We kindly inform you that, as long as the subject affiliation of our 300.000+ articles is in progress, you might get unsufficient or no results on your third level or second level search. In this case, please broaden your search criteria.

The Romanies in Kragujevac have a destiny similar to those in other cities of Serbia: as a group, they are at the most extreme margin. Living isolated from the social trends, in an almost parallel world, they do not have any social power. The society doesn’t show interest in them and their problems, while only some individuals have an understanding of civil and collective rights. Many Romanies are not able to realize the basic civil and collective rights because they are not aware of them. More often than not, the institutions in charge, which should protect their rights, tend to reject them, rather than provide them with necessary help. The position of Romanies has got additionally worse with the wide-spread pauperization of society. A substantial number of Romanies who had been working in “Zastava” were fired. They are now either registered with the Bureau of Employment, or selling goods at the flea market. Some categories of the Romany population are in an extremely difficult position: refugees from Kosovo, deportees from the Western countries, and child beggars without parental guidance or care.

More...

Evropska unija funkcioniše na principu vladavine prava tako da su sve njene radnje utemeljene na ugovorima na čiji sadržaj su dobrovoljno i demokratskim putem pristale sve države članice EU. Pravni instrumenti Evropske unije (EU) su podijeljeni u dvije grupe. Prvu grupu čini takozvano primarno zakonodavstvo EU – osnivački ugovori; Ugovor o Evropskoj uniji (UEU), poznat i kao Ugovor iz Mastrihta iz 1992. godine, Ugovor o funkcioniranju Evropske unije (UFEU) te Povelja EU o temeljnim pravima. Obaveze iz ugovora jesu postavile temelje za EU politike rodne ravnopravnosti i imaju posebnu težinu. One su provodive od strane država članica, EU institucija, kao i – zahvaljujući doktrini o njihovom direktnom efektu – od samih građana EU pred domaćim sudovima. Sekundarne izvore prava čine pravilnici/uredbe, odluke, preporuke, mišljenja te uputstva/direktive, koje su obavezujuće u smislu rezultata. To znači da su države u postizanju definisanih ciljeva slobodne da odluče o najboljem načinu njihove implementacije (čl. 288 UFEU).

More...

Postojanje institucionalnih mehanizama za ravnopravnost spolova se smatra bitnom pretpostavkom za ukidanje diskriminacije na osnovu spola/roda i ostvarivanje ciljeva rodne ravnopravnosti. Potreba za uspostavljanjem institucija koje će se specifično baviti ovim pitanjima je prepoznata i istaknuta tokom Četvrte svjetske konferencije o ženama 1995. godine u Pekingu (vidi rad II.1 Ujedinjene nacije autora Damira Banovića). Zaključci ove konferencije su sadržani u Pekinškoj deklaraciji i Platformi za akciju kada je zaključeno da vlade imaju primarnu odgovornost za sprovedbu Platforme za akciju te da bi mehanizmi i institucije za unapređenje položaja žena trebali sudjelovati u formuliranju javne politike i poticati sprovedbu Platforme ali i djelovati kao katalizator u razvoju novih programa (Platforma za akciju, 1995, Glava V-A). Komitet za eliminaciju diskriminacije žena Ujedinjenih naroda (Opća preporuka br. 28, 2010) preporučuje postojanje ovih institucija kao jednu od osnovnih pretpostavki za sprovođenje člana 2. CEDAW konvencije.

More...

Postizanje rodne ravnopravnosti kao ljudskog prava propisano je ustavima i zakonima o ravnopravnosti polova/rodnoj ravnopravnosti, antidiskriminacionim zakonodavstvom i cijelim nizom međunarodnih instrumenata ljudskih prava koje smo obavezni poštovati i primjenjivati. Odredbe kojima se štiti ravnopravnost i zabranjuje diskriminacija po osnovu pola/roda dio su i sistemskih i drugih propisa u različitim oblastima, od zakona, podzakonskih i drugih akata, pa sve do strateških i planskih dokumenata, odnosno javnih politika. U čemu je onda problem, pitamo se. Zašto ove deklarativne odredbe u zakonima ne znače odmah i njihovu primjenu u stvarnosti? Zbog čega i dalje postoje izražene rodne neravnopravnosti, pa čak i diskriminacija i nasilje kao ekstremni oblik diskriminacije? Zašto određene mjere vlasti imaju različite učinke na različite društvene grupe muškaraca i žena? Zašto naoko neutralne norme imaju nejednake efekte, iako nejednakost ili čak diskriminacija nisu uopšte bili namjera zakonodavca ili donosioca neke mjere? Zbog čega „ne vidimo“, odnosno odbijamo da vidimo da rodne nejednakosti postoje i da je njihovo uporno opstajanje zapravo legitimisana nejednakost u moći, podjeli rada i pristupu resursima?

More...

ljudska prava se temelje na pojmu urođenog dostojanstva svih ljudskih bića. Univerzalna su, neotuđiva, nedjeljiva i međuovisna. U Bosni i Hercegovini ljudska prava se štite na nivou države, kao i na nivou entiteta. Ustav Bosne i Hercegovine, te ustavi entiteta, na specifičan način štite ljudska prava, kroz direktnu primjenu Evropske konvencije o zaštiti ljudskih prava i osnovnih sloboda.

More...

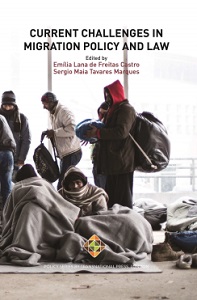

The objective of this research paper is to examine the valorization of procedural rationality in the field of fundamental rights related to migration from non-EU countries. This is in the context of an EU which is strengthening its constitutional nature, which sees a transition from the concept of government to the concept of governance. In this legal environment it is crucial to guarantee the effectiveness of fundamental rights, thus increasing their normative scope with regard to migration. The challenge to European governance practices and structures is how to transform the valorization of procedural rationality to essential rationality. This leads the democratic praxis to re-appropriate its origin. Nevertheless, this concept of procedural rationality establishes soft law as the fastest and most flexible solution to the migration challenge.

More...

This chapter assesses whether national law, policies and practice in the field of unaccompanied asylum seekers are in compliance with international conventions including the UNHCR guidelines and UN convention of the rights of the child (CRC). We will discuss policy and practices on minors exposed to human trafficking, taking Norway as a case. The Norwegian Immigration Act of 2008 includes provisions and formulations intended to strengthen the legal position and rights of asylum-seeking children as children. The intention was to ensure that national regulations on immigration were in accordance with the CRC and in line with the Norwegian Human Rights Act 1999. The CRC as well as UNHCR guidelines mention human trafficking, including forced labour and sexual exploitation as one main threat to which children may be exposed. The chapter discusses three scenarios which represent distinct forms of how unaccompanied minors are recruited into exploitative relations on their way to or in Europe and how their cases are assessed when applying for asylum in Norway as unaccompanied minors. Ways into and out of exploitation may have decisive implication for how their asylum applications are assessed and for further access to rehabilitation measures.

More...

This chapter describes and proposes a new social inclusion model for supporting unaccompanied minors in becoming autonomous, as they are one of the most vulnerable groups of contemporary migration flows. According to the Committee on the Rights of Children “unaccompanied children (also called unaccompanied minors) are children, […] who have been separated from both parents and other relatives and are not being cared for by an adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing so” (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2005).

More...

People who fled their countries of home voluntarily or forced have been described as refugee, migrant, and person with temporary protection in the countries hosting them. The challenges faced by these uprooted people seeking security have forced many countries to develop and formulate new migration, asylum, and refugee policies.

More...

Populist radical right oppositions to international migration from Islamic countries are argued to undergo a discursive change from ultranationalist and religious constructs to –misleadingly– liberal argumentations, claiming that European liberal democracy is under threat of migration (Brubaker, 2017, pp.1191-1226; Hafez, 2014, pp.479-499; Börzel & Risse, 2018, pp.83-108; Börzel, 2016, pp.8-31). The present study aims to demonstrate how these ‘liberal’ grounds for objecting migrations exist at European (supranational) level, and explores the conceptions of liberal democracy used by pan-European radical right in opposition to migrant and minority rights. Therefore it asks how mainstream populist radical right factions represented in the European Parliament debate migrant and minority rights and what conceptions of liberal democracy emerge within their debates. It orients this question to two plenary sessions held in the European Parliament, in the shadow of the EU’s refugee crisis, to discuss the situation of fundamental rights and terrorism in Europe. Recent refugee debates in the EP have the potential to shed light on this issue, as the way populist radical right parties reject the EU’s minority, migration, and asylum policies feature exclusionary conceptions degrading the substantial meaning of liberal democracy.

More...

Nepal is relatively a new entrant to global labour markets. Nevertheless, over the past few decades, a huge portion of its population has migrated abroad for employment, changing the image of Nepal from a country of “global warriors to global workers” (Rajauriya, 2015). In particular, the political change of 1990 that ushered Nepal into a multiparty democracy triggered the globalizing processes. Unlike during the King’s regime, obtaining passports became easier even for general people, affording them more agility and freedom to travel outside the country (Tiwari & Bhattarai, 2011). Further, the government formed after the 1992 elections embraced a policy of fast-paced economic liberalization, connecting Nepal with global economy and global labour markets (Labour Migration for Employment Report: 2014).

More...

Human mobility is the human face of globalization, the cement that links human communities across the globe and a highly relevant political issue increasingly controversial in many societies in the face of mounting pressures. The main drivers behind human mobility across and within borders are related to the three Ds, Demography and demographic gaps; Development failures and poverty; Democratic and governance failure associated with human rights violations. Moreover, mobility is both a consequence and a cause of human insecurity. On the one hand it is a response to a deregulated globalization that produces increasing inequality and human insecurity but, on the other, mobility itself is increasingly associated with higher levels of human insecurity in the absence of a robust system of international protection.

More...

Sığınmacı ve göçmenlerle sosyal hizmet konusu genellikle kuramsal temellerden yoksun bir müdahale anlayışı ile ele alınmaktadır. Sosyal bilimlerin göçün nedenlerini ve sonuçlarını anlamaya ve göç sürecini şekillendiren ağların ve ulusaşırı toplumsal alanların nasıl inşa edildiğini açıklamaya dönük çabasının sosyal hizmette kuramsal bir karşılığı genellikle yoktur. Sosyal hizmet daha çok sığınmacı ve göçmenlerle çalışmada beceri odaklı bir perspektife sahip görünmektedir ancak müdahale ve beceri odaklı uygulama son çözümlemede kuramsal bir arka plana yaslanmak zorundadır. Sosyal hizmetin uygulamaya olan aşırı vurgusu ve uygulamadan doğan bilgi ve veriyi yeterince teorize edememiş ve düşünümsel bir alan yaratamamış olması göç ve sosyal hizmetin kuramsal temellerine dair etraflı bir çalışmayı mümkün kılmamaktadır. Bu bölümde sığınmacı ve göçmenlere dönük sosyal hizmet uygulamalarının kuramsal arka planı ve temellerine girizgâh niteliğinde bir tartışma yapılmaya çalışılmıştır.

More...

From an Australian perspective, which can be extended to other countries’ migration frameworks, this study raises the notion that “uncertainty” negatively modulates systemic issues in recurring themes of human security violations, fraud and non-integration. Such understanding could lead to insights into migrants’ decision-making processes resulting in the subsequent use of unintended pathways. Literature and case study reviews were undertaken, coupled with a quantitative approach analysing retrospective data from the Department of Immigration and Border Protection and the Australian Federal Police to determine the ineffectiveness of current legislative tools that do not take certainty into account and to determine the impact of uncertainty on migrants in Australia’s migration program as a receiving country. Practical recommendations are presented for consideration by policy-makers to ensure certainty for the migrant, including; to combat human security violations via the provision of visa pathways for applicants to remain after lodging a complaint, ensuring that both employment and human securities can co-exist; to effectively control fraud via the removal of discretion, ensuring certainty in pathways of decision-making processes to combat unintended pathways; and finally, the permeation of certainty throughout the migration program, ensuring that steps to attain citizenship are not out of necessity but instead a step towards successful integration.

More...

This paper aims to disclose the consequences that the system designed by the Catalonian agricultural union “Unió de Pagesos” to recruit, import and distribute foreign labor produces, a subject deprived of its liberties and fundamental rights. Once the model of family farming was substituted by an industrial agricultural system of production, the agricultural union, with the consent of the State, reinvented itself as a provider of services related with the acquisition of manpower through this system - as we designate the set of practices that materialize the recruitment of foreign workers abroad and their concentration is lodgments controlled by the Union. The State’s migration polity is responsible of the emergence of such a system, and we can trace its origin in the symbiotic relation between the State and the union, whose intereststhe social control of the foreign worker and the just in time delivery of labor- are harmonized in it.

More...

The 2015 “migration crisis” has stimulated the European political imagination with an image of migration and border control as based on a mixture of humanitarianism and security. Indeed, the European borders and migratory routes have been increasingly framed in the media and political debates as the sites of a humanitarian and security emergency (see Dekker & Scholten, 2017; Greussing & Boomgaarden, 2017; Ibrahim & Howarth, 2017). The accounts of children dying in the Mediterranean have been reproduced together with images of uncontrollable crowds gathering at the borders, and again with overburdened reception centres with deplorable humanitarian conditions (see BBC, 2018; The Guardian, 2018; Reuters, 2018). All these framings have been (re)merging in the public debate, building a sense of humanitarian crisis, but also insecurity and uncertainty regarding the most suitable course of action at the European level. Regardless the European Union’s (EU) attempts to respond to the increased migratory flows, the humanitarian situation has been getting more severe, generating a political momentum for mobilization of more decisive, security-oriented and even militarized measures in dealing with the crisis. Consequently, the EU has decided to increase its operational and military presence in the Mediterranean with Frontexled Joint Operations (JO) (i.e. Triton, Poseidon and Themis) and Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) naval mission (i.e. EUNAVFOR MED Sophia), explicitly framing the mobilization of security capabilities as search and rescue and “live saving” operations.

More...

In 2015 and 2016, Germany faced an influx of asylum seekers on an unprecedented scale. How did the country react to this so-called “refugee crisis”? The response was a major effort at all levels of the federal state: the federal level, the Länder, the local authorities, but also civil society, welfare associations and NGOs. There have been countless measures in the most diverse fields of action (Grote, 2018). This article will specifically deal with the question of how and which legislative and administrative changes were put in place at the federal level in order to better manage the changing influx.

More...

Since the outbreak of the Syrian Civil War in the spring of 2011, the number of Syrian nationals seeking refuge within the borders of Turkey has surged, and the recent intensified threat of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) has only caused the number of Syrians fleeing to Turkey for safety to rise further. Today, Turkey hosts more Syrians than any other country in the world; according to official United Nations Refugee Association (UNHCR) registration statistics as of April 10, 2015, there are 1,758,092 registered Syrians in Turkey (UNHCR 2015) although estimates among academics, representatives from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and others predict the actual number of Syrians in the country as closer to 2.5 million. However, the legal status of Syrians in Turkey is unique. Not legally recognized as refugees due to Turkey’s historic and current migration policies, Syrians in Turkey are considered as ‘guests’ in the country and remain here under the legal status of temporary protection. Although this status provides for many basic rights - including shelter, food, education, medical support and the possibility of employment - Syrians often remain uninformed of and unable to access their rights-based provisions. Additionally, as the governmental and societal discourse of ‘guests’ suggests, Syrians are expected to be ‘hosted’ by the Turkish government and society and subsequently return home. Although governmental policy and many Turkish humanitarian aid-based NGOs continue to convey this discourse of Syrians as ‘guests’ under temporary protection, Turkish society is becoming tense - the Syrian ‘guests’ have overstayed their welcome.

More...

France has among the European countries one of the longest tradition of receiving immigrants (Freeman, 1994) and was considered for long time as one of the model countries of incorporation of immigrants. France has represented the model called “assimilation”, i.e. the attitude that gives to immigrants all the civic rights very quickly, but in exchange it’s expected that they will give up their cultural particularities and that they will in some sort “forget” from where they come (Seidlová, 2008).

More...