Mokotów (część górna) – maison de plaisance à goût champêtre w tonacji malowniczej

Mokotów (Upper Part): Maison de Plaisance à Goût Champêtre in a Picturesque Tone

Author(s): Jolanta PolanowskaSubject(s): Fine Arts / Performing Arts, Architecture

Published by: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk

Keywords: neo-classical architecture; garden art; picturesque-style buildings; english landscape garden; regular formal garden; jardin naturel; Warszawa (Warsaw); Mokotów suburban residence

Summary/Abstract: Jolanta Polanowska, Mokotów (Upper Part): Maison de Plaisance à Goût Champêtre in a Picturesque Tone Mokotów was a suburban palace and garden ensemble of a regular outlay owned by Princess Izabella Lubomirska née Czartoryski (1736-1816) located on the Vistula escarpment’s edge, with a later wooded part on the slope, and the latest one - almost a separate landscape aquatic section at the foot of the escarpment (see BHS 2013 No. 3). To-date the final facet of the ensemble has been regarded as to have been genuinely planned from the onset, this assumption insufficiently taking into account the long period of its creation and all the introduced changes in its course. The newly discovered archival records as well as the analysis of the written sources regarding the estate-related plans, allow to reconstruct over a decade-long process of acquiring, arranging, and transforming subsequent plots, as well as stylistic alterations of its complex structure.Having been assigned to the Grand Crown Marshal position in 1766, which required his permanent presence in the capital, Prince Stanisław Lubomirski together with his wife chose the terrain on the Vistula escarpment near the village of Mokotów, of fragmented ownership, as the spot for their suburban residence. In 1771-76, following legally complex transactions, they acquired the eastern sections of the plots in question and a part of the slope. In 1771, the plot belonging to the vicars of the Warsaw Collegiate Church of St John was leased, and so were ‘peasant empty fields’ from the Warsaw Starostship, the latter most likely wasteland on the slope and at the marshy foot of the escarpment. In September 1772, as a result of an exchange with the Ujazdów Parish Priest, the plot on the escarpment edge meant for a palace was obtained. The construction of the little palace was commissioned to Ephraim Schröger who outlaid a regular ensemble design with the edifice located at the crossing of the vertical axis and the horizontal one, shifted towards the escarpment. In 1772, the implementation of the whole project began. In 1773-74, the following were completed: the little palace, a regular formal garden with wall trees and two arbours, and a farm. In 1774, the plot located north of the access alley was acquired from the Warsaw Starostship, where the Kitchen Garden was created (as of 1775). On 14 March 1775, the King authorized the takeover of the lease of the Alderman’s Volok, subsequently purchased in January 1776, likely with the landscaped part on the slope in mind. For the latter purpose Simon Gottlieb Zug was employed, who extended it onto the escarpment’s base, later stretching it further onto the terrain purchased from the Augustinian Fathers (1776) as an aquatic part. Simultaneously, in 1776-84, Zug continued intense works in the upper part and on the escarpment slope. Turning its mass into irregular, he altered the little palace. He also raised some asymmetrical functional pavilions - the sumptuous gatehouses: the Flemish Gloriette (1776) and the Dovecote Tower (1780), as well as the Orangery (1779). Additionally, Zug rearranged the garden in front of the little palace and created a wooded section on the slope. Therefore, three stages in giving the estate its final shape can be distinguished, each representing typological stages in the development of its architecture and gardens. Ephraim Schröger’s design is a symmetrical palace and garden ensemble with an access road between two Loges de Concierger, and the Avenue leading to the Grand Cour. The northern elevation of the palace featured an entrance on the axis that formed at the same time the crosswise axis of the residence. The ensemble was outlaid in zones: between the road and the little palace there was the symmetrical axial functional part: Jardin Potager, flanked from the south by the home farm, while from the north by an almost symmetrical gardener’s farmyard. There was a garden with regular ornamental beds in front of the palace. Ephraim Schröger’s design’s implementation. Despite the enlargement of the estate, which implied the changes in the plans, the little palace as such remained (until 1780) in its genuine form. It was a bungalow (actually two-storeyed, with the basement partially sunk in the escarpment), and a partly functional attic; a cubic building, it had five-axes elevations of flat avant-corps and a tent roof. Set on a square outlay, planned axially, with an asymmetrical room arrangement: a reception room from the front, a dwelling apartment behind, the second one on the mezzanine, it featured a bathroom and servants’ quarters in the basement. It was a belvedere and the pavilion of the casino in giardino in geometric gardens: a ‘gala’ one from the front, from the north framed by the fruit and kitchen gardens, whereas from the west there was a flower garden also at the back of the palace. The modernization of the estate by Simon Gottlieb Zug consisted in the palace’s alterations, development of the new plots, and their integration with the old ones, the process blurring the regularity, axiality, and symmetry of the outlay. The alterations of the little palace (and the transfer of certain rooms to separate edifices), consisted in adding some irregular and asymmetrical buildings. The basement witnessed the creation of the bathroom apartment, arranged to resemble a cavern covered with boulders. The transformation of the functional and decorative gardens consisted in covering them with the ‘unifying’, camouflaged however division network. In front of the palace there was an arrangement of six parallel strips that alternately ‘expanded’ the former segments, blurring the regular character of the layout. The new parts were connected with new functional pavilions: the small Orangery with an arched elevation, integrated with the Gardener’s House into an edifice complying with the ‘non-Classical’ trend in the Antique. The brick arbour was replaced by the Gloriette à la Flamande, meant to serve as a belvedere and a gatehouse: it was connected with the pavilion serving as the entrance to the home farm, namely the Gothic Tower with a Dovecote, by means of a smooth wall. The gatehouses and the orangery, placed fan-wise on the viewing axes from the palace, presented the following (from the north): there was the ‘non-classical Antique’ Orangery, the ‘Mannerism’ of the Flemish Gloriette, and finally the ‘Gothic’ character of the Tower. Moreover, Zug ‘extended’ eastwards the functional backstage, while arranging the forest walking section called the ‘Wild Promenade’ on the escarpment and at its foot, putting there a sizeable pond, whereas around and below there was a ‘forest wildly planted’, with a labyrinth of paths, gaining variety thanks to springs, cascades, caves, and arbours. The novelty Zug introduced consisted in blurring the regular classical rigorous composition created by his predecessor. Ridding the palace’s mass of symmetry, axiality, and the regular character, made it more picturesque; the abandoning of the decorum principle: irregular masses in historicizing costume of functional pavilions, bestowed upon it the ornamental function. Emphasizing of the innovatory masses was the application of the decorum rule to the composition, which, also thanks to the pavilions’ silhouette, eye catchers, integrated the lower and upper part by means of viewing axes. When in Paris, Princess Izabella Lubomirska, fan of the Louis XIV’s era, visited new trendy ensembles, including the maisons de plaisance à goût champêtre near Paris. Her interest in L’Hermitage of Marquise de Pompadour in the Petit Trianon is confirmed by the purchased design with the plan: ‘CARTE / DE L’HERMITAGE / DE MADAME / DE POMPADOUR / A VERSAILLES’. In Mokotów a similar programme was implemented with the similarity to be found also in the type of a single-storey five-axes palace. Furthermore, similarities with the Fontainebleau L’Hermitage of the Marquise de Pompadour can be traced, particularly in the small, cubic, scantly decorated little palace of the casa di villa type with decorative poultry husbandry. All the three displayed the champêtre, namely ‘rural decorative’ style. The Mokotów village featured the remains of an old local manor from the 16th century where in the summer of 1611 Sigismund III’s prisoners were kept, i.e. Tsar Vasili and his brother Prince Dmitry Shuisky; a fire broke out then, destroying a part of the building. Tradition has it that the manor walls were used as foundations for the Princess’s palace. Of importance were also the traces of the former neighbourhood from the times when a part of the Mokotów Alderman’s Volok had been owned by the Princess’s great-grandfather Stanisław Herakliusz Lubomirski (1641-1702) who had had Tylman van Gameren (1632-1706) extend the Ujazdów Park ensemble onto its vicinity. The fragment of van Gameren’s water supply system, recreated by Zug, and praised by S.H. Lubomirski in the poem Arcadia, alias a Pastoral House near Mokotów (today close to Królikarnia), transporting water to the Ujazdów Bath (Łazienka) traversed the Princess’s lower garden as a navigable section of the water network connecting Mokotów and the King’s Baths (Łazienki). Moreover, both palaces were linked by a viewing axis, whereas the concept of the Princess’s cavern bathroom possibly reflects the inspiration of the Cavern Bathroom in the Palace on Water (before 1683). Meanwhile, the figure of Thetis echoes the famous Versailles pavilion La grotte de Téthys. Furthermore, the Princess, drawing inspiration from Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s ideas, did not only dedicate the lower garden to him, but also decided to alter the style of the upper part, turning it into the jardin naturel type. The fashion for English garden also came from France; within the King’s circle it was August Fryderyk Moszyński who presented it in his Essay sur le Jardinage Anglois (1774), being an adaptation of Thomas Whateley’s Observations on Modern Gardening (London 1770, after the translation by François de Paule Latapie, L’art de former les Jardins Modernes, ou l’art des Jardins Anglois, Paris 1771), illustrated by Simon Gottlieb Zug. Moszyński mentions Mokotów as one of the estates on the Vistula escarpment that his essay was meant for. Hence in the plan certain solutions he suggested can be pointed to. Furthermore, Zug could derive some common models from pattern books, e.g. William Chamber’s plans for Kew Gardens (1763). More genuine architectural forms were elaborated for gatehouses, whose models may have been picked by the Princess (see below). Mokotów was shaped as a result of overlapping French and English influences. The reception of ‘fashionable models’ was fast: almost 25 years’ earlier Hermitage of Madame de Pompadour, some dozen years’ earlier influences of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s circles, and an almost parallel adoption of the English garden principles thanks to Moszyński’s adaptation (1774). Around 1775, the decision was made to alter the newly built Neo-Classicist regular ensemble and the necessary plot was purchased in order to transform it together with the palace following the picturesque style as of 1776.In the ideological programme, circles of constant ideas were present: profound agronomic knowledge, ‘picturesque rustic character’, the combination of cognitive verism and natural history, with a sentimental attitude to nature grounded in Rousseau’s ideas, as well as personal and family references. The idea of creating her own fashionable country retreat amidst a model farm was related to certain agronomic interests the Princess nurtured, the latter testified to by some guidebooks in her book collection. The family motif can be traced in the Princess’s concept of the gate pavilions echoing mediaeval buildings. The name of the ‘Flemish Gloriette’, emphasized in Zug’s description, may have been a reference to the Borculo Castle (today Berkelland) in Gelderland, the Netherlands, inherited by her sister-in-law Izabela Czartoryska née Flemming. Both structures, namely the Borculo Castle and the Flemish Gloriette, were solid masses with a narrow turret (embedded in the corner). When searching for a contrasting form for the second gatehouse, Zug may have found inspiration in a different building in Gelderland, namely the tower of the Romanesque – Gothic Hochwasser Church in Roermond. In compliance with the allusive garden principles, the garden being a peculiar sort of a charade, the pointed formal and content associations should be clear to the public. The coincidence of content motifs, expressing the Princess’s convictions and sentiments, and reflected in Zug’s forms, constituted Mokotów’s ciphered message. It was both the Prince and the Princess who initiated the creation of the residence, while the Princess was the source of ideas: she authored the functional, ideological, and partly formal programmes, while also having the final say on their implementation. What strikes is the extent of her efforts to acquire the selected plots. The project was first designed and implemented by Ephraim Schröger, Simon Gottlieb Zug only taking over after him. The important though hard to pinpoint, and to-date underestimated role was played by the promoter of the English landscape garden August Fryderyk Moszyński. Mokotów, a multi-style work, was created for an ambitious person of refined taste that the Princess was; thanks to her being snobbish and following the Paris fashion, as well as thanks to the mastery of excellent architects, it was an extremely elitist work, a next-to contemporary ‘style transfer’. Accelerated perception resulted in contaminating function, form, and content. Physiocracy was combined with a cognitive and sentimental attitude to nature; while curiosity about the works of old art found expression in picturesque-style buildings within the trend of associative historicism. Mokotów, being a pioneer work, was introducing the picturesque style to Warsaw’s architecture.

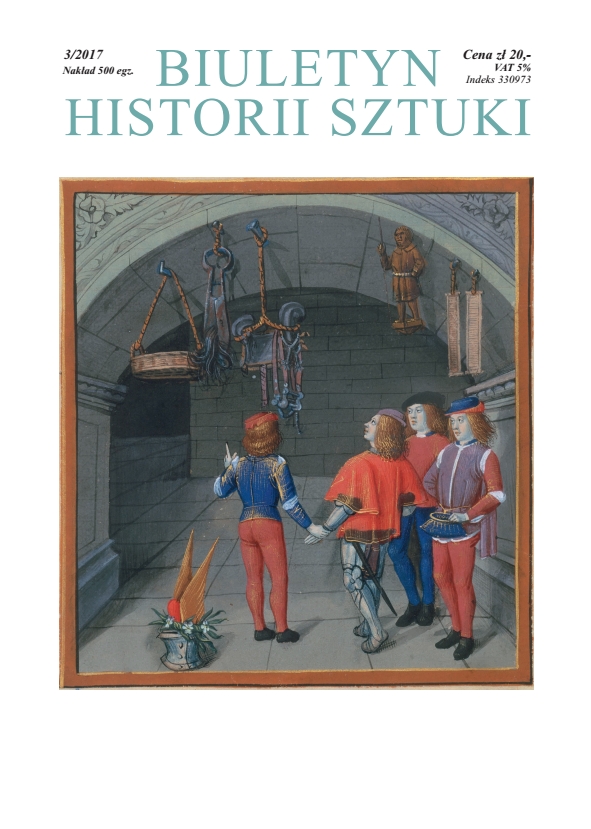

Journal: Biuletyn Historii Sztuki

- Issue Year: 79/2017

- Issue No: 3

- Page Range: 471-508

- Page Count: 36

- Language: Polish

- Content File-PDF