We kindly inform you that, as long as the subject affiliation of our 300.000+ articles is in progress, you might get unsufficient or no results on your third level or second level search. In this case, please broaden your search criteria.

The history of the Jewish community living in the city of Pécs dates back to the 1780s. The religious community was established at the beginning of the 1840s, and some years later, Jewish communities turned into “cultus prefectures”. After this period, these institutions concentrated primarily on the religious life of the community.The Israelite citizens of the country gained their equality before the law in 1867 as a result of the act titled Communitas Judeorum. Afterwards, they started to function as public political institutions, in the frames of which the following issues fell within its competence: cultural and charitable affairs as well as problems related to the administrative and legal cases of the population (approval of divorces, lawsuits etc.). In the case of Pécs, the first statues, which dates back to 1844, did not remained to our era, which means that about the existence of the organisation we have some pieces of information on the bases of certain prefectural records. The content of these document is discussed by József Schweitzer in his monograph on the parish.With the emancipation of the Jewish communities in Hungary, the Jewish civil parishes stopped their functioning, as the public administration of the citizens of Jewish origins became basically identical with the administrational structures of the other nationalities living in the territory of the country. This indicated that civil parishes started to alter into religious communities. As I have already referred to it, the 17th article in 1867 contained provisions about the legal and political equality of the people belonging to the Jewish community. However, it did not gave orders about the religious equality of the Jewish inhabitants. The first Minister of Education and Religious Affairs, baron József Eötvös urged the realisation of reception as well as the religious equality of the Jewish people, but firstly he intended to arrange the structural questions of the Israelite religious community. The result of his aim is the fact that by this time, the altogether 500 thousands of Jewish citizens in Hungary belonged to several hundreds of religious communities.The Izraelita Egyetemes Gyűlés [Israelite Universal Assembly], which started its two-months-long of negotiation in the December of 1848, made it clear, that the Hungarian Jewish community is rather divided. The progressive (the so called neologian) Jewish representatives framed their own structural statute. According to this, the Israelite religious communities dealt “only with tasks related to the religious groups, to the divine services as well as to the issues of education and charity”. However, the validity of this regulation was refused by the conservative wing of the Jewish community, and as a result of this they made efforts to the elaboration of their own structural book of rules. The so called orthodox religious communities, lived according to their “autonomous religious law”, indicating that – on the bases of their own viewpoint – the halakha can be the only legitimate basis of the Jewish religion. In the sense of their interpretation, this is the single law of religion, which is able to determine the life of the faithful Jewish people. Due to the several kinds of interpretations related to the neologian and orthodox wings, neither of these categories can be interpreted as homogeneous. Due to this factor, a smaller group of the religious communities did not join to these organisations, they became to the so called status quo ante groups, and functioned according to their own rules. In 1927, the Hungarian status quo ante religious communities established the Izraelita Hitközségek Országos Szövetsége [National Alliance of the Israelite Religious Groups], whose constitutions had been approved by the Minister of Education and Religious Affairs in the following year.The Israelite Religious Community of Pécs assumed the status quo ante point of view in 1869, however, in practice it followed the neologian ideas, and in terms of its structural organisation, it joined to the congressional parish only in 1924. According to the 42nd article in 1895, the Israelite religion was registered among the legally acknowledged religious groups. This indicated that the possibility of the conversion to the Jewish faith became also legally possible, while the religious communities had a chance to demand for state and local supports. Besides this, the parishes had the opportunity to pay the denominational tax as public tax, which might have been enforced in front of the administrative courtsAnti-Semitism, which started to infiltrate to the national political life with the 20th article of 1920, titled numerus clausus, intensified with the series of discriminative legal acts against the Jewish communities from 1938. The statutes (according to the theoretical literature, altogether 22 anti-Jewish legislations were issued until 1943. As a result of these acts as well as due to the closely interconnected ministerial executive orders, not only the primary rights of those people, who belonged to the Jewish communities or who were legally classified among the Jews, were damaged, but also the legal status of the Israelite Parish was violated. The achievements of the 19th century emancipation and reception proved to be rather fragile. The Hungarian Parliament gradually and imperceptibly eliminated the civic and religious equality of Israelites.Due to the Anti-Semitic legal acts, thousands and thousands of Jewish families had to face with an existential crisis as well as with the extreme poverty in the contemporary Hungary. We do not have accurate statistics about the number of Jews, who lost their Jobs in Pécs, because the written documentation of the religious community of Pécs only discuss the increasing intensity of the charitable work, the situation connected to the retraining courses as well as the organised supports until 1939. In connection with this, we must not forget about the fact, that not only Jewish people lost their jobs, but also those Christian employees, who worked in enterprises of Jewish proprieties. On the one hand, the maintenance of the hospice and the school, where the number of students started to decrease, proved to be extremely difficult. On the other hand, we do not have information about the activity of the charitable organisations. The written documents do not report about the effects of the labour service on the Jewish families, which meant an extremely large burden for the families. It is a generally known fact, that a number of local men died in the eastern front, among the members of the 4th commoner battalion, who left their home for labour service. However, we do not know the exact number of these men, who dies as a result of the horrible and sad trials.After the occupation of the German troops on the 19th of March, 1944, Governor Miklós Horthy remained in his office, and the orders of the government of Ferenc Szálasy, who was nominated by Miklós Horthy, were executed by the majority of the national administrative bodies. As a result of this, Hungarian Jews had to face with the direct life-danger. The chronology and the events of the Hungarian holocaust were elaborated by several scholars, which means that the details of these tragic period of time are generally known. Only 18% of the former Jewish inhabitants of Pécs lived here in the year of 1950, indicating that the majority of them lost their lives or decided to move away from Pécs. Although, the religious community revived, but its strength and prestige was lost.The disenfranchisement of the Jewish people – or of those, who were classified as Jews – was brought to an end by the 200/1945. M. E. order of the “popular democratic” Provisional Government in the March of 1945. The “emancipational and receptional” legislation, which followed the Second World War, was theoretically set in a higher state in the 20th article of the 1949 fundamental law (§54 of this document was on the religious and on the liberty of conscience). However, we cannot talk about a real success connected to this issue (and related to any other issues), as the fundamental law of 1949 declared the Sovietization of the country.The communist and Stalinist dictatorship, which started to develop in Hungary, did not tolerate any kinds of autonomy, and self-evidently, it made efforts to eliminate the autonomy of the different religious groups. The institutional control of the Jewish denominational life – similarly to the other religious groups in Hungary – was practiced by the Állami Egyházi Hivatal [National Church Administration], which was established in 1951. However, the operative leadership remained in the hands of the Magyarországi Izraeliták Országos Szövegtése (MIOI) [National Alliance of the Hungarian Israelites]. The independent scope for action in smaller regional religious communities terminated, but the larger groups, among them the community in Pécs, managed to preserve their relative large autonomy.This present book represents the parochial archives, and its primary aim is to illustrate the parish’s difficult system of functioning with the help of written documentation. The sources published in this volume demonstrate the certain elements connected to the functional structure of the parish, and provide a perfect possibility for the recognition of the everyday life of the society. The reader can be familiar with the daily routine of the Jewish community of the city, while the sources provide a panorama about the positive and negative aspects of the lives of the Jews. The presentation of the history of the Jewish religious community would have been more complex, if the sources of the state archives had been elaborated as well. However, due to the partial and sporadic characteristics of the background research work, I did not made attempts to analyse the documents. The introduction of the antecedents and consequences of the sources, similarly to the people mentioned by their names, is missing from the book. In connection with this, I have to mention that a research work like this is in several cases impossible.The first source, which is published in this book, dates back to 1837, while the “youngest” document was written in 1950. On the one hand, the drastic pressing back of the autonomy of the Jewish religious community dates back to this year. On the other hand, the documents, which were issued after this year – are rather unprocessed. The written sources of the book are naturally primarily letters, which were issued to the parish, as well as documents, which were written by the organisations standing under the authority of the parish i.e. the Chevra Kadisa. These documents can be read in the archives in a relatively small number, mainly in copies. The source selection focuses the content of the issues – instead of the date of their issuing – and as a result of this, the documents are not published in a simple chronological order, but according to thematic units. ------------------------------------------------------------------ Die Geschichte der auch heute lebenden Pécser Judenheit reicht bis in die 1780er Jahre zurück. Die Gemeinde wurde Anfang der 1840er Jahre gegründet.Vor der bürgerrechtlichen Emanzipation der Judenheit (1867) waren die jüdischen Gemeinden (Communitas Judeorum) politische Instanzen, deren Wirkungskreis sich außer den religiösen, kulturellen und wohltätigen Aufgaben der in der Gemeinde lebenden Juden auch auf ihre rechtlichen Angelegenheiten (Bewilligung der Scheidungen, Prozesse im Bereich des bürgerlichen Rechts, usw.) erstreckte.In Pécs ist das erste, aus 1844 stammende Statut nicht mehr vorhanden. Über seine Existenz wissen wir aus dem Vorstandsprotokoll, dessen Inhalt Dr. József Schweitzer in seiner Monographie über die Kultusgemeinde bekannt machte. 1848 gestalteten sich die Gemeinden zu Kultusgemeinden um, ihre Tätigkeit konzentrierte sich grundsätzlich auf das Glaubensleben.Mit der Emanzipation der ungarischen Judenheit wurden die jüdischen Gemeinden aufgehoben, da die Verwaltung der jüdischen Bürger mit der Verwaltung der anderen Bürger identisch wurde: Die Gemeinden formten sich zu Kultusgemeinden um. Der Gesetzesartikel Nr. XVII. im Jahre 1867 sagte die bürgerliche und politische Gleichberechtigung der Bewohner Ungarns israelitischer Konfession aus, die Gesetzgeber entschieden sich aber nicht für die Gleichstellung der israelitischen Konfession. Der Minister für Kultus und Unterricht, Baron József Eötvös, setzte sich für die Rezeption, für die Verwirklichung der konfessionellen Gleichstellung ein, dazu wollte er aber die organisationelle Frage der israelitischen Konfession ordnen. Die etwa halbe Millionen jüdischen Bürger des Landes waren in jener Zeit schon in mehreren Hunderten Kultusgemeinden gruppiert.Im Dezember 1868 setzte sich die Allgemeine Versammlung der Israeliten zusammen, die fast zwei Monate lang tagte. Deren „Ergebnis” war, dass die Spaltung der ungarischen Judenheit auch in organisationeller Hinsicht offensichtlich wurde. Die fortgeschrittenen jüdischen Vertreter (auch Neologen, oder Kongressjuden genannt) schufen ein Statut für ihre eigene Organisation. Demnach waren die israelitischen Kultusgemeinden „ausschließlich Kultusgemeinden”, d.h. Körperschaften, die alleine zum Versehen der „üblichen Aufgaben am israelitischen Gottesdienst, an der Zeremonie, am Unterricht und an Wohltätigkeit” berufen waren. Die Gültigkeit dieses Statuts wurde von der konservativen Judenheit nicht anerkannt, so trachtete sie nach der Schaffung einer eigenen Grundsatzung. Diese Satzung der „autonomen gesetzestreuen” (orthodoxen) Kultusgemeinden betonte die Ausschließlichkeit des Schulchan Aruch. Damit wurde ihrerseits signalisiert, dass sie die Halacha als einzigen legitimen Grund der jüdischen Religion betrachteten, d.h. jenes Religionsgesetz, das den Lebenswandel eines glaubenstreuen Juden gänzlich bestimmt.Wegen der mehreren Deutungsmöglichkeiten der Neologie und der Orthodoxie können selbst die neologen und orthodoxen Richtungen nicht als einheitlich betrachtet werden. Eine kleinere Gruppe der Kultusgemeinden schloss sich an keine Organisation an, sie blieben in der früheren rechtlichen Lage. Diese sind die status quo ante Kultusgemeinden, die sich aufgrund ihrer eigenen Statuten verwalteten. 1927 gründeten sie den Landesverband der ungarländischen „status quo ante” israelitischen Kultusgemeinden, dessen Statut 1928 vom Minister für Kultus und Unterricht bewilligt wurde.Die Pécser Israelitische Kultusgemeinde stand 1869 auf „status quo ante”-Grundlage, praktisch folgte sie aber der Neologie, deren Landesorganisation sie sich erst 1924 anschloss.Aufgrund des Gesetzesartikels Nr. XLII/1895 wurde die israelitische Religion in Ungarn zu gesetzlich anerkannter Religion. Es wurde rechtlich ermöglicht, dass man auch in die israelitische Religion einkehrt, die Kultusgemeinden wurden auf staatliche und kommunale Finanzhilfe berechtigt und die Kirchensteuer der Mitglieder wurde als allgemeine Steuer durch Verwaltungsgerichte einhebbar.Vom Anfang der 1930er Jahre verstärkte sich der Antisemitismus in Ungarn, der mit dem Gesetzesartikel Nr. XX/1920 („numerus clausus-Gesetz”) auf die Ebene der Staatspolitik gehoben wurde. Der Antisemitismus erschien in der Gesetzgebung ab 1938 wieder. Die diskriminierenden Gesetze (die Fachliteratur zählt bis 1943 22 sog. „Judengesetze”) und die Vielzahl der zu diesen herausgegebenen ministerialen Durchführungsverordnungen berührten einerseits die Grundrechte jener Bürger, die zu der israelitischen Konfession gehörten, oder durch das Gesetz als Juden zu betrachten waren, anderseits die rechtliche Stellung der israelitischen Konfession. Die Errungenschaften der Emanzipation und Rezeption der Konfession im 19. Jahrhundert zeigten sich sehr brüchig. Das ungarische Parlament hob zwischen 1938 und 1942 die staatsbürgerliche und konfessionelle Gleichberechtigung der Israeliten fast unbemerkt und allmählich auf.Infolge der judenfeindlichen Gesetze gerieten Zehntausende Familien in Ungarn in existenzielle Krisen und oft in Elend. Wir verfügen über keine genauen Daten, wie viele Menschen in Pécs dadurch arbeitslos wurden (darunter waren auch viele christliche Angestellte der jüdischen Unternehmen). Die Dokumente der Kultusgemeinde berichten bis 1939 über intensiver gewordene Beihilfen, Umbildungskurse und andere organisierte Hilfen. Die von immer wenigeren Kindern besuchte Schule und das Altersheim konnten nur mit großen Schwierigkeiten aufrecht erhalten werden, über die Tätigkeit der Wohlfahrtsorganisationen sind keine Informationen erhalten. Die Pécser Dokumente berichten auch nicht über jene schweren Folgen, die wegen der Abwesenheit des zu kürzerem oder längerem Arbeitsdienst einbezogenen Familienoberhaupts die unversorgt gebliebenen Familien betrafen. Es ist bekannt, dass viele Pécser Männer des IV. gemeinnützigen Arbeitsdienstbataillons infolge der furchtbaren Erprobungen und Grausamkeiten an der Ostfront starben. Über die genaue Zahl der am Arbeitsdienst gestorbenen Pécser Juden stehen keine Informationen zur Verfügung.Nach der deutschen Besatzung des Landes am 19. März 1944 blieb Reichsverweser Horthy in seinem Amt, die Verordnungen der von ihm ernannten und mit der Besatzungsmacht kollaborierenden Sztójay-Regierung wurden vom ungarischen Beamtentum weitgehend durchgeführt. Dadurch geriet die ungarische Judenheit in unmittelbare Lebensgefahr. Die Pécser Ereignisse des Holocaust wurden von mehreren Forschern bearbeitet, die tragischen Ereignisse sind auch in ihren Details bekannt.1950 war die Seelenzahl der Juden in Pécs nur 18 % der Zahl vor der Ghettoisierung und Deportation von 1944. Die anderen starben, oder zogen weg. Die Kultusgemeinde wurde wieder belebt, aber konnte ihr früheres Ansehen und ihre frühere Kraft nicht mehr zurückgewinnen.Im März 1945 wurde die Gültigkeit der Verordnungen, welche die Juden, oder die zu Juden erklärten ungarischen Staatsbürger entrechteten, von der nach dem Krieg gegründeten, sich als völkisch-demokratisch erklärenden provisorischen Regierung mit der Verordnung 200/1945 M.E. aufgehoben. Die Emanzipation und die Rezeption der Konfession in der Gesetzgebungsarbeit nach dem 2. Weltkrieg wurden auf einem höheren Niveau, im Grundgesetz (Gesetzesartikel Nr. XX/1949), im 54. § der Verfassung der Ungarischen Volksrepublik verankert. Theoretisch. Die Verfassung des Jahres 1949 deklarierte praktisch die Sowjetisierung des Landes.Die ausgebaute kommunistisch-stalinistische Diktatur, wie es in ihrer Natur lag, duldete keinerlei Autonomie. So wurde selbstverständlicher Weise auch die Selbständigkeit der verschiedenen Konfessionen aufgehoben. Die Aufsicht über das jüdische Religionsleben, wie auch die über die anderen Konfessionen, gehörte zum Aufgabenbereich des 1951 gegründeten Staatsamtes für kirchliche Angelegenheiten. Die operative Leitung blieb im Wirkungsbereich der MIOI (Landesbüro der ungarländischen Israeliten). Der freie Bewegungsraum der kleineren Kultusgemeinden in der Provinz wurde praktisch aufgehoben, die größeren, wie auch die Pécser Gemeinde, konnten ihre relative Autonomie innerhalb der Rahmen der Landesvertretung der ungarischen Israeliten aufrecht halten.Dieser Band repräsentiert das Archiv der Kultusgemeinde. Er ist bestrebt, mit Hilfe von Dokumenten das komplizierte Gewebe zu zeigen, wie die Kultusgemeinde funktionierte. Die Schriftstücke präsentieren einzelne Elemente ihrer Tätigkeit und ermöglichen Einblicke in die Alltage des Zusammenlebens mit der gesellschaftlichen Umwelt, in deren alltägliche, freudvolle oder düstere Situationen.Die Vorstellung der Geschichte der Kultusgemeinde könnte kompletter sein, wenn die Daten des eigenen Archivs mindestens mit Informationen der Dokumente der staatlichen Archive ergänzt würden.Wegen der fragmentarischen Hintergrundforschungen blieb die analysierende Vorstellung vorerst weg, durch welche ein tieferer Einblick in die Geschichte der Kultusgemeinde gesichert werden könnte. Sowohl die Beschreibung der Vorgeschichte der einzelnen Dokumente, als auch die Beschreibung ihrer – nicht immer erschließbarer – Folgen bleiben also aus und auch die in den Schriftstücken erwähnten Personen werden nicht vollzählig vorgestellt.Das erste Dokument des Archivs ist 1837 datiert. 1950 als Abschlussjahr der Dokumentenauswahl ist theoretisch damit zu begründen, dass in diesem Jahr die Autonomie der Kultusgemeinde drastisch beengt wurde, der praktische Grund ist, dass die danach entstandenen Schriften noch nicht aufgearbeitet sind. Die große Mehrheit der Dokumente sind eingegangene Briefe. Die durch die Kultusgemeinde, oder durch die unter ihrer Aufsicht stehenden Vereine (am meistens von Chewra Kadischa) ausgegebene Schriftstücke sind im Archiv in viel kleinerer Zahl und in Kopie zu finden.Die Auswahl fokussiert nicht auf die Entstehungszeit der Dokumente, sondern auf deren Inhalt, deswegen wurden sie nicht nur rein chronologisch geordnet, sondern in thematische Einheiten. Innerhalb der einzelnen Themen folgen die Schriften der Chronologie.

More...

This book made for the seventieth birthday of Gábor Székely, Professor at the Eötvös Loránd University of Budapest, contains 51 studies. His colleagues wish him Happy Birthday.

More...

Béla Borsi-Kálmán, professor of the Eastern Europe Department of Eötvös Loránd University, has studied the problematics of Hungarian nation formation and national conscience for many years. Within that, he has been mainly investigating the way how the adaptation of the French-type nation-state model took place in the peculiar East-Central European socio-historical and mental context, and how the inherent deficiencies of the former affected the relations of Hungarians with other peoples and nations of the region (especially with Romanians). His research has increasingly convinced him that the key to understanding this intricate system of relations is the group of phenomena that he calls “aristocratic civilianization” (after Bertalan Szemere, Zsigmond Kemény and Zoltán Tóth) that has fundamentally determined our “national character” ever since, and which explains, among others, the successful social integration and nearly perfect Magyarization of the Jewry of Hungary at the end of the 19th century. And perhaps one day it will be the systematic implementation of this “approach” that will bring about the “pacification” of the various segments of the Hungarian nation-body and will allow for the termination and mental surpassing of the disheartening lack of unity at present.

More...

In 1948 in his seminal study “The Jewish Question in Hungary After 1944” István Bibó did draw attention to the role of Hungarian society at large in the implementation of the logic of the Holocaust. Bibó bravely suggested “that the anti-Jewish legislative measures were supported, if not by a clearly visible majority, then at least by a force more massive than their opponents.” What Bibó saw to be a “slippage” from the 1930s onwards resulted in the events of 1944, which Bibó interpreted as evidence of “the moral decline of Hungarian society.” Bibó claims that the opportunities for upward mobility that ‘non-Jews’ seized in 1944 Hungary provided “an appalling picture of insatiable avarice, a hypocritical lack of scruples, or at best cold opportunism in a sizeable segment of this society that was profoundly shocking not only to the Jews involved, but also all decent Hungarians.” This question of postwar remembrance of the Holocaust is of continuing relevance. History is a subject of interest not simply to historians; it has contemporary implications. Whether the Holocaust in Hungary is remembered as a part of or apart from Hungarian history has important implications for the kind of past Hungary remembers. (Tim Cole in Hungary and the Holocaust/Confrontation with the Past/Symposium Proceedings/Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies/United States Holocaust Memorial Museum 2001)

More...

The book contains three Holocaust narratives. They are the recollections of ordinary people whose experiences comprise their sole writing, story and message. The three pieces are not just the narratives of three different fates, but also present three different sociological backgrounds, all characteristic of Hungarian Jewry. And emphasis is placed on three different stages in the Holocaust narrative. Pál Kádár’s story (“A körgyógynapszámos” [The seasonal healer]) presents the life of a village doctor and his family – until their deportation to Auschwitz. The narrative featured in the collection’s title (Kornélia Terner: “Az út szélén” [At the edge of the road]) describes all three stages: the uprooting of a Jewish rural household, the events at Auschwitz, and the emotional difficulties of readjusting to ordinary life under the communist system, as well as the wounds that would not heal and finally the outburst after the last political upturn in 1989. Júlia Fodor-Wieg’s piece “Ezekből az emlékekből fogok élni” [I am going to live on these memories] describes the Holocaust as it was experienced by upper-middle-class Jews. The other great Hungarian narrative on the Holocaust is the hunt for men in the jungle of Budapest. The focus of her story continues until her departure from Hungary in 1957. She tells of the demise of a plundered Jewish middle-class, a great and credible document of the will and capacity for life. All three pieces bring us closer to ordinary people who are also heroes. Visual records of the destroyed world illustrate the book. In the epilogue The Holocaust as Narrative, János Kőbányai, who collected the memoirs, analyses and typifies the Hungarian Holocaust as a historical and cultural phenomenon on the lines of Imre Kertész’s “great narrative”.

More...

Sándor Bacskai´s „The First Day“ – as the first volume – begins with the golden age of the Jewish orthodoxy and ends in the time of returning from the forced labor camps, concentration camps.

More...

The story of a Jewish boy who survived the Holocaust. The book shows that for Jews there was no effective system of coping with the Nazi oppression. Neither connections nor money could save them – the survivors had to be extremely lucky in the first place and have a tremendous will of survival. The testimony is supplemented with the description of an amazing process: Auschwitz could have become a point of mass emigration of the Jews and not a site of extermination. The present fourth edition of the book contains documents fully confirming the truthfulness of that thesis. These memoirs are expanded with the post-war history of the Schönker family, including their struggle with the secret political police persecuting Jewish entrepreneurs (1945–1955).

More...

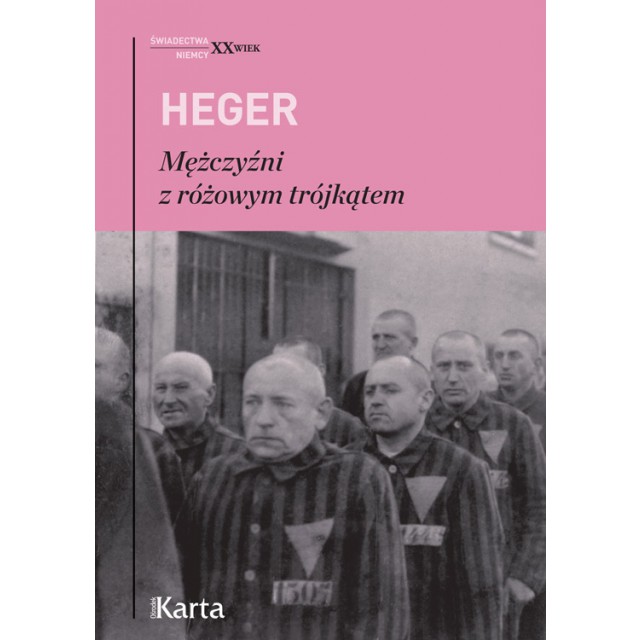

Memoirs of a former inmate of Nazi concentration camps who was persecuted for his homosexual orientation. Memoirs of Heinz Heger (pen name of Josef Kohout) are considered unique not only because of breaking a taboo but also because of the description of the suffering of that group of victims which was persecuted also after World War II. Section 175 survived in the GDR and FRG until the end of the 1960s. The “extension” of persecution blocked the struggle of former inmates for compensation and the status of a group of victims. Heger started to be persecuted in 1939 with his imprisonment. In 1940, he was moved to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Less than six months later – to KL Flossenbürg, where he was put to a “special” block, where inmates with the pink triangle were isolated. The man was liberated by the US Army during a death march from the Flossenbürg concentration camp to KL Dachau. The book, an account by Heinz Heger titled Die Männer mit dem rosa Winkel, was published in Germany in 1972, in Great Britain in 1993, and in France in 2002.

More...

The original version of the testimony of Calel Perechodnik, a resident of Otwock, a Jewish policeman at the local ghetto. The book is an accusation of the German people, and, at the same time, the Polish and Jewish people. The author assumes a great portion of responsibility for the death of his wife and a two-year old daughter. He outlines the figures of Poles and Jews known to him. He ruthlessly reveals their weaknesses and vices which had led to social consent for the occurrence of such inhumane situations. The Confession was written in 1943, but its author did not live to see the liberation.

More...

The book approaches the history of Latvia from the earlist traces of human habitat to the present. It is a rather detailed analysis blending methods of political history, social history, economic history, international relations, nationalities studies, etc. and tackling the main lines of history of all communities living or which have lived in Latvia.

More...

The author analyses and interprets selected prose and dramatic works of Marian Pankowski in reference to areas of contemporary humanities: Holocaust studies, trauma studies, gender studies, memory studies and animal studies. She draws attention to Pankowski’s concentration camp experience. The author addresses themes most often explored in Pankowski’s works: the Holocaust, the writer’s attitude toward the body and corporeality, his obscene aesthetics and his Gombrowicz-like distance toward the national myths.

More...

Upravo doneti Zakon kojim se rehabilituju svi “ideološki” protivnici komunizma, počinje sa datumom od 6. aprila 1941. što je istovremeno i njegov najzanimljiviji deo. Imali smo priliku da slušamo predlagače i zagovornike zakona1 koji su svojom srčanom odbranom ratnih “ideoloških” protivnika komunizma, nedvosmisleno potvrdili da je čitava stvar i smišljena isključivo zbog njih, a da ih oni posle 1945. ustvari i ne zanimaju, odnosno, da su samo “kolateralna šteta” pokušaja rehabilitacije kvislinga iz vremena Drugog svetskog rata. Saopštili su nam i da bi čitav komunistički period trebalo jednostavno proglasiti zločinačkim čime bi, misle oni, po automatizmu bili rehabilitovani svi njegovi “ideološki” protivnici, a oni ratni proglašeni borcima za pravednu stvar. Zato možemo očekivati da će (kao što se već desilo sa četnicima) ovog puta “demokratama” biti proglašeni nedićevci i ljotićevci, pa će po automatizmu “demokrate” postati i balisti, hortijevci, ustaše, i na kraju, sam nemački Rajh. Svi oni zaista jesu bili “ideološki” protivnici komunizma, ali je, sasvim sigurno, Hitler bio najveći. Zato nije slučajno danas, njihov “ideološki” antikomunizam i početak i kraj svake argumentacije, uz prećutkivanje da su kao protivnici komunizma bili i aktivni protivnici celokupne antihitlerovske koalicije čiji je komunizam bio sastavni deo. Prećutkuje se i da je njihov “ideološki” antikomunizam u tadašnjem shvatanju pojma podrazumevao veličanje nacizma, antidemokratiju, i na prvom mestu, antisemitizam, “slučajno”, baš u vreme kada su milioni Jevreja ubijani u “Velikom Nemačkom Rajhu”.

More...

Stanovišta o novim političkim pokretima i idejama, a to se posebno odnosi na fašizam, zastupana pre nego što su se ispoljile sve posledice njegovog delovanja, višestruko su značajna. Iako mogu danas da izgledaju anahrona, ona pružaju odgovor na pitanje da li je postojala kultura razumevanja i predviñanja, odnosno, da li je svest o značaju odreñenih zbivanja vodila ispravnom zaključivanju o mogućim posledicama ili je, prateći ideološke želje savremenika, vodila zaključcima manje ili više udaljenim od realnosti. Pokazuju i sa kakvim je predznanjima šira javnost dočekivala prelomna zbivanja, a mogu i da ukažu na razloge dijametralno suprotnih aktivizacija pojedinaca i grupa u njima. Isti istorijski kontekst je tridesetih godina stvarao dijametralno različite tekstove. Ono što u metodološkom smislu može biti ograničavajući faktor kod ocenjivanja vrednosti jednog izvora, sama činjenica da je tekst pisan sa namerom da odmah bude i dostupan javnosti, što znači da je sadržavao upravo ono što je u tom trenutku za autora bilo poželjno viñenje, u analizi koju zanimaju upravo stavovi savremenika ima najveću vrednost. Zato se razlika izmeñu tekstova nastalih u istom kontekstu ne može objasniti nepoznavanjem „činjenica“ već suprotnom vizurom iz koje su posmatrane, a koja je uslovljena različitim ideološkim načelima koja su autore vodila. U tom smislu, tekstovi savremenika o zbivanjima koja su u toku i sami se moraju posmatrati kao „delovi procesa“ 7 koji se analizira.

More...

MIXER, Olivera Milosavljević: Slučaj profesora Blumentala; CEMENT, Dragoljub Stanković: Lakoća providnog; ARMATURA, Srđan Nastasijević: Umri muški u Zemunu, Saša Ćirić: Kosovo - kretenski triangl; VREME SMRTI I RAZONODE, Tomislav Marković: Simpathy for the Amfilohije; BULEVAR ZVEZDA, POPOVIĆ PERIŠIĆ, Nada; BLOK BR. V, Kosmoplovci: Idemo dalje

More...

Prošlog četvrtka, kada je dopisnicima iz Kijeva već ponestalo jezivih opisa za sukobe na Majdanu posle 18. februara, koji je samo nakratko važio za najkrvaviji dan u istoriji nezavisne Ukrajine – dopisnici iz Silicijumske doline javili su da je Jan Kum preko noći postao milijarder. Ukrajinski Jevrejin koji je 1992. sa mamom i bakom, jer za očevu kartu nije bilo para, otišao iz neke blatnjave selendrice kod Kijeva čim je postalo moguće napustiti istočni lager, Kum je ugovor onaj vrednijoj akviziciji startap projekta u istoriji internet industrije potpisao na vratima socijalne službe u Kaliforniji, pred kojim je godinama stajao u redu za bonove za hranu.

More...

Ovih dana i ja, kao i mnogi drugi, razmišljam o Ukrajini. Posebno o tome kako njima, građanima (sic!) Ukrajine, polazi za rukom nešto na čemu im mnogi građani Rusije zavide. Njima već danima uspeva da masovno i uporno brane svoje građansko dostojanstvo, potvrđuju svoju građanski odgovornost i svoju društvenu zrelost.

More...

Ultraortodoksna zajednica (haredim) oduvek izaziva žestoke kritike sekularnih izraelskih građana. Njihova različitost, zatvorenost, njihovi neobični običaji i vođe koji mumlaju molitve, staromodna odeća, odnos prema ženama, odbijanje da rade i služe vojni rok (ne daj bože!), to što njihova deca uče po odvojenom školskom programu – sve to neprekidno doliva ulje na vatru. Mržnja prema njima je slepa, preterana i neprikladna. Ponekad se graniči sa antisemitizmom. Reči koje se izgovaraju protiv njih su ružne i nepristojne, među najgorima koje se čuju u javnom prostoru.

More...

The Romanian Section of the World Jewish Congress (henceforth: WJC) conducted a national survey among the Jewish survivors of the Holocaust in 1946. The objective of the survey was to assess the human and material losses and record the grievances suffered by the surviving Jewish population. In addition to this the statistical data gathered was intended to serve as a basis during the negotiations of the Peace conference ending World War II and for compensation claim. This study analyses the survey and its results regarding three towns from Northern Transylvania (Cluj, Carei and Oradea) which belonged to Hungary during the Holocaust period.

More...

The publication serves as a support for secondary school teachers for the development of activation teaching in history.

More...