Infantka Anna Katarzyna Konstancja i kultura artystyczno-kolekcjonerska dworu wazowskiego

Infanta Anne Catherine Constance and the Artistic and Collectorship Culture of the Vasa Court

Author(s): Jacek ŻukowskiContributor(s): Author Not Specified (Editor)

Subject(s): Fine Arts / Performing Arts, Architecture, Visual Arts, 17th Century

Published by: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk

Keywords: Princess Anna Catherine Constance Vasa (1619-1651); Philip William of Neuburg; art of the Vasa Court; court celebrations; court ballet; commemorative graphic 17th century; Christian Melich; castrum

Summary/Abstract: Princess Anna Catherine Constance Vasa (1619-51) served as a major link uniting four powerful European houses: the Habsburg and Wittelsbach families as well as the Jagiellons and the Vasas. Revealing new facts about Anna Catherine Constance’s art patronage, the present study also gives a fresh perspective on her iconography and role in the court life of the Polish Vasas, focusing particularly on the performances of court ballet in which she actively participated as a dancer and costume designer. Most emphasis is put on the artistic setting of Anna’s 1642 wedding with Philip William of Neuburg, especially the art collection she had brought from Poland as her dowry. The article concludes with the description of the Princess’s ecclesiastical donations and her funeral ceremony. The frontispiece of the print by Michael Ottonius Becanus presents Anna Catherine Constance as Minerva. Her more conventional likeness in the copperplate engraving by Johann Eckhard and Johann Heinrich Löffler adorned four family trees of the Polish Princess and her husband illustrating the panegyric issued by the Cologne Jesuits, also including a composition with an intriguing view of Kraków. The analysis of the set of portraits the youngest of the Vasas brought with her to Germany provokes reflections on several important issues related to the propaganda message of the collection, which was meant to contribute to shaping her status abroad, as well as to the mechanism of creating respective paintings, this including the role of the portrait costume or style, as well as the relations with the Warsaw court of such painters as Frans Luycx, Pieter Cl. Soutman, or Chrystian Melich. Apart from the set of Persian carpets and items of a more emotional impact (infant portraits, miniatures, etc.), Vladislaus IV gave his sister’s dowry a West European content; what strikes is its high artistic quality and lack of portraits in Polish attire. The dynastic policy promoted by the second Vasa is perfectly illustrated by the reconstruction of the cropped Munich portrait of Cecilia Renata, which originally showed the cradle with her first-born son, newly-born Prince Sigismund Casimir, called the ‘Dolphin.’ The painting was to forecast the revival of the new branch of the Jagiellon House in the person of the expected future ruler of the Polish-Lithuanian state, a possible (also real, not just titular) Swedish king or emperor.Numerous circumstances make one question the thesis that all the Bavarian Vasa-related items are associated with the 1642 dowry of the Princess: some of them are diplomatic gifts, particularly from Sigismund III. Still, the surviving ‘meagre remnants’ (as phrased by M. Gębarowicz) of the famous dowry attest to the quality of the Warsaw court’s material culture, and in particular personal preferences of Anna Catherine Constance, the habitual tableware of the Vasas, as well as the ambitions of Sigismund III, himself involved in handicraft. The above-mentioned patronage and collectorship was based on the idea of a permanent bonding of the Jagiellon tradition with modernity, the unity of the artistic culture of the East and West. The 1642 dowry contained numerous objects engraved and enamelled with the royal coat of arms and monograms confirming their provenance. A peculiar testimony to court customs can be seen in necklaces with medallions, chains, aigrettes, hat bands, and, last but not least, precious jewellery items of allegorical-emblematic connotation. What strikes in the last group are gems that serve the purpose of proto-sentimental sublime courting dialogues, shaped in compliance with the theory of amour courtois – amour honnete (amour précieux), often incorporating interwoven (tied) ‘figures,’ ‘letters’ of the royal fiancées, or spouses, and presented on Name Days, Baptisms, or New Year.The difficult political and financial situation of Philip William forced him to ‘liquidate’ some of the Vasa treasures. Those circumstances did not impede, however, religious foundations. Anna Vasa donated, for instance, goldsmithery utensils and textiles worth several thousand guilders to the court church in Neuburg, as well as paintings of religious topics executed in Poland, and the golden rose, blessed by Pope Paul IV (1607), she had inherited from her mother. In 1642, she founded silver gilded ciboria, decorated with gems from her wedding diadem. On another occasion, she left her wedding dress in the Altötting Marian Sanctuary, of which surplices and antependium were made. Numerous Vasa items were given a secondary function, e.g., the cloth of honour from the ceremonial Vasa baldachin from ca 1605 was reused for amices. Some of the objects were originally diplomatic gifts, for instance the carpet presenting a female winged genius perī, probably brought to the Polish court in 1609 by Robert Shirley, envoy of the Persian Shah. The carpets preserved in Munich are in their majority identical with the items that had been left behind in Warsaw (having been commissioned in pairs), however the latter have all disappeared. The German collection, analogical to the Swedish loot from the Second and Third Northern Wars, played the role of a peculiar capsule temporelle in the context of the Vasa court art.Five days after the Princess’s death in Cologne, her body was exposed to public viewing. Following the completion of the ceremonious exequiae at St Gereon’s Basilica, court officials and numerous Polish noblemen bid farewell to the cortege on the bank of the Rhine. The widowed Prince saw to having a castrum doloris raised in Neuburg; its design, modelled on the ephemeral funeral structure of 1629, was executed by Hans Georg Doctor. Furthermore, two years after the Princess’s death, Paul Bock placed her crypto-portrait (sakrale Identifikationsporträt) in the painting featuring the Assumption of Our Lady in the Neuburg Castle church’s chapel. The disguised portrait may have been modelled on the unpreserved canvas by Joachim von Sandrart, a counsellor at the Neuburg court. That very portrait formed part of the Neuburg Castle portrait gallery, containing numerous portraits of the Polish Vasas, who never ceased to emphasize their European connections and aspirations.

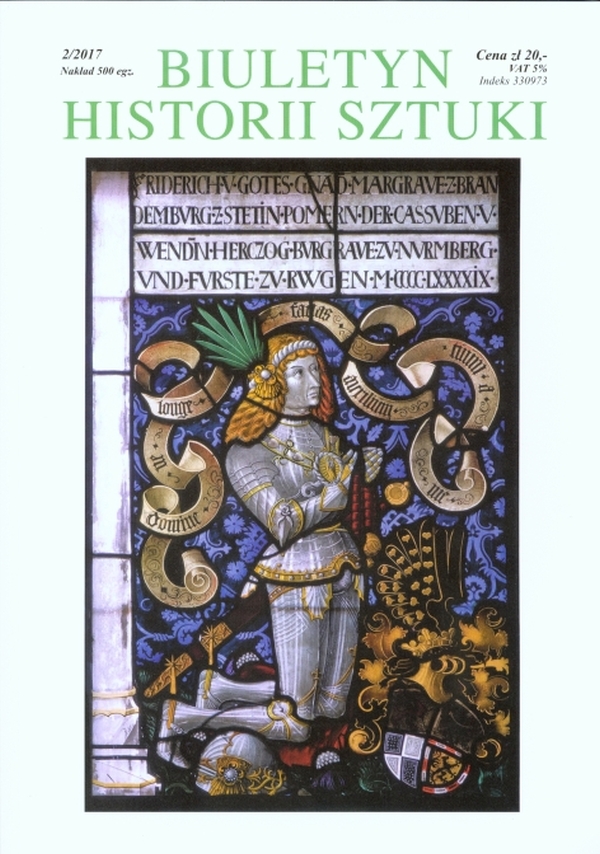

Journal: Biuletyn Historii Sztuki

- Issue Year: 79/2017

- Issue No: 2

- Page Range: 233-312

- Page Count: 80

- Language: Polish

- Content File-PDF