Primordia Romana. Mityczna przeszłość Rzymu i pamięć o niej w rzymskich numizmatach zaklęta.

Author(s): Agata A. Kluczek / Language(s): Polish

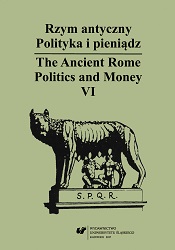

The focus of this study is the mythical-ideological content of iconography introduced on Roman coinage, giving us an idea about the ancients’ perception and understanding of the past. This past is a construct emerging from the founding myths, or stories about heroes from Rome’s beginnings set in the early, legendary phase of its past. Among them was Aeneas — the forefather, who was a reminder of Troy, and Romulus and Remus, the sons of Mars and founders of the city (conditores Urbis), whose childhood fate heralded a great future of Rome and whose deeds led to the birth of the City (Urbs).The past evoked by monetary representations of these characters is reconstructed, the origins and early history of the Romans are explained. In coins, whose content draws on that past, one can see monuments to Rome’s ancient history: memoria rerum Romanarum. Allusions to the earliest beginnings stemmed from the expectations and goals of the issuers of coins. Elements of the Roman myth were brought back from tradition to create an image of gentes or individuals by metaphorically erecting their monuments. In this way, a strong bond was forged between the mythical past conveyed in myths and the issuer’s contemporary times. The past captured on coins changed according to the expectations and goals of their issuers, while coins were primarily „monuments in miniature” to polititians and emperors and were their way of showing recognition for Rome’s tradition and past.Starting from the 3rd century BCE and continuing to as late as the 4th century CE, on Roman coinage there appeared imagery invoking Rome’s origins and early beginnings. Hidden in this imagery was the knowledge about select episodes from the founding tradition possessed by the Romans of that time.More importantly however, these monetary depictions prove the attractiveness and significance of particular mythical themes. At the same time, the contents on coinage provide exceptional examples of the updating and politicizing of the Roman myth. It was manipulated by means of confining it to certain themes while abandoning others. Modifying the themes drawn from myths was to a certain extent determined by the limitations imposed by the numismatic vehicle itself, where there was no room for lengthy inscriptions or elaborate iconography. As a result, only simplified, symbolic versions of stories about Rome’s beginnings were depicted on coinage. They primarily involved images of divine, human, and animal heroes: Mars and Rhea Silvia, Aeneas, Romulus, a she-wolf, etc.Interestingly, however, the message concerning Rome’s origins and early history has not lost any of its vividness over the centuries. These images were presumably not seen as solely mythical episodes but served their issuers’ current goals and interests. Their evolving consisted in a gradual deepening of the significance of singular iconographic themes as they were linked with universal values. These values were either expressed directly in inscriptions accompanying depictions or emerged from the images of the mythical heroes preserved by tradition and transposed into the needs of state ideology. Herein lies the uniqueness of the imagery referring to Rome’s earliest beginnings and most ancient history, as well as the attractiveness of this material for study.The first part of this book discerns the themes featured on coinage of the founding myth from Aeneas to the royal epoch. Rather than reconstructing mythical stories or, based on them, delivering a conceivably consistent and logical lecture, the author attempts to explain the sense of images featured on coins and medallions through references to the literary tradition. This part points out the similarities, originality, or uniqueness of solutions applied to coinage in relation to a broader iconographic tradition. Each successive chapter is devoted to the following heroes: Aeneas, the parents of the founders — Mars and Rhea Silvia, next the she-wolf, Remus and Romulus, and the heroes from royal times — anonymous Sabines, Tarpeia, and Roman kings. The myth reflected on Roman coinage boils down to these characters who — represented in the iconography of coins and medallions — evoke associations with events from the origins and earliest history of Rome.Part two orders the source materials chronologically from the Republic to the years of the Constantine dynasty rule. Succesive chapters address who, when, why, and what particular mythical themes were chosen for their issues. During the Roman Republic, attention was drawn to familial issues, where the Trojan myth was one of the many possible themes articulating the noble background of a gens. The high status of the Julii, especially Gaius Julius Caesar (C. Iulius Caesar), then Augustus, and generally the Julio-Claudian dynasts changed this state of affairs: the private Trojan myth advanced to the status of a state myth. The coin imagery reflected this proces to a certain extent, in it, primarily connecting the themes of Aeneas and Romulus with depictions of the Temple of Divus Augustus. Subsequently, rulers mainly used the theme of Rome’s she-wolf. It was used on a large scale especially in the reign of the Flavian dynasty (69—96) and Maxentius (306—312), but also by other emperors, who sought ideological support for their reign and thus demonstrated their attachment to tradition.This part also shows the reappearance of various mythical themes in the context of anniversaries in the reign of the Antonine dynasty and the “Crisis of the Third Century”. Celebrating the foundation of the City (dies Natalis Urbis) during Hadrian’s rule (117—138) and its subsequent anniversaries, the 900th anniversary in the reign of Antoninus Pius (138—161), and the millennium in the reign of Philip the Arab (244—249) was a favorable occasion for remembering Rome’s beginnings in monetary propaganda.The focus of part three is imperial virtues, virtutes, which were illustrated by three principal iconographic themes, bringing forth the heroes of Rome’s founding myth. They are: Aeneas, mostly depicted as the one who carries out the father and leads out the son, saving them from the danger of death (Pius Aeneas); the she-wolf who takes Romulus and Remus under her care, nurtures and rescues them (Lupa Romana); Romulus depicted as a warrior and a triumpher in one (Romulus tropaeophorus). These three iconographic themes, featured in numerous variants, served as representations of the three values. They are the following: pietas, aeternitas, and virtus. The extent to which the images of Aeneas, the Roman she-wolf, and Romulus were presented in this sense shows their emblematic character. It also proves an immanent connection between the sense of such depictions and primary values in the Roman state, important for the continuity of the empire.Part four begins with references to the origins and earliest history of Rome and their representations on medallions, that is occasional issues, and to a special group of imperial coins bearing replicas of images previously used by other issuers, called imitation and restitution coins (nummi restituti). They offered an exceptional opportunity to comment on the rulers’ approach to the mythical past. In part four, there is also room to discuss the character and scale of images concerning the myth of Rome’s foundation in depictions on provincial coins and the contorniate. Next, the book provides a synthesis of the studied imagery. The numismatic representations have been discussed in terms of their themes and originality. The words inscribed on coins have been analyzed along with the significance of inscriptions as commentary to images.Finally, in the concluding chapter, the determinants and regularities in the selection of themes from the Roman myth have been indicated. Firstly, it has been noted that favorable conditions were created by the then current situation in the empire, emperor’ s personality, and issuer’s own interest, the latter being the interests of gentes during the Republic and those of rulers — the strenghtening of their power — during the empire. Secondly, it has been emphasized that the choice of mythical themes was not random. They were not commonly used, but were always part of political agenda of the issuers.Focusing on the three leading themes: Aneneas, Lupa Romana, and Romulus tropaeophorus, one can discern three periods of their appearance on Roman coinage. The first comprises, generally speaking, the 1st BCE and the second half of the 1st CE. The popularity of the Aeneas theme in that period is well-documented and unprecedented before or after. All the three themes coexist on the coinage from the years c. 120—160. At that time, not only political circumstances and emperors’ tastes determined the choice of those themes, but, as can be inferred from other contemporaneous artifacts, they were also part of certain artistic-ideological convention. The beginning of the next period is marked by Rome’s millennium and its end in the middle of the 4th century. An extremely popular image during the first half of this long period of time was that of a warrior striding with a tropaeum on his arm, while the theme of Lupa Romana, characteristic for this late period, remained a long-lasting preferance.

More...