We kindly inform you that, as long as the subject affiliation of our 300.000+ articles is in progress, you might get unsufficient or no results on your third level or second level search. In this case, please broaden your search criteria.

Describing the Jewish communities in the multi-religious history of Iraq can only take place from a historical perspective, simply because they no longer exist. Apart from a few individuals, there is no future perspective at this point in time.

More...

The study uses methodology “cultural memory studies” to feature the National Theater as a place of memory. It focuses on the building as a symbol and attempts to describe the way, in which the symbolic architecture represents the past and enters the memory praxis of the nation (decoration of the theater, canonical repertoire, festivities, collections and so-called theater trains as actions of national participation). The author adds a dynamic extent of remembrance to a traditional approach – place of memory as a depository of representations of history. He contemplates the National Theater as an “empty place” – a framework of a specific social and cultural context to deliver substance of the past. The study analyses the process of the National Theater constitution as a place of memory – especially in the connection with the 1881 fire. This “national tragedy” symbolized one of the most powerful experiences of the modern Czech nation, that as a strong shared affection reflected itself in the process of constitution of the national identity. In this instance the study utilizes theme of trauma used by Aleida Assmann in the frame of the memory studies. The study uses a few cases to demonstrate memory praxis closely linked to a symbolic space of the National Theater (production of the Čapek’s theater play the White Disease (Bílá nemoc) in 1937, role of the theater during political changes in 1989).

More...

In the article I discuss the process of Engels’ search for a social alternative in the conditions of the pre-revolutionary crisis that struck Europe in the early 1940s. Twenty-two-year-old Engels became enthralled with it when he arrived in London in November, 1842. He was young, rebellious, of a brilliant mind and exploratory spirit. He belonged to a generation whose youth coincided with the culmination of the crisis of the Restoration period. Against this background, I want to look at the period that Engels spent between November 1842 and April 1845 in Manchester, where he arrived from his parents’ home in Barmen.

More...

The article starts from the thesis that one of the main causes of the problems of building socialism in the 20th century is the neglect of morality in classical Marxism, analyses this neglect through a comparison of utopian and scientific socialism, and briefly follows Engels’ development from utopian socialism to scientific socialism and back. The conclusion is that the lack of morality in classical Marxism is not accidental, but that it is precisely this property that makes it untrue, but also an extremely effective socialist ideology at a time of the great crisis of capitalism. Such an understanding of Marxism is consistent with the important Marxist idea that the purpose of ideologies is not to be true, but to strengthen the economic system. In this sense, Marxism is an ideology of the collapse of capitalism.

More...

The paper deals with a relation between historical materialism and idealism – while proving idealism to be a profoundly conservative point of view – proving the thesis through an example of the contemporary political discourse of Zoran Milanović, and his so-called “liberal progressiveness”. Holy Family – Critique of Critical Critique can be read via contemporary examples that supplement materialistic interpretation of liberalism/idealism with the psychoanalytical interpretation of suppression of class conflict. A nature of liberal interpretation of the world vis-à-vis materialistic insights (undoubtedly and with clearness) epistemological and not only by facts – can be seen from The Condition of the Working Class in England, a study of young Engels that will be taken as a foundation of the materialistic understanding of the modernity and related figure of an unaccommodated man. A fundamental possibility of an overcoming of dialectical paradox in the figure of a proletarian as an unaccommodated man (while avoiding idealistic “displacements”), can be found in the development of technology as a possibility of overcoming of the capitalistic mode of production, as a foundation of development and personal freedom that can be achieved only in the community.

More...

Pactul dintre Hitler şi Stalin, semnat la 23 august 1939, stipula într-un protocol secret interesele sovietice de a anexa Țările Baltice, estul Poloniei şi estul României – teritorii care niciodată nu i-au aparţinut. La 28 iunie 1940, Armata Roşie a trecut Nistrul ocupând Basarabia, nordul Bucovinei şi ţinutul Herţa. Ceva mai târziu, la 2 august, ignorând interesele populaţiei băştinaşe şi încălcând legislaţia internaţională, chiar şi pe cea sovietică, o parte din teritoriul Basarabiei – şase judeţe: Bălţi, Tighina, Chişinău, Cahul, Orhei şi Soroca – şi şase din cele 13 raioane ale R.A.S.S.M. – Tiraspol, Grigoriopol, Dubăsari, Camenca, Râbniţa şi Slobozia – sunt incluse forţat în componenţa Republicii Sovietice Socialiste Moldoveneşti. În acelaşi timp, teritoriile româneşti din nordul Bucovinei, ţinutului Herţa, nordului şi sudului Basarabiei, pe baza aceluiaşi scenariu, sunt incluse în componenţa Republicii Sovietice Socialiste Ucrainene.

More...

The periods of deep political and social quakes always bring reconsideration and rearrangement of the events that happened in the past. Disappearance of ideological paradigm, changes in global politics and epochal consciousness affected the return of the pre-socialist past, its romantization and idealization, as well as revisionist change of social determinants that were used for historical interpretations in post-socialist countries with the intense action of politics, nationalism and history in their historiographies. Even the bigger historiographies like Russian, are not immune from political pressure in relation to its own history, and histories of other countries and nations. There are many differences between the Soviet and the modern Russian historiography, as well as their forms. Due to the wish to control history, the international and class principle gave its place to the more active, national one, with the renewal of its identity that is clean from communist influence. Interests and politics of superpowers leave a huge mark in the history of the Balkan nations. Political disputes and positioning affect the historiographies and they play a big role in determining the topics that need to be researched. Dissolution of Yugoslavia and the emergence of new post-Yugoslav states on the European political map worsened the efforts of Russian historians in analyzing and researching their past and modernity. The increase of Russian interest in researching the history of Bosnia and Herzegovina is related to the political crises and conflicts in that area and wider Balkan context. Their attention is mostly focused on the Eastern Crisis (1875–1878.) and the Bosnian / Annexation crisis (1908–1909), dissolution of the SFRY and the “post-Yugoslav” wars. They also do research about the events that occured in this area in the last decade of the 20th century and at the beginning of the 21st century.

More...

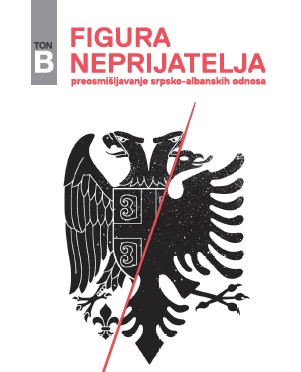

In this paper we examine to which extent was egalitarian vocabulary of Yugoslav socialism able to provide an alternative framework for interpretation of Serbian-Albanian relations. Our initial hypothesis is that – due to the experimental nature of Yugoslav self-management socialism, which implied certain compromises with liberal capitalism – the Yugoslav elite was structurally bound to systematically negate the social aspect of protests that took place in Kosovo in 1968, 1981 and 1988. Using critical discourse analysis on daily newspapers (Politika, Večernje novosti and Borba), we show how the nomenclature treated the complex social-political aspects of the social uprisings exclusively as a manifestation of nationalism. To the actors involved, this discursive strategy suggested that nationalism is a common denominator for economic, political and ethnic equality. Final consequences of these discursive strategies will be shown through analysis of media coverage of protests in Kosovo and the “Brotherhood and Unity” meeting that took place Belgrade in 1988, wherein we can see that there is little space left for non-nationalistic interpretation of any kind of social uprising, both in media and actors’ perspective.

More...

Almost in parallel with the withdrawal of the Axis troops from the Taman area in the Caucasus, the Soviets prepared a bold landing action on the Kerch peninsula in Crimea. The landings, carried out in two areas, south and north of the city of Kerch, were aimed at supporting the offensive from the north of the Sea of Azov and capturing Crimea. The present study focuses on the naval actions that took place predominantly in the area of the southern bridgehead, where the Axis naval forces were able to block the supply of enemy troops.

More...

The Soviet Union is one of the old political forces that coerced or voluntarily held together ethnic or religious origins. It is a power that has left a very deep history in its past. The bipolar system in the world came to an end after the Cold War. After this situation, ethnic conflicts increased and spread to the Soviet Union in the 1980s and caused great repercussions in the world (Aslanlı, 2013). Conflicts occurring in the world have been a threat to security. These conflicts resulted in disintegration and in the early 1990s, the USSR was replaced by 15 new independent republics at the end of 1991 (İbadov, 2007).

More...

Ever since Tito’s death in 1980, the socialist Yugoslavia was going through difficult political, economic, and social temptations, involving ample domestic and international actors, along with the accompanying consequences of the era change of on a global level. The Yugoslav state crisis should be observed in a broader context which will provide a more complete answer. The remaining two fundamental pillars of the Yugoslav federation – Yugoslav Communist Party (SKJ) and Yugoslav National Army (JNA) ‒ were undermined in early 90’. The then republics’ elites, guided by partial interests, mutually confronted to one another, were not ready to adequately face the challenges of democratization that captured the Eastern euripi following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. The Yugoslav republics took numerous legal steps towards strengthening their own sovereignty. The crisis culminated in 1991 with the separation of Slovenia and Croatia from Yugoslavia, and the armed conflicts that followed. Confronted with the new legal and political surrounding, Bosnia and Herzegovina also began with the revival of its independence. This path proved to be extremely difficult and challenging, mainly due to the revived great-Serbian and great-Croatian attempts to divide Bosnia and Herzegovina, particularly expressed in 1991 during the negotiations between Slobodan Milošević, president of Serbia, and Franjo Tuđman, president of Croatia. In early days, these plans, with a strong support of regime affiliated media from Belgrade and Zagreb, manifested in form of numerous obstructions in the operation of the highest authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, promotion of a thesis that Bosnia and Herzegovina cannot survive as an independent political entity, establishment of illegal Serb communities of municipalities and regions, and then Serb Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croat ones in form of regional communities, whereby the most significant one was Herzeg Bosnia. In such complex circumstances, and in line with the recommendations of the Badinter’s Commission, referendum on independence was organized in 1992, when the citizens firmly voted in favor of independent Bosnia and Herzegovina. European Community recognized Bosnia and Herzegovina on 6th of April, while the USA did it on the following day. In conditions of aggression and four year long war destruction, a new chapter in legal and state development of Bosnia and Herzegovina began.

More...

Au cours des dernières semaines, de nombreuses voix se sont élevées pour signaler la crise du mouvement étudiant en Tchécoslovaquie. Pour que nous puissions serrer de plus près la situation créée, en chercher les sources et les solutions qui apparaissent, je propose une excursion historique dans laquelle j ’aimerais dessiner l’évolution du mouvement étudiant à Prague au cours des cinq, six dernières années, c’est-à-dire durant la période où ce mouvement n’a pas perdu sa continuité. Je ne parlerai qu'occasionnellement de la vie estudiantine dans les autres villes de Tchécoslovaquie, surtout parce que l’importance des événements estudiantins dans ces secteurs est proprement provinciale, et presque toujours une conséquence des événements praguois.

More...

Restrictions to freedom and forced labour in the Croatian, that is Yugoslavian, legal system following the Second World War, during the period of “National Democracy,” was determined by a series of decrees, resolutions, and laws. From 1945 to 1951, the Yugoslavian penal code recognized four types of non-free labour: forced labour without the removal of personal freedom, forced labour with restrictions to personal freedom, corrective work and socially useful work. This article, on the basis of sources, literature, and above all the most important decrees, resolutions, and laws applied in Croatia, and elsewhere in Yugoslavia, during the period of “National Democracy”, from 1945-1951, reviews the matter of state repression and the question of the restrictions to freedoms and forced labour in the penal code.

More...

Forced labour for the Germans of Vojvodina was introduced in the first days after the new government was established. It was an expression of the necessity of making up shortages in the supply of labour as it was also seen as a punishment for the German minority’s support for the Axis powers during the Second World War and the participation of some of its members in war crimes. Some people were marched under armed guard to work in forests, fields, vineyards, the clearing of rubble, the construction or repair of buildings, roads, railways, and bridges, while some people were concentrated in special camps from which they were taken to work every day. The organization of work camps overlaps with the period of martial law, while the whole process took shape in stages, in an attempt to concentrate labour supply, preserve Ger-man property, open areas for the settlement of colonists and others. Conditions in the camps were inadequate in terms of supporting and maintaining the ability of inmates to perform work, and there was a lack of any motivation to improve them. In the autumn of 1947 it became clear that the policy toward the German minority was changing, and in the spring of 1948 the Communist authorities began to dismantle the camps. Because of these types of conditions and the fact that in the first years following the dismantling of the camps their work in large measure retained the qualities of forced labour, a large majority of Volksdeutsche decided to emigrate from Yugoslavia when this became a legal possibility. Their work, instead of contributing to the development of their homeland, contributed to the West German “economic miracle.”

More...

The work follows the evolution of the position of political convicts in Serbia in post-war period. Shortly after the end of the war, the position of political convicts was extremely bad and the prisoners were often subject to brutal torture. Prison conditions underwent gradual evolution in the period between 1953 and 1985, so that since the beginning of 50s, and especially during 60s and 70s, they grew better and better. Still, their improvement was limited by material as well as political and ideological factors and remained behind the standards of the west democracies.

More...

After the collapse of the second Yugoslavia all the official bonds that Croatian historiography had with other former Yugoslav historiographies were broken. Still, the cooperation among historians was soon renewed, especially between Croatian and Serbian historians through participation on the international scholarly conferences called Dijalog povjesničara / istoričara (Dialogue among historians) organized by Foundation Friedrich Naumann. During eight years (1998-2005) the foundation organized 10 conferences, and published the conference proceedings. These conferences managed to gather 165 participants (from twelve different countries), who delivered their papers and worked in the form of workgroups. The most important part of these conferences is the fact that they were organized without any political influence, though many participants emphasized idea of international and internal reconciliation project. However, this reconciliation does not include political reconciliation but only reconciliation with the past. Throughout the years, these conferences showed that historians from both countries can cooperate and exchange ideas without any significant problem but only in the framework of a scholarly dialogue.

More...

Franjo Tuđman, an academician, Ph. D., and the first president of the Republic of Croatia, published his first text in Belgrade in 1952, a publicist article about a current military topic that he published as an officer of the Yugoslav National Army (JNA). He published his first article about the subject matter of this paper, history, in 1954 in Krapina. It was another publicist article about his home region of Hrvatsko zagorje in the People’s Liberation Struggle, in which he had been an active participant as a member of the Communist Party of Croatia and the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. His writing was politically intoned in the customary post-Stalinist register. He wrote his first works of historiographical value after he was moved to the study department of the Supreme Command in Belgrade in 1957, and his works after 1961 were written outside of the confines of the Army at the Institute for the History of the Workers’ Movement in Croatia, whose co-founder and first director Tuđman had been. Addressing the topics that are the subject matter of this paper, he developed into a distinguished scientist (Europe), holder of a Ph. D. (Zadar), and an associate university professor (Zagreb). In addition, at the Institute he influenced the professional development of a number of other distinguished Croatian historiographers who researched this and other subjects. He strove to adhere to the globally recognized scientific and professional standards of the time, set forth in Croatia by Jaroslav Šidak: he based his writings on sources and on critical contemplation of literature (both Yugoslav and foreign), and he made his own historiographically useful scientific and professional judgments and assessments. The antifascist and supernational ideas are prevalent in his work, but the Croatian national idea also gains importance as time passes by. His writings have held their value, but have for the most part been (unjustly) neglected in comparison with other writings he produced after the 1970s, when he, expelled from the League of Communists of Croatia and the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, removed from the position of the director of the Institute, and no longer allowed to teach, functioning as a prisoner and active politician, supplemented his old writings about this subject with new, mostly publicist values characterized by prominent Croatian national spirit in the contemporary anti-communist and anti-Yugoslav political standing. Still, his overall contribution to this subject is positive, and he also provided very vigorous impetus to his critics and followers, including scientists and experts, regardless whether their views about his work were positive or negative. Some of them made their own new contributions to historiography and publicist writing by defending or rejecting his theses and results, sometimes even unwittingly. These solid results about this subject would be nonexistent without Franjo Tuđman.

More...

The duration and intensity of warfare in Yugoslavia and the Independent State of Croatia, the presence of significant occupation forces of the German Reich, Italy, and Hungary, and the activities of NDH Army, the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland (the Chetniks), and the People’s Liberation Army and the Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia / Yugoslav Army resulted in direct conflicts between the warring parties, which led to severe human losses among the soldiers and civilians alike. The irreconcilable ideologies and political and military interests in the armed conflict and the civil war multiplied the casulaties.

More...

The Albanians in the inter-war Yugoslavia were an unwanted and unwilling national minority. They became subjects of the Kingdom of Serbia in 1912 and then of Yugoslavia in 1918. They were unhappy to be Yugoslavia’s citizens and the Yugoslav authorities weren’t happy to have such citizens. It is not true that they weren’t recognized as a national minority (as it is often claimed), but it is true that they were denied most of the rights other national minorities were accorded. In other words, the Yugoslav powers-that-be never made an attempt to win the Albanians over for the new state. The most they did was to make deals with part of the Albanian élite.

More...