Author(s): Kutay Onayli / Language(s): English

Publication Year: 0

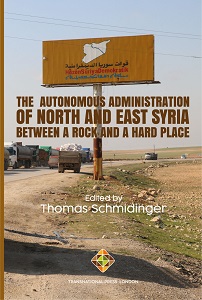

The Greek community of Istanbul found itself between a rock and a hard place in the Autumn of 1922. With the Hellenic military expedition in Asia Minor ending in riotous defeat and the Allied occupation of the Ottoman capital soon to come to a close, the city’s 100,000 or so Hellenes feared coming Turkish reprisals. Weary of a decade of Turkish-nationalist Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) government, which had repeatedly attacked the Constantinopolitan Greek community’s communal rights and autonomy and had in effect besieged its religious, educational, cultural, and economic institutions, the city’s Greeks had offered Istanbul’s Allied occupiers a warm welcome. The community – or at least its political leadership, press, and numerous philantrophic and cultural institutions – had also been outspoken in its support of the Greek war effort in Anatolia. Just when, however, centuries of what was effectively second-class subjecthood as tolerated but often vilified non-Muslim Ottoman dhimmi seemed to be coming to an end, Mustafa Kemal’s new Turkish nationalist movement in Ankara gained the upper hand, and would soon come to rule all of Turkey. Aware that Greek communities across Asia Minor were being displaced along with the retreating Hellenic army and fearing a repeat of the Great Fire of Smyrna, which, accompanied by massacres of non-Muslim civilians, had eradicated Greek life in the fabled Aegean port city, the community found itself at its most fragile in the final days of the Ottoman Empire. A rapid exodus to Athens began, especially amongst those who had had been politically active during and after the Great War, and by the time the Ankara government took over Istanbul from the Allies, the city’s Greek population was beset by nothing less than total uncertainty, and had essentially lost its communal leadership and political elite. Though this has received little scholarly attention, the community also lost much of its cultural leadership in this period, with a majority of the city’s leading intellectuals in forced exile in Greece by 1923. To give a sense of the intellectual vibrancy and diversity that Greek Istanbul held – and lost – in the early 20th century, the departees included elder statesmen of Greek Ottoman letters such as Manuel Gedeon (a great historian of the Greek Orthodox Church and Ottoman Greeks more generally) and Stavros Voutyras (who had been running various iterations of his newspaper Neologos for nearly 50 years) to a younger generation of intellectuals such the Spanoudis (Konstantinos the firebrand publisher of the city’s leading newspaper Proodos, his spouse Sofia a Dresden-trained pianist and music critic) and the Delis (Ipatia a translator who was published work by Oscar Wilde amongst others in late Ottoman Istanbul, her husband Christos the poet behind Ano-Kato, perhaps the most successful of the city’s nearly two dozen Greek-language political satire magazines after 1908). The city’s fabled Greek Philological Society – the fountainhead of all kinds of intellectual and social debate from literary criticism of Ancient Greek classics to essay competitions on the nature of love and the marriage in the 1910s – was shuttered, its singular library shipped off to Ankara never to be seen again. Its grandiose neoclassical headquarters, in an ironic twist that very much foreshadowed the difficult decades awaiting the city’s Greeks, would be confiscated and turned into the headquarters of Kemal Atatürk’s ruling Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, CHP).

More...