφέρειν». Finally, this paper demonstrates that the response in its current form offers a specific biblical hermeneutical understanding of the Eucharistic oblation (anaphora) in relation to the Old Testament sacrificial offerings.

More...

Keywords: Byzance; art; theology; icon; canon; tradition

Considering the category of the Byzantine canon Yuri Lotman remarks that, looking from the historic point of view, it is not the transition from one sign to another, but going deeply into the sign. The new text remains always the new-discovered old text. Byzantine art is generally sacral art, and it’s strictly connected with the experience of orthodox faith. The art finds its expression in the canon. The faith finds its expression in the dogma. Therefore the histories of Byzantine art and of Byzantine theology are related. Their turning-point is Iconoclasm, that concludes the period of formation of Christian dogma and of iconographic canon. After the last Council (787) and the Triumph of Orthodoxy (843) the dogma of faith and the dogma of art is generally configurated. It is the period of consolidation and contemplation the dogma and the canon, the period of “going deeply into the sign”.

More...

The paper presents some aspects of the Byzantine policy in the Mediterranean during the second half of the 13th Century. Emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus (1259–1282) wants to restore the Byzantine fleet and for this purpose invested a lot of money. This fleet should become a rival of Venice and Genoa. The efforts of the emperor realized partially. Оnly part of the Greek Islands are exempt from Latin rule. But Byzantine diplomacy managed to restore its influence in Western Mediterranean. The Reign of Michael VIII was the last period when Byzantium again rise as a Mediterranean power.The paper presents some aspects of the Byzantine policy in the Mediterranean during the second half of the 13th Century. Emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus (1259–1282) wants to restore the Byzantine fleet and for this purpose invested a lot of money. This fleet should become a rival of Venice and Genoa. The efforts of the emperor realized partially. Оnly part of the Greek Islands are exempt from Latin rule. But Byzantine diplomacy managed to restore its influence in Western Mediterranean. The Reign of Michael VIII was the last period when Byzantium again rose as a Mediterranean power.

More...