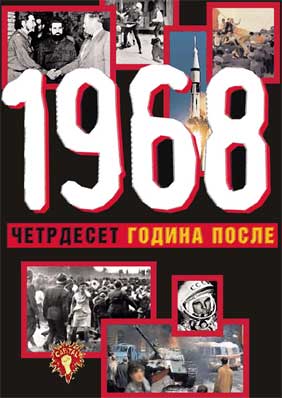

1968 - четрдесет година после

1968 Fourty Years Later

Contributor(s): Radmila Radić (Editor), Ljubodrag D. Dimić (Editor), Milan Ristović (Editor), Dragan Bogetić (Editor), Aleksandar Životić (Editor)

Subject(s): History, Cultural history, Diplomatic history, Economic history, Political history, Social history, Recent History (1900 till today), Special Historiographies:, Post-War period (1950 - 1989), History of Communism, Historical revisionism, Cold-War History

Published by: Institut za noviju istoriju Srbije

Keywords: Prague Spring; Student Demonstrations in 1968; Socialism; Eastern Europe; Soviet Intervention in Czechoslovakia in 1968; The Yugoslav People’s Army;

Summary/Abstract: 1968 – Forty Years Later represents a collection of historiographical works of 26 authors from different countries (Serbia, Russia, Czech, Croatia, Bulgaria, and Germany) about the international relations and the foreign-relation temptations of Yugoslavia and also about the domestic circumstances in Yugoslavia during the years 1967-1969. The first part of the book is dealing with topics like: 1968 as the turning-point for Eastern Europe, „Prague Spring“ after the increase of Soviet pressure on Czechoslovakia (July 1968), „Prague Spring“ and the attitudes of the Hungarian leadership, its influence in Bulgaria, the phenomenon of the Czechoslovak opposition after the defeat of the „Prague Spring“ in 1969-1972, the year 1968 as a point of departure of the new Yugoslav foreign policy orientation, Yugoslav reactions to the crisis in the Middle East and dictatorship in Greece, Yugoslav-Soviet, Yugoslav-Romanian and Yugoslav-Italian relations in the days of the Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia relations with the Federal Republic of Germany in 1960s, Yugoslav economic emigration in West Germany and the visit of the crew of Apollo 11 to Yugoslavia in 1969. The second part of the book is consisted from the works about Yugoslavia's activities in domestic and foreign policy after the intervention of the Warsaw Pact in Czecholsovakia in 1968, Yugoslav People’s Army’s ordeals in 1960s, the echo of the global student revolt of 1968 in Yugoslav youth and student press, student demonstrations in Belgrade and Yugoslavia in 1968, the case of Krunoslav Draganovic as one aspect of Yugoslav − Vatican relations, liberalization of Yugoslav theatre, and „rebellious“1968 in Istria. Most works are based on the new historical researches and they, after forty years, try to give a new answer and point of view on the issues connected with the happenings in 1968. The book contains also Chronology of the important events in 1968 and Bibliography of the selected Works on 1968.

- Print-ISBN-13: 978-86-7005-063-1

- Page Count: 738

- Publication Year: 2008

- Language: Serbian

Подаци о ауторима

Подаци о ауторима

(Notes on Contributors)

- Author(s):Author Not Specified

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Essay|Book Review |Scientific Life

- Page Range:15-20

- No. of Pages:6

- Summary/Abstract:Notes on Contributors

- Price: 4.50 €

1968. година – повратна за Източна Европа

1968. година – повратна за Източна Европа

(The Year 1968 – The Turning-Point for Eastern Europe)

- Author(s):Iskra Baeva

- Language:Russian

- Subject(s):Cultural history, Military history, Political history, Social history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989), Historical revisionism, Cold-War History

- Page Range:27-50

- No. of Pages:24

- Summary/Abstract:The year 1968 was one of crisis, both for Eastern and Western Europe. There was a similarity in student-riots (in France, Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia), but mutual differences were much greater. An attempt at revamping the social system which had been established after WWII under Soviet influence was made in Eastern Europe in 1968. The new leadership of the Czechoslovak Communist Party, headed by Alexander Dubček undertook a reform with the goal of making the state socialism more democratic, in order to weld social security with human rights („socialism with human face”). In connection with reforms in the neighboring Czechoslovakia, Polish students stood up to protect intellectual freedoms. However, the government managed to stir up anti-intellectual and anti-Semitic sentiments and supress the dissatisfaction. Władisłav Gomułka came out against reforms. The changes in Czechoslovakia – abolition of censorship, preparation of the Action program with the aim of making socialism more democratic, economic reforms of Oto Šik – led to troubles in the relations between the countries of the Eastern Bloc. At meetings in Dresden (March 23), Moscow (May 8) and Warsaw (July 14–15), the leaders of the Warsaw-Pact countries increasingly criticized Czechoslovak reforms and demanded increasingly more determined that they be rescinded. Finally the danger of a reformist spill-over led to the decision to intervene militarily in Czechoslovakia on August 21, 1968. The military intervention changed the relations in Eastern Europe. Yu goslavia and Romania felt endangered and they reacted sharply. The suppression of the ”Prague Spring of ‘68” influenced mostly the attitudes of Eastern Europeans. They realized the preservation of the system and power was more important in the Eastern Bloc than the interests of the society.

- Price: 6.00 €

Југославија и блискоисточна криза 1967–1968. године

Југославија и блискоисточна криза 1967–1968. године

(Yugoslavia and the Crisis in the Middle East in 1967–1968)

- Author(s):Aleksandar Životić

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Diplomatic history, Military history, Political history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989), Historical revisionism, Cold-War History

- Page Range:51-67

- No. of Pages:17

- Summary/Abstract:The crisis in the Middle East in 1967 left extremely durable marks not only on the relations in the Middle East, but also on global international relations. The vehemence of the conflict between Israel and the Arab nations caused the reaction not only of the countries from the region and both super-powers, but also of other major powers and smaller countries, particularly the non-aligned ones. As a non-aligned country with a tradition of very close ties with Arab countries, Yugoslavia took an active part in the events caused by the brief Third Israeli-Arab war in which the armies of the Arab nations had been routed. Ever since the crisis started, the Yugoslav administration reacted swiftly, participating in a number of actions aimed at helping the Arab countries and alleviating the consequences of the disastrous defeat of their armies. The Yugoslav diplomacy was particularly active in evacuation of the Yugoslav Blue- Helmet contingent stationed in Sinai, which was successfully done. Considerable military and economic aid was sent to the Arab countries. In the diplomatic field Yugoslavia advocated the interests of the Arab nations, insisting on a compromise solution – which at certain point led to a brief cooling of the Yugoslav-Arab relations caused by the rigidity of the Arab nations. The Yugoslav attempt at diplomatic mediation was based on day-to-day contacts with great powers, with an attempt at broader and more versatile engagement of the non-aligned countries with the aim of strengthening the position of the Arab countries. However, the crisis in the socialist world in 1968 and the aggravation of the conflict in the Far East, particularly the war in Vietnam, coupled with the transition of the process of solving the Middle East crisis into a slower, negotiatory phase, caused the Yugoslav diplomacy to show less interest in the removal of the consequences of the Middle East crisis.

- Price: 6.00 €

Година oпрезног испитивања: Југославија и диктатура у Грчкој у 1968. години

Година oпрезног испитивања: Југославија и диктатура у Грчкој у 1968. години

(The Year of Cautious Examination: Yugoslavia and the

Dictatorship in Greece in 1968)

- Author(s):Milan Ristović

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Diplomatic history, Military history, Political history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989), Cold-War History

- Page Range:69-96

- No. of Pages:28

- Summary/Abstract:The coup d’etat which was organized and executed with no particular difficulties by a group of army officers in Greece on April 21, 1967, headed by a „triumvirate” comprising two colonels, Georgios Papadopoulos and N. Makarezios, and a brigade general, Stulianos Patakos, was the culmination of a long political crisis, conflicts and enmities of leading political figures and their parties, the court and the Army. The imposition of military dictatorship dramatically contributed to deterioration of Yugoslav-Greek relations which were experiencing upturn until the spring of 1967. Strong anti-Communist orientation of the colonels’ regime and repression of political dissenters, particularly on the left, the use of propaganda slogans from the days of the civil war, coupled with annulment of some bilateral treaties previously concluded with the Yugoslav government, by the end of 1968 caused the relations between Belgrade and Athens to pass from the period of almost total political freeze in the beginning, to gradual, cautious sounding and eventually to the degree when they were brought to a level of restrained normalization. Such state of affairs, with occasional deteriorations and rapprochements, would last until the fall of the junta in 1974. The difficult relations between Belgrade and Athens during 1967–1968 (and later on until the end of the dictatorship) were analyzed in the context of the general deterioration of the international situation (Israeli-Arab war, the military intervention of the Warsaw Pact in Czechoslovakia, beginning of the new phase in the Cyprus-crisis, escalation of the war in Vietnam). They should also be seen as part of the Cold War, in which Yugoslavia played a particular, untypical role. Caution, restraint and careful deliberation about every move which the Yugoslav diplomacy made in connection with the colonels’ regime, were typical both for the beginning of the colonels’ regime in Greece and for the later years. Clear and overt disagreement with the dictatorship was mingled with frequent pointing out at the fact that Greece was a neighbouring country with whose internal affairs one shouldn’t interfere. Such an attitude didn’t mean complete passivity; parallel with significantly reduced relations with the Athens government, the Yugoslav side maintained ties with the Greek opposition, both with its members working in the country under difficult conditions, and with its most prominent leaders and groups of various ideological persuasions who waged their struggle to topple the dictatorship from exile. These relations were also a sign of the understanding that the colonels’ dictatorship was just a transient phase and that the opposition leaders in exile (K. Karamanlis, A. Papandreou) should be considered representatives of continuity, including the full reestablishment of bilateral relations that would be re-established once the dictatorship was brought down.

- Price: 6.00 €

Jugoslavija i Praško proleće posle pojačanja sovjetskog pritiska na Čehoslovačku (jul 1968)

Jugoslavija i Praško proleće posle pojačanja sovjetskog pritiska na Čehoslovačku (jul 1968)

(Yugoslavia and the „Prague Spring” after the Increase of Soviet Pressure on Czechoslovakia (July 1968))

- Author(s):Jan Pelikán

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Diplomatic history, Political history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989)

- Page Range:97-128

- No. of Pages:32

- Summary/Abstract:For quite a while Belgrade kept a rather guarded, more or less passive, attitude toward the „Prague Spring”, both in the international arena and in domestic policy. It was only around July 10th that the character of the relations of the two countries suddenly started to change. The Yugoslav leadership was alarmed at the news of threats of five Warsaw Pact countries to Dubček’s government and the information of real danger of Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia. The Belgrade government decided to intensify its contacts with Prague. At first it wanted to send Krste Crvenkovski to Prague. The leadership of the Czechoslovak Communist Party proposed that Josip Broz Tito also visit Czechoslovakia. At the same time, it condemned Soviet threats to the „Prague Spring”. The leadership of the Czechoslovak Communist Party accepted the Yugoslav proposal with gratitude. For the first and the last time during the „Prague Spring” representatives of reformist part of the „Prague Spring” considered closer cooperation with Tito’s regime between July 10th and 20th July. They even toyed with the idea of Czechoslovakia opposing the Soviet pressure in the same way Yugoslavia had done in 1948. However, deliberations about closer collaboration with Yugoslavia were just an episode in the short history of the „Prague Spring”. After the agreement with the leadership of the KSSS in Čierné nad Tisou about negotiations between the two parties, the interest of Dubček’s regime for cooperation with Yugoslavia soon died down. Tito’s leadership also didn’t consider support for the reformist processes in Czechoslovakia to be the priority of its foreign policy. It criticized Soviet pre ssure on Prague both for fear it could spill over to Yugoslavia, and because it wanted to preserve at home and abroad the image of Yugoslavia as a freedom-loving country which consistently opposed the practice of great powers in international relations. On the other hand, Belgrade had no interest in spoiling relations with Moscow. The reforms in Czechoslovakia have already in many respects gone be yond those introduced in Yugoslavia throughout twenty years since the break with Stalin. Tito’s regime feared the possible success of the Czechoslovak reforms could destabilize the situation in Yugoslavia.

- Price: 6.00 €

Југословенско-совјетски односи у светлу војне интервенције у Чехословачкој 1968. године

Југословенско-совјетски односи у светлу војне интервенције у Чехословачкој 1968. године

(The Yugoslav-Soviet Relations in the Light of the Military

Intervention in Czechoslovakia in 1968)

- Author(s):Dragan Bogetić

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Diplomatic history, Political history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989)

- Page Range:129-161

- No. of Pages:33

- Summary/Abstract:The military intervention of five Warsaw Pact countries in Czechoslovakia in 1968 led to sudden deterioration of the Yugoslav-Soviet relations and called for the revamping of Yugoslav foreign-political strategy. Fearing the rerun of the Czechoslovak events on the streets of Belgrade, Tito and his aides in their increasingly frequent public speeches severely criticized Moscow’s policy toward Czechoslovakia, expressing their unfaltering determination to defend the independence of their country with all means, should it be endangered. They estimated that the future approach of the USSR to Yugoslavia would directly depend on Soviet assessment of the internal situation in Yugoslavia and the behaviour of Western powers in the case of possible Soviet attack on Yugoslavia. Neither seemed encouraging. Mass student demonstrations and increasingly fierce frictions among the Yugoslav republics, were assessed as factor which could encourage Soviet officials to intervene in Yugoslavia. The extremely mild reaction of the USA to the aggression on Czechoslovakia was similarly assessed. Such a reaction was explained in the Belgrade political circles as the possible consequence of American-Soviet deal on division of spheres of interest in Europe, with Yugoslavia falling into the family of socialist, pro-Soviet states, and thus a possible object of „brotherly aid of the USSR”, lent with the aim of preserving the endangered achievements of socialism. However, the mutual interest forced Yugoslav and Soviet offi cials to reach a mutually acceptable compromise. It boiled down to a simple political formula, agreed upon at the meeting between Tito and Gromiko at Brioni in September 1969. The Yugoslav side agreed to stop its anti-Soviet campaign over Czechoslovakia and Soviet endeavours to discipline its camp, and the Soviet side agreed to stop attacking „Yugoslav revisionism” and to create condition for realization of previously signed economic treaties, desperately needed for improving the disastrous situation of the Yugoslav economy. Although the immediate danger of Soviet intervention in Yugoslavia receded, spectres of Soviet interference into internal developments in the country never completely left minds of political circles in Belgrade. The persistently reiterated demands of Soviet offi cials throughout the period that followed (until the break-up of the Yugoslav state): that Yugoslavia allow access to the Soviet navy to her Southern ports, to join consultations of communist parties, to finally agree to the founding of the Society of Yugoslav-Soviet Friendship in Belgrade, to adjust its model of development to those of other European socialist countries, and in a word, to become part of the Soviet bloc – additionally confirmed justifi ability of Yugoslav fears that close ties with the USSR would necessarily lead to erosion of the key principles of Yugoslav foreign policy and to her final subjection to commands from Moscow. Tito found the way out from the difficult situation in gradual opening toward the South and in creation of a movement comprising states which, like Yugoslavia, permanently oscillated between the East and the West, searching for their identities lost in an inexorable bipolar world.

- Price: 6.00 €

Југословенско-румунски односи у данима совјетске интервенције у Чехословачкој 1968. године

Југословенско-румунски односи у данима совјетске интервенције у Чехословачкој 1968. године

(Yugoslav-Romanian Relations in the Days of the Soviet

Intervention in Czechoslovakia in 1968)

- Author(s):Vladimir Lj. Cvetković

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Diplomatic history, Political history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989), Cold-War History

- Page Range:163-179

- No. of Pages:17

- Summary/Abstract:The crisis which started with the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Soviet, Polish, East-German Hungarian and Bulgarian troops on August 21. 1968, influenced Yugoslav-Romanian relations too. Although the Czechoslovak crisis was globally the „topic of the day” and left its mark on the overall international relations of those days, it seems it had special significance for Yugoslavia and Romania and their mutual relations. That significance laid above all in the fact that refusal to take part in the joint action of the countries of the Warsaw Pact (the member of which it was) in Czechoslovakia, was the point of greatest and most audacious divergence of Romania from the Soviet Union and other East European countries, members of the Warsaw Pact and the Comecon, which came about as the result of the process of gradual and cautious emancipation from the Soviet political and economic domination, that had been going on from mid-1959s. At the same time, the situation created by the Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia in the period that immediately followed, with the atmosphere of increasingly strained relations of both countries with the Soviet Union and other socialist countries which lent support to the intervention in Czechoslovakia, brought the Yugoslav-Romanian relations to the peak of rapprochement, which was refl ected in frequent contacts on the highest, as well as on lower diplomatic levels. Thus the final result of Romania’s distancing from the Soviet Union, the Warsaw Pact and the Comecon, was at the same time the peak of rapprochement with the neighboring Yugoslavia. Therefore the Yugoslav-Romanian relations in the days after the Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia had a double significance for Yugoslavia. On the level of bilateral relations, the crisis helped Tito during his talks with Ciauşescu in Vršac on August 24, 1968 to define, the framework of Yugoslavia’s future support for Romania’s „independent way”, limiting thus the „intimacy” of the Yugoslav-Romanian embrace. On the other hand, on the level of Yugoslav-Soviet relations, Tito’s influence on Romanians to ease tensions, made it possible for him to send the signal to the Soviets that, despite all differences and ideological divergence, Yugoslavia wasn’t willing to effectively support desires of a member of the Soviet bloc to leave Moscow’s fold.

- Price: 6.00 €

„Пражская весна” 1968 г. и позиция руководства Венгрии

„Пражская весна” 1968 г. и позиция руководства Венгрии

(„The Prague Spring” of 1968 and the Attitudes of the Hungarian Leadership)

- Author(s):Aleksandr S. Stikalin

- Language:Russian

- Subject(s):Diplomatic history, Political history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989), Historical revisionism

- Page Range:181-213

- No. of Pages:33

- Summary/Abstract:The Hungarian communist leader Janos Kadar who launched limited economic reforms in his country since January 1968 assessed the moderate reform-communists in Czechoslovakia as the potential allies in his desire for certain modernization and rationalization of the socialist economics in Eastern Europe. Realizing the negative attitude in Kremlin to the ideas of Prague reformers, the Hungarian leader attempted to be the mediator between the Soviet and Czechoslovak communist leaderships. He tried to persuade Brezhnev and the members of his team that the reformist plans declared in Czechoslovakia would not threaten the Communist power in the country and therefore the Soviet interests. On the other hand, he called the Czechoslovak colleagues to more discretion and more attention to the interests and anxieties of the USSR. In mid-June when the Czech literary weekly published the article marking the 10-th anniversary of the execution of Imre Nagy, Kadar corrected his attitude towards the events in neighbor Czechoslovakia. He was sure that the Dubček leadership was losing control over the political processes, and that there was a real danger that the developments in Czechoslovakia would get the form similar to the developments of the Hungarian crisis in 1956. Nevertheless, Kadar tried to influence further both the Czechoslovak and the Soviet colleagues to meet and he pretended still to be the mediator between Moscow and Prague. Even in August, he preferred the peaceful solution of the conflict but did not dare oppose the joint military action implemented on August 21, 1968. His choice was in accordance with the priorities of Kadar’s foreign policy. The Hungarian leader avoided threatening the normal relations with the USSR for he was sure that they were the main guarantee of more independent and fruitful internal policy. The „Prague Spring” revealed the limited possibilities of Kadar’s regime to pursue more active foreign policy without running the risk of undesirable complications with the USSR.

- Price: 6.00 €

„Пражката пролет” – 1968 г. и някои аспекти на нейното отражение в България

„Пражката пролет” – 1968 г. и някои аспекти на нейното отражение в България

(„The Prague Spring” of 1968 and the Influence of Some of its Aspects on Bulgaria)

- Author(s):Vladimir Migev

- Language:Bulgarian

- Subject(s):Cultural history, Diplomatic history, Political history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989), Cold-War History

- Page Range:215-228

- No. of Pages:14

- Summary/Abstract:Important liberalization of the regime in Bulgaria in early 1960s increased the interest of Bulgarian intelligenzia for Czechoslovakia. Bulgarians were particularly impressed by films about „the Czech wonder in the cinema” which showed a new freedom-loving spirit which had already gained ground in Czechoslovakia. With the beginning of the „Prague Spring”(January 1968) the authorities imposed a total informational „blackout” about events in the brotherly Slavic country. Tendentious and „debunking” materials against the „Czechoslovak revisionists” became more frequent during spring and summer. However, the Bulgarian public found ways to get information about the real state of affairs, mainly by listening to Western and Yugoslav radio stations. The days of the „State Security” showed that the majority of Bulgarians, particularly the young and students, reacted positively to the „Prague Spring”. Due to the large influx of unoffi cial information, the government was forced to report, albeit on a limited scale, about the struggle of Czechs and Slovaks against the occupiers after August 21.

- Price: 6.00 €

Социализм против социализма: феномен чехословацкой оппозиции после поражения Пражской весньи. 1969–1972. гг

Социализм против социализма: феномен чехословацкой оппозиции после поражения Пражской весньи. 1969–1972. гг

(Socialism vs. Socilaism: The Phenomenon of the Czechoslovak Opposition after the Defeat of the „Prague Spring” 1969–1972)

- Author(s):Ella Grigoyevna Zadorozhnyuk

- Language:Russian

- Subject(s):Political history, Social history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989), History of Communism, Historical revisionism, Cold-War History

- Page Range:229-258

- No. of Pages:30

- Summary/Abstract:The phenomena of the Czechoslovak opposition after collapse of the Prague Spring, genesis of its ideological and program goals in 1969-1972, when antireform part of the Communist party of Czechoslovakia began repression against the opposition, were analyzed in this article. The representatives of conservative course were victorious and the Prague Spring party’s programs and documents were canceled as „erroneous” (revisionist or opportunist). Opposition demonstrated their adherence to the democratic socialist ideas and this was the main paradox of the movement. The difference was shown within the framework of this movement and it was reflected in formation of some organization trends of the movement - The Movement of revolutionary youth (MRY), The Socialist movement of the Czechoslovak citizens (SMCC) and the Czechoslovak movement for the democratic socialism (CMDS). In general their activities were characterized in this period by double removal of the centers of the opposition’s movement - firstly, from the legal to illegal forms and secondly, from ideology of „socialism with human face” to the ideology of human rights. Confrontation between socialists (Czechoslovakia was named socialist republic) and democratic trends (including ex-communists), who composed the main part of the opposition, was fi nished after their arrests in January and political processes in summer 1972. After this, the Czechoslovak opposition began the search for the new alternatives, in which the socialist ideas did not occupy such important place and the search for new forms such as dissident movement.

- Price: 6.00 €

Полуслужбено партнерство – Југославија и Савезна Република Немачка шездесетих година XX века

Полуслужбено партнерство – Југославија и Савезна Република Немачка шездесетих година XX века

(A Semi-official Partnership: Yugoslavia and the Federal

Republic of Germany in 1960s)

- Author(s):Zoran Janjetović

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Diplomatic history, Economic history, Political history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989), Historical revisionism, Cold-War History

- Page Range:259-274

- No. of Pages:16

- Summary/Abstract:The paper deals with the relations of Yugoslavia with West Germany in 1960s. It gives a survey of these relations in the previous decades and concentrates on their development particularly since the official breach of diplomatic relations in 1957. Political questions (such as indemnification for victims of Nazi persecutions or quasi-medical experiments, recognition of the German Democratic Republic), economic cooperation (credits, trade, tourism, „gastarbeiters”) and extreme anti-Yugoslav political emigration are dealt with. The paper embeds these matters in a broader context of international relations. The article is based on Yugoslav and German archival sources and relevant literature but it does not propose to be more than just a sketch of rich and variegated relations between the two countries.

- Price: 6.00 €

Брантова источна политика и југословенска економска емиграција у СР Немачкој

Брантова источна политика и југословенска економска

емиграција у СР Немачкој

(Brandt’s Eastern Policy and the Yugoslav Economic

Emigration in West-Germany)

- Author(s):Vladimir Ivanović

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Diplomatic history, Economic history, Political history, WW II and following years (1940 - 1949), History of Communism, Historical revisionism, Cold-War History

- Page Range:275-292

- No. of Pages:18

- Summary/Abstract:Accession of the Grand Coalition marked the change of the direction of West-German foreign policy. The main actor, Willy Brandt started giving up the former guiding principles of foreign policy and began the process of normalization of relations with the countries of the Soviet bloc, accepting the reality of the existence of two German states in the process. The new course affected the relations between Yugoslavia and West-Germany too. The two countries reestablished diplomatic relations on January 31, 1968. This was the main precondition for solving problems burdening the bilateral relations. The author analyzes the matter of regulation of the status of the Yugoslav labor force in the FR of Germany and how the new Eastern policy of the new German government and the reestablishment of diplomatic relations influenced the solution of one of the most important problem of the bilateral relations. The solution of this problem encouraged both parties to believe that other problems encumbering the relations of the two countries could also be solved, above all the one concerning indemnification of the victims of Nazi persecution.

- Price: 6.00 €

Југословенско-италијански односи и чехословачка криза 1968. године

Југословенско-италијански односи и чехословачка криза 1968. године

(The Yugoslav-Italian Relations and the Czechoslovak Crisis

in 1968)

- Author(s):Biljana Mišić Ilić

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Diplomatic history, Economic history, Political history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989), History of Communism, Cold-War History

- Page Range:293-312

- No. of Pages:20

- Summary/Abstract:The crisis in Czechoslovakia greatly influenced the development of political and economic relations between Yugoslavia and Italy. Yugoslavia’s disagreement with the policy of the USSR and her condemnation of the military intervention removed any doubt as to the independence of her foreign policy and spurred Italy to change her policy toward the official Belgrade which had hitherto been marked by reserve and distrust. Furthermore, Italy started regarding her relations with Yugoslavia from the point of view of her own security. This opened the way for improvement of relations between the two countries, so that Italy and Yugoslavia tried to demonstrate by a number of activities, the policy of goodneighborly relations and cooperation. After the August events in Czechoslovakia and the danger the USSR could militarily intervene in Yugoslavia too, Italy started lending support to the official Belgrade through numerous public and secret statements of her state officials. At the same time, she launched initiatives to solve unsolved questions in bilateral relations, such as drawing the definitive borderline. In the field of economy she tried to help Yugoslavia in her negotiations with the European Economic Community concerning export of some Yugoslav commodities to the countries, members of the Community. The new course of Italian policy was welcomed in Yugoslavia, due to the importance of this country for the Yugoslav state. Therefore the official Belgrade tried to use the propitious attitude of Italy to solve numerous matters concerning bilateral relations, particularly those from the sphere of economy.

- Price: 6.00 €

Комадић Месеца за друга Тита (Посета посаде Апола 11 Југославији)

Комадић Месеца за друга Тита (Посета посаде Апола 11

Југославији)

(A Small Piece of Moon for Comrade Tito (The Visit of the Crew of Apollo 11 to Yugoslavia))

- Author(s):Radina Vučetić

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Cultural history, Diplomatic history, Political history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989)

- Page Range:313-338

- No. of Pages:26

- Summary/Abstract:The space race between the USA and the USSR which had started with the launching of artificial satellite Sputnik in 1957 and which was continued by the founding of the American National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in 1958 marked 1960s. The Moon became the goal of the belligerent parties in the Cold War, which had to prove scientific, technical, ideological and political supremacy of one of the super-powers. The winner of this race was decided by the success of the American mission Apollo 11 and landing of the first man on the Moon. Aware of global success of their enterprise, the USA wanted to use propagandistically, as good as possible, the fame of their astronauts. For that reason, soon after the return of Apollo 11 it was decided that the astronauts go on a world tour, during which they visited 22 countries between September 29 and November 5, 1969. Yugoslavia was the only communist country they visited (between October 18 and 20, 1969) during this tour, and the behavior of the Yugoslav officials and enthusiasm of the masses in contact with the astronauts, showed that in balancing between the East and the West, when space was in question, Yugoslavia was inclined to the American side. The matter of cooperation with the USA in the field of space research, in which Yugoslav scientists would also take part in the NASA program of satellite observation, was opened already in March 1966. Even before the success of Apollo 11 American orientation in the space race was perceptible in the writing of the Yugoslav press, which started emphasizing the importance of American endeavors to conquer the Moon, even before the American flag was hoisted there. The fact that Yugoslav president Tito, together with Romanian president Ceausescu, was the only chief of a socialist country who was put on the list of the chosen world leaders, whose statements, together with statements and messages of Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon and messages of 73 world leaders were recorded on adisc the astronauts left on the Moon, testifies to Yugoslav sympathies for America in the space race. The extraordinary publicity of the success of the mission of Apollo 11 in the Yugoslav public culminated during the astronauts’ visit to Yugoslavia. Although the press emphasized that the American success was an achievement for the whole mankind, some elements of the visit showed that, at least when the success of the Apollo 11 astronauts were in question, the Yugoslav side leaned to the American one in the space race. The reception of the astronauts, which according the writing of the American side, greatly surpassed the American expectations, testified to this. So did the masses on the streets and decorations the astronauts were awarded, which were a grade higher in rank than those conferred on the Soviet astronauts, as well as the overall attitude the Yugoslav authorities, journalists an public had toward this American success. The political importance of this visit was obvious for both Yugoslav and American sides. The Yugoslav side, which has often balanced between the superpowers, sided openly with that part of the world which wholeheartedly celebrated American success in the conquest of space, and the American one was happy to prove that also in this endeavor it had a communist ally too.

- Price: 6.00 €

Година 1968 – исходиште нове југословенске спољнополитичке оријентације

Година 1968 – исходиште нове југословенске спољнополитичке оријентације

(The Year 1968 – Point of Departure of the New Yugoslav Foreign Policy Orientation)

- Author(s):Ljubodrag D. Dimić

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Diplomatic history, Political history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989), History of Communism

- Page Range:339-375

- No. of Pages:37

- Summary/Abstract:In the world filled with disagreements and quarrels, Yugoslavia was, during the 60s, trying to find its place. Confronted with deep internal crisis its state and party leadership found itself on the important historical crossroad. Experience of the past decades obligated and at the same time, burdened party on power. Dilemmas about the further ways of developing the society were numerous. Growing crisis more and more pressured. Foreign position of Yugoslavia was stabile. Non-alignment politics and one of the leading positions of Yugoslavia in that movement gave the Josip Broz Tito possibility to run the world politics. It was in discrepancy with size, economic potentials and internal stability of the country. Elimination of the external fear indirectly influenced on the development of the internal relations, fights inside the party leadership, „relaxation” of the Yugoslav federation, opening the national question, independency of republics, new constitutional-legal sharpening of the country. Internal crisis was deep, in the same time state and party, ideological and organizational, political and economical, social and moral. Confronted with it, the most responsible Yugoslav politicians from the beginning of 60s noticed that crisis lasted longer that one decade, and that it turbulence in the basis, party on power, occupied state, disarrange institutions and society, threatened international stability of the country. Military intervention of the Warsaw pact in Czechoslovakia in august 1968 changed a lot of things. Declaring a protest against military intervention in Czechoslovakia, Josip Broz Tito basically appealed on the defending of Yugoslavia. Defending the common principles which gained in foreign affairs and interests of socialisms in the world, Tito primary defended uniqueness and positions of his country. Tito was convicted that military intervention in Czechoslovakia directly proceeds from strive to restrain processes in „lager” countries, which Yugoslavia started with its example. Gradually started political „turn” of Yugoslavia towards Europe but in the same time to Moscow was indicated, with series of initiatives and declarations that a wish for better relations existed. In other words, Josip Broz do not won’t to wait changes in politics of the Soviet Union and Europe towards Yugoslavia, he tried to provoke it. He counted that Yugoslavia with its numerous advantages was needed on the East and on the West. Précis definition of Yugoslav foreign position Tito based on the judgment that Europe became a region on which great powers cooperates, despite irreconcilable quarrels in the other parts of the world. That judgment in the same time demanded researching of its own state and national capacities, consolidation of long lasting goals and resolving all internal problems. Tito knew that internal situation in great level create foreign position of the country but he was not ready to accept fact that in Yugoslavia, in that moment, existed crisis and that it had „disturbing character”. Political situation in Yugoslavia he estimated as „good”. He considered that there was no reason for disturbance and internal conflicts. Social and strategic stability on the ”internal level” he judged as sufficient for condemning realistic foreign policy. All aspect showed that existing social discrepancies and confl icts were not passing occurrences but „long lasting components of the social system”. It was political oversight which would seriously threatened stability of the country in next months and years. Visit of the American president Nixon showed that Yugoslavia hold important place on the scale of the foreign priorities of USA. It was certain sign for Tito that USA counts on him, Yugoslavia and non-alignment countries as important factors in attempts to transform the „era of confrontation” in „era of negotiation”. Realization of the visit in the moment of intensifying the conflicts in the Middle East and Vietnam spokes additionally. Nixon’s visit to Zagreb and words that „spirit of Croatia was never ruined and enslaved” were in the same time serious warning that political crisis under the burden of Croatian nationalism which threatened the unity of the country, might in every moment be used. To Tito it was clear that two options existed. European stability was the best guaranty for Yugoslav stability. Crisis which captured Yugoslav federation in the beginning of 70s party leadership tried to solve on few different ways – with new constitutional reforms, strengthening the leaders social role of the CPY, fighting with nationalistic movement in Croatia, strangling the liberal-democratic tendencies in Serbia, „conserving” of the anchoring political conceptions. Structure of the crisis was predominantly political. Identifying the idea of state with the fate of party denied democratic future of the country. The process of economic disintegration left disastrous consequences. Tendencies of the disintegration in the country and party on power injured Yugoslavia on the foreign plan and damaged Tito’s image. Great internal problems absorbed all the important energy of the state and party leadership. It was the main reason of the Yugoslav „passivity” during the first months of the 1971 on the international plan. Tito’s position in the world politics was additionally undermined by undersized accurateness of non-alignment movement.

- Price: 6.00 €

ЈНА на искушењима 60-их година прошлог века

ЈНА на искушењима 60-их година прошлог века

(The Yugoslav People’s Army’s Ordeals in 1960s)

- Author(s):Mile Bjelajac

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Military history, Political history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989), History of Communism

- Page Range:379-417

- No. of Pages:39

- Summary/Abstract:The situation in which the Yugoslav People’s Army (YPA) found itself at the time of the events in Czechoslovakia in 1968 was the consequence of turbulences which had previously been rocking the political leadership, the Communist Party and the Army itself. Life outside of the Army was marked by the economic reform in two phases (1958 and 1965), crisis in the relations between the Yugoslav republics, malfunctioning of political bodies and federal institutions, as was noted on the secret session in March 1962, as well as by Tito’s inconsistency in domestic and foreign policies, further dismantling of the central authority and strengthening of the power of the republics, i.e. of etatism of the republics, all of which affected discussions about the defence concept. The Brioni Plenum in 1966, student demonstrations in 1968, demonstrations and violence of Albanians in Kosovo and Macedonia in 1968, rise of nationalism in Slovenia and Croatia only served to make the situation in which the YPA found itself, more difficult. Within the Army itself, after the one-sided cessation of the US military aid program (1958), the new doctrine was introduced – Strategy of Total People’s War, coupled with the changes in formation, that would continuously be upgraded. Although the new doctrine foresaw the combination of frontal and guerrilla warfare, the conflicts insured as to its details. There was a pressure that as much rights and duties in the defence system be allotted to the republics. A group of generals demanded that „self-management” be also introduced in the YPA. Tito, who was the supreme authority in Army matters, didn’t want to give up the unity and to allow anyone to interfere with his leadership. Because of that he had confl icts with the highest Party and political leaders. However, he too was inconsequential when it came to the highest cadres. Because of his resistance to deposition of Ranković, Tito dropped Gošnjak and replaced him with a new minister (1967). All that was coupled with smaller or larger purges of the generals’ corps (only in 1968, 38 generals and 2.400 officers were relieved of their posts). Tito was also the initiator of the new rapprochement and full cooperation with the USSR and the Warsaw Pact (natural hinterland). All modern and heavy weapons started to be obtained from that side, from 1961 onwards. The assessment of the Berlin and Cuban crisis, and particularly the crisis in the Mediterranean and the war in the Middle-East in 1967 certainly contributed to such approach. The Soviets and the Yugoslavs found themselves on the same side then, supporting Arab nations. Tito judged that the main potential threat to Yugoslavia was – the West. During 1960s it became obvious that the YPA, its partisan elite, started to be eroded by nationalism. This caused anxiety with the pro-Yugoslav cadre. This conflict would remain a staple characteristic of this army until its demise in 1992. The consequences of the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact were manifold for the YPA, but also for the country as a whole. Strictly militarily and strategically, all further assessments would recon with the possibility of attack from any side, and war-plans and other measures would be adjusted accordingly. Technical modernization of the Army and further development of the military- -industrial complex gained priority. Having analyzed shortcomings of mobilization activities, comprehensive measures were undertaken in order to improve the situation. The Air-Force and Anti-Aircraft Defence, apart from strengthening capacities for defence from the ground, realized a system of underground airfields and shelters must be adopted, as well as putting the whole territory under radar control. After the political critique of the Army in autumn 1968, it was speedily decided that Central Committees of the republics take defence affairs into their own hands, that general-staffs in the republics be activated, that military staffs were to be founded in municipalities, as well as units and battalions armed with light modern weapons, to secure the communication system and to determine precisely the role of radio and smaller radio stations in case of war. It was believed, with all these measures, the technocratic organization of the Army could be overcome. A new Bill on National Defence was railroaded through the Parliament. Thisopened permanently the question of sovereign command competence and use of the armed forces in Yugoslavia. During the constitutional changes (1969-1974) the wish of some republics was perceptible to gain as much rights in the defence sphere and in managing of the Territorial Defence. The assessment of the student demonstrations in 1968 wasn’t unanimous within the then military top brass. To be precise, it was radically diverging. The question if a socialist army may intervene in internal political situation was raised then. Tito wanted the Army to concentrate on watching the borders and not doing anything without his explicit approval. However, the events in Kosovo and Macedonia (1968) with demonstrations and elements of rebellion of the Albanians, as well as the escalation of the „Mass Movement” in Croatia, soon convinced also the professed „liberals” among generals that the Army must react in certain situations when public order and the unity of the country are endangered.

- Price: 6.00 €

Pripremanje terena: odjek globalnog studentskog bunta 1968. godine u jugoslavenskom omladinskom i studentskom tisku

Pripremanje terena: odjek globalnog studentskog bunta

1968. godine u jugoslavenskom omladinskom i studentskom tisku

(Setting the Stage: The Echo of the Global Student Revolt of 1968 in Yugoslav Youth and Student Press)

- Author(s):Marko Zabak

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Political history, Social history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989)

- Page Range:419-452

- No. of Pages:34

- Summary/Abstract:Yugoslav youth press, the scope of various journals and newspapers published by a network of official youth and student organizations, played a vital role in the late 1960s in communist Yugoslavia. This essay focuses on just one of its aspects: a surprisingly loud echo of the global student unrests that could betraced within these journals. The essays examines the most signifi cant examples of the youth press journals of the three central Yugoslav republics Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia, namely, Belgrade’s Student and Susret, Zagreb’s Polet, Omladinski tjednik and Studentski list and Ljubljana’s Tribuna and Mladina. Using the example of several central themes that mostly „preoccupied” the aforementioned journals, the essay examines the argumentation used, the adjoined graphical support, the most relevant authors and frequent controversies which could be found in the writings of the youth press about these stormy youth and similar „progressive” movements happening worldwide. More specifically, the essay closely portrays writings of the youth press journals about the student activities in Germany, France and Italy, about the Polish March student demonstrations and the Prague Spring, about the various protests directed against the war in Vietnam as well as about the USA-based hippie and black movements for civil liberties and finally, about the solidarity actions of the Yugoslav students with respect to the mentioned processes. Treated as a separate journalistic genre with specific characteristics that evolved within the institutional framework of the ruling communist party, the examined journals of the Yugoslav youth press, despite some mutual differences, demonstrate interesting common trends. Most of the investigated journals show an extraordinary strong interest and predominantly positive and supportive attitude towards these revolutionary movements occurring on a global scale, which was not always in accordance with the writings of the mainstream press and often hesitant attitude of the official regime. In this sense, this essay also provides a firm basis for any future comparison between the treatment of the global student turmoil by the youth press and the important role that these youth journals played during the 1968 June student unrest in Yugoslavia, which in itself is left outside the scope of this essay.

- Price: 6.00 €

1968” u Jugoslaviji – Studentski protesti između Istoka i Zapada

1968” u Jugoslaviji – Studentski protesti između Istoka i Zapada

(„1968” in Yugoslavia – Student revolt between East and West)

- Author(s):Boris Kanzleiter, Krunoslav Stojaković

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Cultural history, Political history, Social history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989)

- Page Range:453-480

- No. of Pages:28

- Summary/Abstract:The student protests of June 1968 in Yugoslavia were a shock for the political elite. It concerned the first open mass protests after the consolidation of power by the communist party after the Second World War. The gap between the requirement of the federation of the communists to create a democratic and fair society and the disappointing social and political reality became clear. The student protests marked the end of the illusion of a harmonious „conflict-free society”. The student protests can be understood only in the context of the criticism at the reality of Yugoslav socialism, which was articulated already since beginning of the 60’s by intellectual ones from the surrounding the journal Praxis in addition, writers and film producers from the avant-garde art and culture scene. The characteristic „of the Yugoslav 1968” in the global connection exists in the integration of elements of the contemporary youth protests in east and west.

- Price: 6.00 €

Студентске демонстрације у Београду 1968. године

Студентске демонстрације у Београду 1968. године

(Student Demonstrations in Belgrade in 1968)

- Author(s):Momčilo Mitrović

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Political history, Social history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989)

- Page Range:481-491

- No. of Pages:11

- Summary/Abstract:The paper gives an extended chronology of the student demonstrations in Belgrade in 1968. Presented are the main programmatic documents, demands and key events of the demonstrations in the Students’ Town and at faculties. Held within a global context, the demonstrations drew attention for the first time since WW II to deviations of self-managing socialism in Yugoslavia, as well as disaffection with the Party and bureaucratic establishment. Without challenging the role of the Union of the Communists of Yugoslavia, the student remained loyal to the one-party system, believing in the possibility of rectifying „mistakes” and in Communists setting the example of honesty. Despite some incompleteness of the system critique, the demonstrations of 1968 in Belgrade, were, due to their earnestness, an unprecedented phenomenon which seriously, albeit briefly, shook the political and the state establishment of the country.

- Price: 6.00 €

Материјални положај београдских студената и студентске демонстрације 1968. године

Материјални положај београдских студената и студентске демонстрације 1968. године

(The Material Situation of the Belgrade Students and the Student Demonstrations in 1968)

- Author(s):Dragomir Bondžić

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Cultural history, Economic history, Political history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989)

- Page Range:495-517

- No. of Pages:25

- Summary/Abstract:Among the students’ demands during the June demonstrations of 1968, material problems of students and the University and demands that they be solved as soon as possible, also featured on the students’ list of demands, albeit on modest scale and at the end of the list. Much more than by students themselves, this motive were used by the government and the press, in order to compromise them and reduce their protest to defense of selfish sectional interests. Throughout the years, the living and working conditions of the students in Belgrade were so bad that they left perceptible marks on social structure, efficiency of studying, and certainly influenced, together with other factors, the swelling of rebellious feelings, irritation and tensions among the students. Therefore they shouldn’t be left out when looking for the causes of the June demonstrations of 1968. The material problems and problems of everyday life of the Belgrade students were numerous, deep and difficult to solve under the conditions prevailing during the economic reform and attempts at introducing more efficient market parameters in Yugoslavia’s socialist economy in mid-1960s. Despite efforts and investments since 1945, these problems persisted and increased over time. They affected lodging and solutions of lodging problems, food and its improvement, credits and grants for students, health-care, and operation of the Students’ Community as well as matters of medication, refreshment, cultural and sport life of the Belgrade students. These problems were held up already before the student demonstrations, and the demands of the students’ protest of June 1968 gave a new impulse to attempts at improving the students’ living standards. However, although the authorities speeded up passing of some decisions aimed at improving the students’ living standard which had already been in the making, the more serious and more.

- Price: 6.00 €

Unutrašnjopolitičke i vanjskopolitičke aktivnosti Jugoslavije nakon intervencije Varšavskog pakta u Čehoslovačkoj 1968. godine

Unutrašnjopolitičke i vanjskopolitičke aktivnosti Jugoslavije nakon intervencije Varšavskog pakta u Čehoslovačkoj 1968. godine

(Yugoslavia’s Activities in Domestic and Foreign Policy after

the Intervention of the Warsaw Pact in Czecholsovakia in 1968)

- Author(s):Hrvoje Klasić

- Language:Croatian

- Subject(s):Diplomatic history, Military history, Political history, Social history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989)

- Page Range:519-547

- No. of Pages:29

- Summary/Abstract:Five countries of the Warsaw Pact committed the act of military aggression on Czechoslovakia in late August 1968. That was the culmination of pressure on the Czechoslovak political leadership aimed at putting an end to political, economic and social changes in that country. Tito’s Yugoslavia was a country which followed the developments in Czechoslovakia with particular interest. From the very beginning, the reaction of the Yugoslav political, but also general public was unanimous, and it boiled down to condemnation of the intervention and support for the Czechoslovak people and leadership. Parallel with the reactions to the situation in Czechoslovakia, a theory was launched, prophesizing the continuation of the military intervention precisely in Yugoslavia. In order to successfully defend the country, the Yugoslav political leaders started a number of activities in domestic and foreign policy. The activities in the internal policy comprised mobilization of the society on the one hand, and defensive military preparations on the other. The latter caused difficulties, not only due to the preponderance of the aggressor, but also due to the necessary changes in the existing defence system. In the field of foreign policy Yugoslavia strove to utilize the position she had been building up on the international scene for years. As one of the leaders of the Non-Aligned Movement, Yugoslavia also used Czechoslovakia’s example to stress the need for peaceful resolution of problems in the world. Furthermore, ever since the split with Stalin, Yugoslavia normalized her political and economic relations with the West. By keeping and even strengthening these relations in the new situation, the capitalist West stepped to the fore as one of the most important factors of the socialist Yugoslavia’s stability. The Yugoslav society of the second half of 1960s faced a number of problems, particularly of internal economic and political character. In the course of 1968 the dissatisfaction with the situation culminated in the students’ revolt and strike. The possibility of the country being endangered also from without at such a moment, poised an additional problem. However, despite fears and prognosis, the possibility of an attack from the East and the atmosphere created in connection with that, caused a reverse effect. The respect for the Party was renewed, the society was homogenized once again, and Yugoslavia’s reputation in the world was strengthened. The spoiled relations with the countries of the Warsaw Pact, particularly with the USSR, were not of long duration. Instead of a military intervention, the relations were completely normalized already next year. This normalization was hailed in Yugoslav, but also in the world public, as another victory over the „Big Communist Brother”.

- Price: 6.00 €

Економска емиграција из Југославије шездесетих година XX века

Економска емиграција из Југославије шездесетих година XX века

(The Economic Emigration from Yugoslavia in 1960s)

- Author(s):Slobodan Selinić

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Economic history, Political history, Social history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989)

- Page Range:549-574

- No. of Pages:25

- Summary/Abstract:The economic emigration was one of the most striking features of Yugoslavia’s development in 1960s. It was caused by the economic development of Western countries which felt the need for labor force from Eastern Europe, economic crisis at home, undeveloped labor migrations within the country, excess labor force, particularly prior to the economic reform of 1965, larger traveling opportunities, propaganda of those who had already left etc. There was some half a million Yugoslav workers in Western Europe by the end of 1960s, and together with those overseas, the total was some 600-700.000. In the West- European countries, the largest number of emigrants lived in FR of Germany (300.000), France and Austria. Particularly in the first half of 1960s a large number of emigrants were leaving illegally or without the authorities’ permission or knowledge. In the second half of the decade, the Yugoslav government strove to put this process under control through a number of treaties with Western countries concerning employment of workers from Yugoslavia (with France in 1965, with Austria in 1965, with Sweden in 1967, with Germany in 1968). Just how important migration to work abroad was is shown by the fact that Yugoslavia received large foreign-currency sums in that way and that they increased each year. (There is an information that Yugoslav workers abroad sent 120 million dollars to the country in 1967).

- Price: 6.00 €

Југославија, Ватикан и случај Драгановић 1967–1968. године

Југославија, Ватикан и случај Драгановић 1967–1968. године

(The Yugoslavia, Vatican and the Draganović Case 1967–1968)

- Author(s):Radmila Radić

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Diplomatic history, Political history, Social history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989)

- Page Range:575-611

- No. of Pages:37

- Summary/Abstract:The improvement of the relations between the Vatican and Yugoslavia during the second half of 1950s and the first half of 1960s resulted in a number of concessions from both parties. One of the demands Yugoslavia kept reiterating from the very beginning was that the Vatican stop lending support to the clerical emigration hostile to Yugoslavia and to remove rev. Krunoslav Draganović from St. Bartholomew College in Rome. At the demand of the Yugoslav bishops to depoliticize the College, the Vatican removed Dr. Krunoslav Draganović from it in late 1958. This opened the door for further improvement of the relations. Appointment of Dr. Đura Kokša as the rector of the College, was seen as another concession to Yugoslavia. Thanks to the change of Vatican’s policy toward contacts with the communist authorities behind the „Iron Curtain” since Pope John XXIII and thanks to drafting a new eastern policy (Ostpolitk) of the Holy See, whose main proponent was cardinal Casaroli, conditions for improvement of relations with Yugoslavia were also created. Pope Paul VI tried to carry on the policy of his predecessor and to establish a kind of dialogue with communist regimes with the aim of improving the situation of Roman-Catholic faithful in Eastern Europe. When the negotiations for conclusion of the Protocol between Yugoslavia and the Holy See started, one of the points the Yugoslav party particularly insisted on was the end to anti-Yugoslav propaganda and complete depolitization of St. Bartholomew’s College. It was also insisted that the Vatican cease to support the Ustasha emigrants. The Vatican was willing to subordinate the problem of émigré priests to higher ecclesiastical and political interests. Within the framework of rapprochement the problem of Draganović was also solved. He crossed the Yugoslav-Italian border near Trieste on September 10, 1967, and it remained unclear for a long time if he did it on his own free will or was he abducted. In agreement with the Holy See he was not indicted and he spent the rest of his life peacefully in Sarajevo. Several years after his return the whole case was hushed up in Yugoslav press and public. However, the problem of hostile activities of emigrants against Yugoslavia abroad wasn’t solved with this case.

- Price: 6.00 €

1968. и либерализација југословенског позоришта: БИТЕФ и „Коса”

1968. и либерализација југословенског позоришта: БИТЕФ и „Коса”

(1968 and the Liberalization of Yugoslav Theater: the BITEF and „Hair”)

- Author(s):Anja Suša

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Theatre, Dance, Performing Arts, Cultural history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989)

- Page Range:613-631

- No. of Pages:19

- Summary/Abstract:1960s brought about liberalization in all spheres of life. Thanks to her specific policy, Yugoslavia was in a special position, constantly balancing between consumerist influences of the West and the communist ideology. The achievements of counter-culture left their marks on all arts, and thus on theatrical art too. The dominant concept of the „box stage” and the theater based on a drama text, on which theatrical art of the Western civilization was founded was abandoned in this period. Instead of that, theater became the place of political activity and direct clash with the reality. Theater left the indoors-space and went into the street, provoking and searching through direct contact with the audience, expanding the limits of its activity. Theatrical artists of those days found inspiration in distant cultures and civilizations, applying in their plays achievements of catacaly or of No drama. The theater of this period was more active politically and socially than ever in its history, facing the reality rather than running away from it. The most important theatrical influences during 1960s came to Yugoslavia from America, which had the same inspirational role for theatrical rebels of 1968 as Germany had for ideologues of 1968. 1960s brought certain liberalization in Yugoslav theater too, which was quite in keeping with the trend of „opening” in other spheres of the society. One of the watersheds in the history of Yugoslav theater was 1967 because for the first time Belgrade became equal part of the world theater system in the full sense of the word, thanks to the founding of the BITEF (Belgrade International Theater Festival). That year the Belgrade theater audience could for the fi rst time see some of the newest world avantgarde theatrical trends. It was no coincidence that the idea to start the festival came from the Atelje 212, the most avant-garde theater in Belgrade in those times. Having made a bang like a bomb, during the next few years the BITEF became a reference point for many young Yugoslav authors. However, despite diffi culties and occasional misunderstanding of conservative part of the theatrical community, the BITEF greatly infl uenced the formation of taste of young artists, above all of those who by the year when they were born, belonged to the so-called „generation of 1968”. It is very interesting to note that theatrical professionals within official institutions showed „decent” interest in avant-garde theatrical trends and that considerable space in the leading cultural journals was devoted to critical essays about certain phenomena coming, above all, from the West. The theatrical „case” of staging the cult play Hair, shows the openness of the Yugoslav society, particularly in cultural matters. By allowing Hair to be played, the regime made possible the incursion of the latest theatrical trends into Belgrade theater, but at the same time, it institutionalized and toned down the „spirit of rebellion”.

- Price: 6.00 €

„Buntovna” 68. i još neke godine u Istri

„Buntovna” 68. i još neke godine u Istri

(The „Rebellious” 1968 and Some Other Years in Istria)

- Author(s):Darko Dukovski

- Language:Croatian

- Subject(s):Fine Arts / Performing Arts, Cultural history, Social history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989)

- Page Range:633-654

- No. of Pages:22

- Summary/Abstract:The crisis of the „socialist” society was made „known” to the Yugoslav public through the student protest and vociferous critique by young intellectuals, mostly of „leftist” leanings (although those with „right wing” inclinations also took part in the „movement”). Publicly displayed dissatisfaction and revolt of the students were the first overt critique of the „self-managing socialism” as seen by the Party, i.e. its leaders. With their acts and demands, the students asked the State to prove its legitimacy, pitching themselves against it and bringing its officials (the „red bourgeoisie”) to book. The most „revolutionary” consequence of 1968 was demystification of the government and the system. According to the demands the students voiced, it was the continuation of the „revolution” or at least the „return to the original revolutionary principles”. The „revolutionary students” declared the Zagreb University the „Socialist University of the Seven Secretaries of the SKOJ”, and the Belgrade University the „Red University Karl Marx”, which itself tells enough about their goals „(…) or it was just a gag or a cheap trick”. Zagreb experienced no riots or a strike but a week’s turbulences left their mark. Particularly on those who were kicked out of the University and who lived for years on illusions that they had been „revolutionary students”. That spirit of the 1968-rebellion, of change, liveliness, of dispersing boredom and of possibility of choice was felt in Istria solely through the struggle for freedom of cultural activity and unconventional works of groups of young cultural activists and artists. Nothing particularly important happened in Istria in 1968 that could be explained as a consequence of students’ unrest, of radical left-wing leanings, anarcho-liberalism, etc, except for participation in the unrests of few students from Istria, some of whom were pardoned and some not. The turbulences which were ideologically closest to students’ demands for free speech and other „civic” liberties, played out in the field of culture, i.e. among the cultural activists. The main question was what kind of culture was needed and who needed it unencumbered with daily politics and dictated by Party committees. During the belated aftermath of the „anarcho-liberal” ideas a group of young cultural activists was founded in Pula in 1970, independent of the Communist Party, the Martica hrvatska or the Čakavski sabor , who saw their contribution to culture and arts in relentless critique of the society and on the level of European cultural achievements and the ideas of the „New Left”. The most important event was the founding of an informal group of young enthusiasts, cultural workers, who would actively participate in forming politicsfree culture of the city: the Author Group Pol 5. Their cultural actions were, apart from publishing the journal Trefi lo, organizing photo exhibitions-cum-poetry reading evenings, showing of amateur films etc. For these purposes they made contacts with the Youth Literary Club Istrian Combatant and the Experimental Youth Scene. Members of these organizations had dual membership in both organizations. These very open-minded societies which readily accepted every gifted young individual. Some individuals were active in youth associations such as the Author Group Pol 5, the Experimental Youth Scene and the Literary Club Istrian Combatant, taking part in social cultural activities, but had no ambitions to create movements. Their interest in social and political processes remained in the realm of theorizing and cultural essays.

- Price: 6.00 €

Хронологија важнијих догађаја 1968. године

Хронологија важнијих догађаја 1968. године

(Chronology of the Important Events in 1968)

- Author(s):Nataša Milićević

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Cultural history, Diplomatic history, Economic history, Political history, Social history, Post-War period (1950 - 1989)

- Page Range:657-678

- No. of Pages:22

- Summary/Abstract:Chronology of the Important Events in 1968

- Price: 5.00 €

Библиографија изабраних радова о 1968. години

Библиографија изабраних радова о 1968. години

(Selected Bibliography on 1968)

- Author(s):Dragomir Bondžić, Slobodan Selinić

- Language:Serbian

- Subject(s):Bibliography, Post-War period (1950 - 1989)

- Page Range:679-696

- No. of Pages:18

- Summary/Abstract:Selected Bibliography on 1968

- Price: 4.50 €