We kindly inform you that, as long as the subject affiliation of our 300.000+ articles is in progress, you might get unsufficient or no results on your third level or second level search. In this case, please broaden your search criteria.

The publication is devoted to the role played by the means of technical reproduction and the image transmission processes in promoting avant-garde concepts of art in the early decades of the twentieth century. Referring to Walter Benjamin’s thesis from the 1930s that photography and the availability of reproduction changed the modern concept of art by offering new artistic tools, the author seeks to explore how the use of reproduction influenced the new ways of art presentation and the development of an international network of artistic exchange.

More...

The book contains texts of well-known historians, museologists and archivists of Łódź, who aimed at presenting the impact of the Polish-Soviet War (1919–1921) on the functioning of Łódź and its inhabitants as well as the participation of Łódź residents in this armed conflict. The authors present the role of the city as an administrative center and a center of socio-political, cultural and military life. They picture the activities of the Łódź community as well as the local political, intellectual and economic elites, confronted with the war with Bolshevik Russia. The authors draw expressive portraits of the Łódź politicians and social activists. At the same time, they are looking for traces of this dramatic period in the modern image of the city, its museums, archives and at the great necropolises of Łódź. They ask questions about the place of 1920 in the collective memory of generations of Łódź residents.

More...

The Historical Chronology of Hungarians in (Czecho)Slovakia in the Period of 1914–1945 is a result of many years, or rather, many decades of research work by the author, Gyula Popély. It also fits well into the portfolio of the Forum Minority Research Institute, as it complements and forms a unified whole with the chronology by Árpád Popély, published by the institute in 2006, which processed the history of Hungarians in Czechoslovakia between 1944 and 1992. The present volume brings closer to the reader the first two periods of the history of Hungarians in Slovakia in the form of factual descriptions in chronological order: the history of the years between 1914 and 1938, and between 1938 and 1945. The volume has been divided by the author into five structural parts. The descriptions of the first thematic and temporal unit show the path of Hungarians leading to the position of a national minority, starting from the outbreak of the First World War to the signing of the Treaty of Trianon. This section deals with, among others, the formation and establishment of the Czechoslovak statehood, the peace conference, the period of the Soviet Republic of Hungary, and the conclusion of the Trianon peace. The second chapter of the volume is entitled The Hungarian Multiparty System in Czechoslovakia (1920–1936). Measured in time, this is the book’s most voluminous and least dramatic part. It shows how the Hungarians fit into the Czechoslovak state and how they fought their political struggle with the Czechoslovak state power. The third structural part is entitled Under the Flag of the United Provincial Christian Socialist Party and Hungarian National Party (1936–1938) and covers the events of the period from the formation of the United Hungarian Party to the first Vienna Award, assigned to specific dates. It is a chronicle of a serious time of crisis, at the end of which the majority of Hungarians in Slovakia became citizens of Hungary again as a result of the first Vienna Award. The fourth chapter only covers the events of just over 6 months, in essence, the period of Slovak autonomy. This and the next chapter—which is a coverage of the period from March 1939 to the spring of 1945—present in parallel the life of Hungarians left in Slovakia and those who, as a result of the First Vienna Award, became nationals of Hungary. It is a chronicle of a tragic era when events such as the devastation by World War II and the tragedy of the Holocaust frame the story.The volume is closed with a personal name and place name index.

More...

This volume is comprising biographies of Fridtjof Nansen, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, Aristide Briand, Walther Rathenau, Giuseppe Motta, Eleftherios Venizelos, Lloyd George, Benito Mussolini and Josef Stalin. // Emil Ludwig (originally named Emil Cohn) was born in Breslau, now part of Poland. Born into a Jewish family, he was raised as a non-Jew but was not baptized. “Many persons have become Jews since Hitler," he said. "I have been a Jew since the murder of Walther Rathenau [in 1922], from which date I have emphasized that I am a Jew.“ Ludwig studied law but chose writing as a career. At first he wrote plays and novellas, also working as a journalist. In 1906, he moved to Switzerland, but, during World War I, he worked as a foreign correspondent for the Berliner Tageblatt in Vienna and Istanbul. He became a Swiss citizen in 1932, later emigrating to the United States in 1940. // During the 1920s, he achieved international fame for his popular biographies which combined historical fact and fiction with psychological analysis. After his biography of Goethe was published in 1920, he wrote several similar biographies, including one about Bismarck (1922–24) and another about Jesus (1928). As Ludwig's biographies were popular outside of Germany and were widely translated, he was one of the fortunate émigrés who had an income while living in the United States. His writings were considered particularly dangerous by Goebbels, who mentioned him in his journal. (Wikipedia)

More...

Edited and initiated by Nicolae Iorga // Bucharest, 1938, published by »Monitorul Oficial« and »Imprimerile statului« during Calinescu’s mandate as Prime Minister. // Armand Călinescu (4 June 1893 – 21 September 1939) was a Romanian economist and politician, who served as 39th Prime Minister from March 1939 until his assassination six months later. He was a staunch opponent of the fascist Iron Guard and may have been the real power behind the throne during the dictatorship of King Carol II. He survived several assassination attempts but was finally killed by members of the Iron Guard with German assistance. (source: WIKIPEDIA)

More...

Edited and initiated by Nicolae Iorga // Bucharest, 1938, published by »Monitorul Oficial« and »Imprimerile statului« during Calinescu’s mandate as Prime Minister. // Armand Călinescu (4 June 1893 – 21 September 1939) was a Romanian economist and politician, who served as 39th Prime Minister from March 1939 until his assassination six months later. He was a staunch opponent of the fascist Iron Guard and may have been the real power behind the throne during the dictatorship of King Carol II. He survived several assassination attempts but was finally killed by members of the Iron Guard with German assistance. (source: WIKIPEDIA)

More...

Published in 1995 by EDITURA FUNDAȚIEI CULTURALE ROMÂNE, BUCUREȘTI

More...

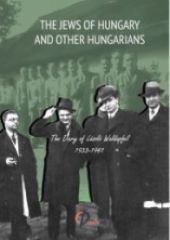

This diary was not meant to be presented originally to the wider public. Its author is a young man of Hungarian-Jewish background, who is writing about the events in his life and the world around him in the 1930s and early 1940s. Did he ever imagine that he was writing a veritable historical chronicle, reflecting on the complexities of his identity in the light of the gradual normalization of discriminatory politics and slide toward genocide? We shall never be able to find this out, because soon after the last diary entry, he is called up to forced labor service on the Russian front from where he would never return.

More...

The book presents the results of research on the experience of formation, trends, problems and current challenges of scientific knowledge about the place and role of national minorities of Ukraine in the political processes of XX – XXI centuries, namely: a) early XX century, b) during the First World War, Ukrainian revolution and state formation, c) in the interwar period, d) during the Second World War, e) in the Ukrainian SSR 1945-1990, e) in modern Ukraine.

More...

ALFRED DE ZAYAS: The extensive journalistic and historical activity of Ukrainians in exile further confirm the results of the investigations carried out by the War Crimes Bureau in 1941. Roman Ilnytzkyi's study condemns both the murders perpetrated in the Ukraine by the SS and the NKVD murders in Lvov. A collection of documents dealing with the Russian colonialism in the Ukraine devotes an entire chapter to the liquidation of Ukrainian political prisoners by the NKVD, not only in Lvov but also in Vinnitsa, Solotschiv, and a dozen other localities. It reproduces numerous reports of Ukrainian eyewitnesses living today in the United States, Canada, and the Federal Republic of German. // THE AUTHOR: The reader who feels bound by the hitherto generally expressed political opinions about German Ostpolitik must be pointed out from the outset that he is encountering new points of view here. First, the attempt is made to prove that the alleged unity of National-Socialist Ostpolitik did not exist at all. Rather, it was very differentiated and represented by various, often strongly opposing currents. The fateful struggle between Hitler and Rosenberg over the direction of German Ostpolitik had already been fundamentally decided before the outbreak of the German-Soviet war. From the outset, Hitler's victory over Rosenberg greatly jeopardized German political and military success in the East. To the detriment of historical knowledge, no one has pointed out this fact to date, so that the German Ostpolitik has so far been withheld from the public in all its diversity. The prevailing view that German Ostpolitik was based on Rosenberg's plan to divide the USSR into national states is a historical misjudgment. // The reader should also be advised that the historical-political insights on which this volume is based must be viewed as the result of the overall research, i.e. also of the material that is only presented in the second volume.

More...

ALFRED DE ZAYAS: The extensive journalistic and historical activity of Ukrainians in exile further confirm the results of the investigations carried out by the War Crimes Bureau in 1941. Roman Ilnytzkyi's study condemns both the murders perpetrated in the Ukraine by the SS and the NKVD murders in Lvov. A collection of documents dealing with the Russian colonialism in the Ukraine devotes an entire chapter to the liquidation of Ukrainian political prisoners by the NKVD, not only in Lvov but also in Vinnitsa, Solotschiv, and a dozen other localities. It reproduces numerous reports of Ukrainian eyewitnesses living today in the United States, Canada, and the Federal Republic of German. // THE AUTHOR: The author considers the criticism of his view presented in Volume I to be unjustified, namely that no one in modern German and Ukrainian historiography has attempted to present German-Ukrainian political relations in context (see the preface to the first volume). The critic referred the author to Dmytro Doroshenko's work "Ukraine and the Empire" as the account that allegedly accomplished this task. The work of Doroshenko, an internationally renowned Ukrainian historian, is excellent, but its value obviously lies in one completely different field. This work cannot be considered as a history of German-Ukrainian political relations, because it is merely a brilliant presentation of German views on Ukraine over the centuries. The Ukrainian material was not considered at all, because the author had not intended to report on the relations between the two peoples.

More...

The question of Danzig and the Polish "corridor" is still very topical. Despite all that has been written on the subject by experts from the nations directly concerned and those who, belonging to distant countries, have been able to have a relative objectivity, no solution has put an end to the debates. The European Centre for the Carnegie Endowment has recognized the importance of the problem and on several occasions has requested the assistance of technicians and specialists in the field to deal with this subject. It seems interesting today to collect the conferences and the articles thus obtained. // [PUBLISHED in 1932 by the European Centre of the Carnegie Foundation, Department for International Relations and Education (Paris) as issue of the series „Publications for International Conciliation“ ]

More...

In the interwar period, Jews constituted the second largest national minority in the Republic of Poland. The Jewish minority did not have a territorial character, and its representatives could be found all over the country, although their distribution was obviously not even. The so-called Jewish question was one of the most important issues in Poland at that time, affecting all spheres of life. It was certainly the most important issue for the supporters of what was broadly defined as the national camp. Of course, Jewish themes also figured prominently in the national press and journalism of the time – it is no coincidence that the nationalists' message was Judeocentric. The number of publications on the Jewish community rose sharply after 1931 and remained at a high level until the end of 1938. The field of research is therefore extremely broad, not least because of the division of the national camp in the 1930s into numerous groups, often hostile to each other. Opinions that often sound somewhat exotic to the contemporary reader were expressed in the press and political commentary about the large Jewish community in the last period of its existence under the conditions of Polish independence. These opinions allow for a better understanding of complicated Polish-Jewish relations and that now non-existent multinational society.

More...

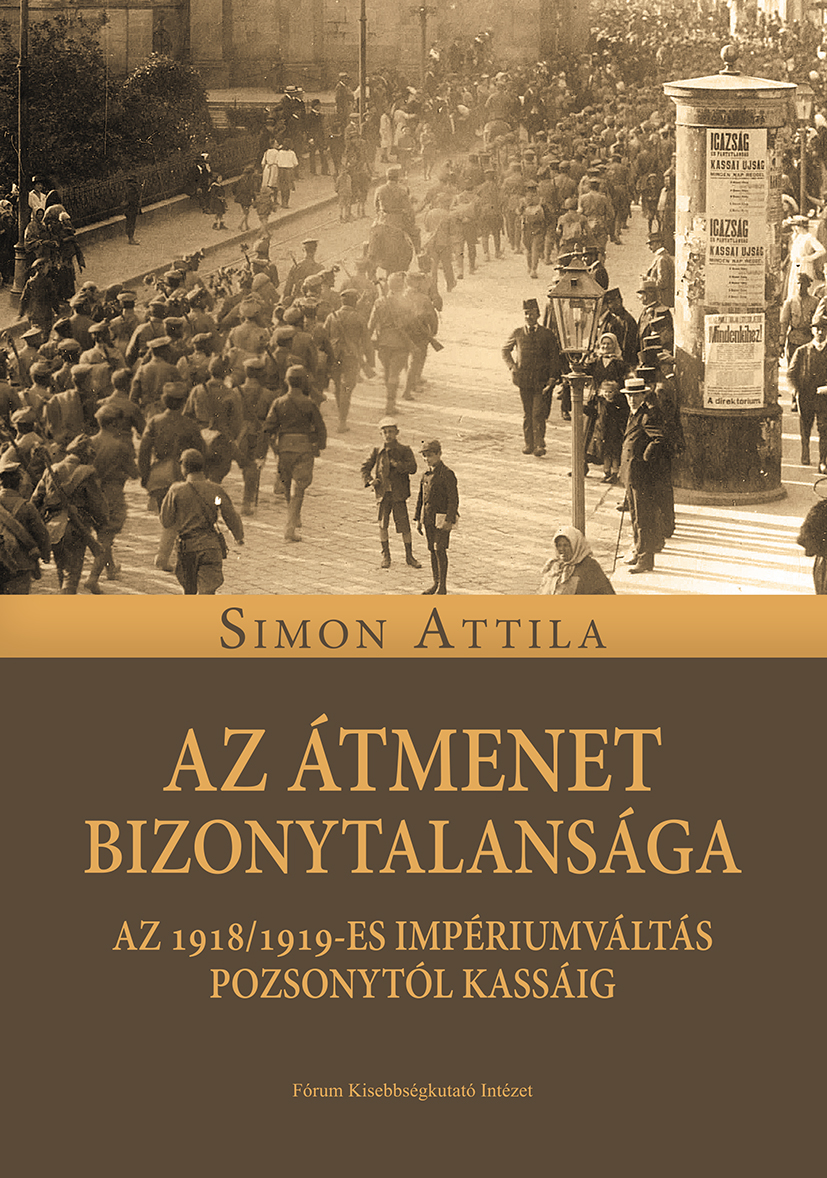

The present volume, which aims to show how the 1918/19 transfer of sovereignty taking place in what is now known as southern Slovakia, summarises the author's research on the subject over the previous four to five years. And although the region is inhabited by Hungarians and Slovaks, the book focuses primarily on the aspirations of the Hungarians living there, the reason of which is not only the numerical superiority of the Hungarians, but also the lack of national self-organisation of the Slovaks living there at the time. As Ondrej Ficeri put it in connection with Košice, it was in vain for the Slovaks to make up a large part of the population there if they had not yet been ethnicised and had not yet formed an organised national community that would have made its voice heard and would have tried to assert its will.The choice of perspective, i.e. the fact that I have focused my analysis primarily on the fate of Hungarians living in the region concerned, unavoidably implies that I am talking about Czechoslovak occupation in the book. For the Hungarians of Žitný ostrov or Gemer, the invasion of Czechoslovak troops was clearly an occupation, and this is how they felt in January 1919 and also when the Czechoslovak army occupied their region for the second time after the withdrawal of the Hungarian Red Army. I myself therefore feel justified in using this term.In the book I try to answer questions such as how the inhabitants of the region under study experienced the period of the Aster Revolution, how they reacted on hearing the news of Czechoslovak occupation, how they received the invaders, how their relationship with the new state power developed, and what events took place in the months of the turn in the region of present-day southern Slovakia.The chapters of the book review the events that took place on this territory from the autumn of 1918 to the autumn of 1919. However, the geographical accents are not evenly distributed, as very little is said about the region east of Košice, due to the lack of relevant sources. The main focus of the research was on regions and especially towns for which I had a wealth of archival and press sources at my disposal. I mainly examined Košice, Komárno, Rimavská Sobota, Lučenec, but also Levice, Nové Zámky and Rožňava. On the other hand, I will only touch on Bratislava, as the rich source material on the city would have been beyond the scope of this volume.Just as the volume is not uniform in its territorial accents, neither is it uniform in its thematic emphases. My attention was primarily directed on the interaction between the Hungarian population and the Czechoslovak power, and in this context on the transformation of life in the region under study, but not in a comprehensive way. Culture, the fate of the theatres, education and schools are just some of the topics that I have not examined. This is partly because they have already been dealt with by more qualified researchers in the subject. Nor did I feel motivated or well-prepared to explore the military history aspects of the subject. Little relevant literature has yet been written on the incorporation of present-day southern Slovakia into Czechoslovakia, or on how the towns here experienced the change of sovereignty. This volume therefore draws heavily on new, previously unexplored archival sources. The history of the political turn in southern Slovakia is both a history of disintegration and a history of construction, as the disintegration of the Kingdom of Hungary is accompanied by the construction of the Czechoslovak Republic. Despite this, the Hungarian literature on Trianon, or the Czech and Slovak literature on the formation of Czechoslovakia, almost always analyses only one of the two processes. The result of this cannot be much else than the incompatibility of the 'grand narratives'. However, the volume presented to the reader is primarily dominated by "small stories", local events and individual destinies, which can only be understood if the disintegration and construction are examined together, in their interrelationship. The contemporary history of Komárno or Košice and the people who lived there is at once the history of the withdrawal of the Hungarian state and the history of the establishment of the Czechoslovak state.The occupation of the region by Czechoslovakia was a more complex process than previously thought, in which the course of events was not necessarily determined by the opposition of the two centres of power, Budapest and Prague, but was influenced at least as much by local forces: the leadership of a given city, taking advantage of Budapest's passivity, the commanders of the occupying troops, and the interaction of these actors.Traditionally, the national aspect has been identified as the central organizing principle of the transfer of sovereignty in southern Slovakia, which assigns the place of the individual actors in contemporary events on an ethnic basis. This, however, is the result of a simplification and misunderstanding of the conditions of the time, and leads to erroneous conclusions such as that the Hungarians in Upper Hungary rejected Czechoslovakia, which, moreover, brought them democracy, solely on the basis of nationalism.But this is a misconception, as is the view that at the time of the change of sovereignty, the old, undemocratic Kingdom of Hungary and the new, democratic Czechoslovakia were opposing worlds in terms of their political systems. There are not only national motives in the attitude of the social democratic groups in Bratislava, in Košice and other areas (and even more so in the case of the German and Slovak workers who went on strike with them) towards Czechoslovakia. For the social democrats, the Aster Revolution was a victory for their earlier aspirations and the democratisation of the country, and the developments after the Czechoslovak occupation were perceived as a process against this. For them, as a manifesto of the workers in Košice indicates, the Czechoslovak army was both a representative of an alien national and class (imperialist) power, and this was what made their rejection so fierce.The two elements of the change of sovereignty in Upper Hungary, the disintegration of the Hungarian state and the establishment of the Czechoslovak state, were an overlapping process. From 29 December 1918, when the Czechoslovak troops occupied Košice, the Czechoslovak state power was already present in the city, but the Hungarian state was also there: its institutions were there, its laws were in force and, above all, its representatives were there. Although the city already belonged to Czechoslovakia, in January 1919 the Czechoslovak presence was stronger in only one segment of the state power: the army. In everything else (institutions, legislation, administration), the Hungarian state seems to be more dominant. And even if its influence is gradually diminishing, while the Czechoslovak presence is gradually growing stronger, it is still present. If this had not been the case, the arrival of the Red Army of the Hungarian Soviet Republic could not have restored the 'Hungarian world' so quickly. The change only accelerates after the second "Czechoslovak occupation", when not only the institutional and administrative takeover is completed, but also the population's acceptance of Prague's power increases.For the above reasons, I believe that one of the most important messages of this volume is to emphasise the phenomenon of transience, even though this concept is not a well-established element in our historiography. However, even if we ignore it, transience is a phenomenon that exists, a phenomenon that marks the in-between periods when the usual order of society ceases to function, or functions only partially, because of some kind of rupture, while a new order is already in the process of being formed. From the point of view of the region examined in this volume, i.e. southern Slovakia, the period of almost a year from autumn 1918 to autumn 1919, during which the role of historical Hungary was taken over by the Czechoslovak state, can rightly be regarded as such a period. The months of transition.The feeling of transience was strongly linked to another feeling, that of uncertainty. For the citizen of southern Slovakia, it was not the fact of change per se that was frightening, but rather the uncertainty that went with transience. The unpredictability of the future. The approach of the Czechoslovak army was also a source of fear, primarily because they did not know what it would bring and what it would entail. And the final demarcation of the borders and the second occupation was a step towards consolidation because it put an end to uncertainty.From this point of view, the gradual abandonment of the rejection of the Czechoslovak state by the Hungarians of southern Slovakia and their pragmatic acceptance was also the result of a desire for certainty and stability that could replace uncertainty. From the summer of 1914 onwards, this was perhaps what they lacked most of all. It is a curious twist of history that it was Czechoslovakia, not Hungary, that gave them stability. Then and there it seemed to be enough to reconcile them to their fate in the long term. It did not take long, however, for it to become clear that this was not enough, that the Hungarians, from Bratislava to Košice, expected more.

More...

Published 1923 in Copenhagen by Rask-Ørsted Fund. In 1921 the administrative committee of the Rask-Ørsted Fund decided to publish a scientific work on the League of Nations, due to the collaboration of authors from different countries. The purpose of this work was to give an account of the origins of the League of Nations, its activity and the divergent opinions which arose in the different countries belonging or not to the League of Nations, on the subject of its importance and its importance. character. The idea of such a work met with the greatest interest among the personalities who participated in the creation of the League of Nations, or who later took part in its work. Representatives of allied and associated states, defeated states and neutral states met here in common work, all inspired by the same desire to contribute to the creation of an international organization based on the principles of peace and justice.

More...

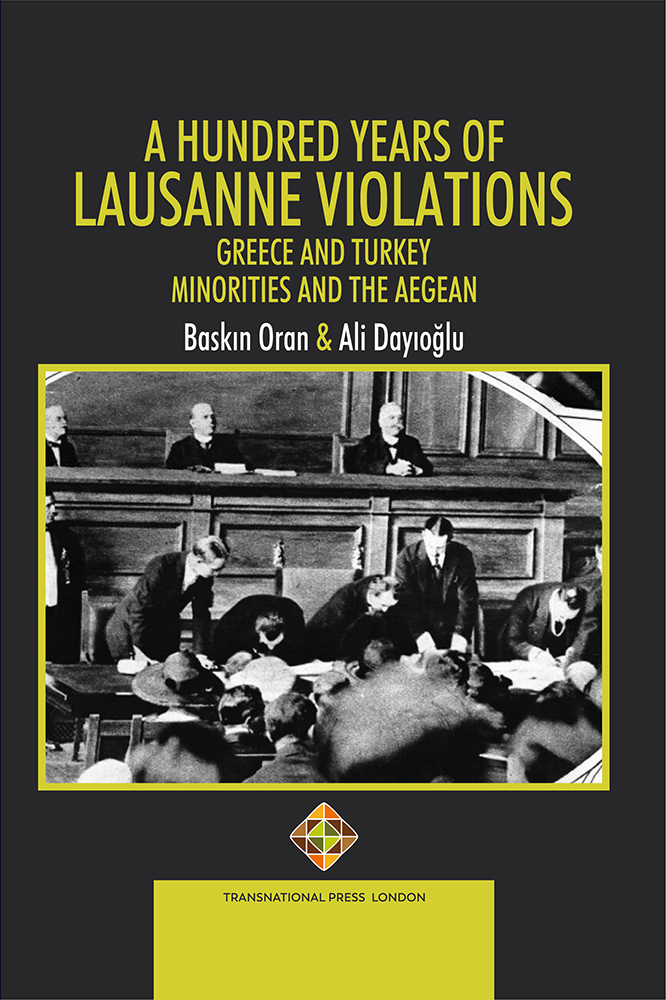

Explore the intricate historical fabric that has woven the complex relationship between Turkey and Greece along the enchanting Aegean Sea. Despite their shared geographic proximity, Greece and Turkey secured their independence in vastly different centuries, with Greece gaining sovereignty in 1830 and Turkey in 1923. Their journeys to nationhood were marred by conflicts, casting a long shadow over their subsequent interactions.Both nations, influenced by the passionate Mediterranean temperament, have engaged in a delicate dance of disputes. Their interactions have often embodied the saying “the pot calling the kettle black,” leading to a series of missteps that occasionally teetered on the brink of armed conflicts in the Aegean. In the process, the welfare of their respective minority communities was often overlooked in the name of protecting their compatriots.Turkey and Greece have resorted to the concept of “reciprocity,” despite its historical association with a cycle of transgressions. This practice, deemed incompatible with international law (as highlighted in Article 60/5 of the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties), further complicates their relations.This insightful book consists of two parts. The first dissects the injustices perpetrated by both nations against their minority populations, meticulously examining the relevant articles of the 1923 Lausanne Peace Treaty and other international texts to expose violations. The second part navigates the turbulent waters of Aegean conflicts, offering impartial insights and arguments, free from national bias.Embark on a journey through a century of history, geopolitics, and international law as we unravel the complexities of Turkey and Greece’s quest for understanding, reconciliation, and peace in the Aegean.

More...