Keywords: "Vlachs"; Romanians; Serbia; east; Yugoslavia; census; Romania; ethnicity; language; representative bodies; culture; interethnic relations;

(Serbian and Romanian edition) Uoči popisa stanovništva u Saveznoj republici Jugoslaviji, odnosno u Republici Srbiji, neophodno je detabuizirati tzv. “vlaško pitanje”. Naime, postoji neodrživo nasleđe u tumačenju forme i sadržaja ovoga pitanja. U ovoj brošuri Forum za kulturu Vlaha (na vlaškom: Forumu' pėntru Cultura a Rumâńilor) govori o Vlasima u istočnoj Srbiji, tačnije rečeno između Morave, Dunava i Timoka, kao produktu romanizacije, a ne o nekoj kategoriji “vlaha” koji nemaju takav etnički predznak. Nekih drugih “vlaha” i nema na pomenutom prostoru, sem ako se ne izmisle. Romanizacija kao fenomen započeo je sa rimskim zaposedanjem Ilirika, na istočnoj obali Jadrana, u III veku pre nove ere, a na prostorima gde i danas žive na jezicima nepripadnika tzv. Vlasi, posle 168. godine p.n.e. Tada je nestala antička Makedonija da bi se na jugu Balkanskog poluostrva instaliralo Rimsko carstvo. Ovo carstvo se u prvom veku nove ere proširilo do Dunava, a sa Trajanovim osvajanjima, od 101. do 105. godine nove ere, i preko Dunava. Tako je nastala Trajanova Dakija koja opstaje do 271. godine n.e. Te godine, iz strateških razloga, po odluci imperatora Aurelijana, Rimljani i deo romanizovane populacije napuštaju prostore severno od Dunava, pa se južno od Dunava uspostavlja Aurelijanova Dakija. Ovde se nastavlja proces romanizacije autohtone populacije Tračana, kao i onih koji su iz različitih motiva došli ili su dovedeni sa raznih drugih strana Rimske imperije. Verovatno je taj proces osnažen i promenom u rimskoj legislaciji kroz unifikaciju statusa rimskih građana Ediktom imperatora Karakale 212. godine. Tako su se u jugoistočnoj Evropi rodili “Vlasi”. Zbog intenzivnosti tog procesa na karpatsko-podunavskom prostoru, istorijski gledano ovo šire područje se može označiti prostorom gde su se pojavili “Vlasi”, tj. to je “vlaški matični prostor”. U današnje vreme, imajući u vidu istorijske i antropološko-kulturološke promene koje su se dogodile u proteklih dva milenijuma, tako se može kvalifikovati samo današnja Rumunija. U etnogenetskim procesima, za koje se smatra da su se okončali od VII-X veka, ovaj balkanski element je dobio novo ruho. Njegovom uobličavanju u novi etnički entitet doprinos su dali i Sloveni u svom pomeranju na Balkanskom poluostrvu. U toku ili pri kraju takvog procesa došlo je do razdvajanja severnog i južnog ogranka ove populacije, koja se pod imenom Vlaha pominje u istoriji 976. godine, povodom pogibije Davida, brata cara Samuila. Još iz najranijih vremena Germani su susedne Kelte i Rimljane nazivali WALHOS. Kasnije se ova etnička odrednica suzila na romanizovane populacije koje su dobile svoju latinsku identifikaciju ROMANUS. Od ova dva naziva nastale su hipostaze koje poznajemo i u današnje vreme, uključujući i slovenski naziv “Vlah, Vlasi”, odnosno “vlaški”, na rumunskom književnom jeziku “Român, Români”, na rumunskom narodnom govoru “Rumân, Rumâni” (kao npr. u Dosoftejevom Psaltiru u stihovima na rumunskom iz 1673., te u Šerbanovoj Bibliji na rumunskom iz 1688., itd.), naime na muntenskom, krišanskom, maramureškom, moldavskom i banatskom narečju rumunskog jezika.

More...

Keywords: Serbia; minorities; legal regulations; international law; federal act; rights and freedoms; native language; education; Vojvodina; central Serbia; political parties; judiciary;

October 2000 political changeover did not produce the fundamental break with Milosevic's policy. There are numerous examples thereof, notably as regards Republika Srpska, Kosovo and Montenegro. Insistence on that orientation in the face of factual defeat had a negative impact on status of inter-ethnic relations in Serbia proper. National policy aiming at creating an ethnically pure Serb state ended with a catastrophic balance: hundreds of thousands of dead, several million displaced persons and refugees. In the past decade minorities, notably Croats (during the war in Croatia), Bosniaks (during the war in B&H) and Albanians (during the whole decade) bore the brunt of "ethnic-cleansing" policy. By extension, relations between the majority people and some minorities were exacerbated. In the meantime minorities have radicalised their stands and are waiting for resolution of their problems by dint of international community brokerage. Most conspicuous example of the aforementioned was South Serbia, in which the danger of conflict spill-over was great for a while. But thanks to NATO and other international organisations actions and efforts tension has eased and cooperation and revival of economy have been initiated owing to enormous political and financial support of the West. Serbia has entered the period of facing up to difficult and long-term consequences of nationalistic and war policy of the former regime. The entire society has been devastated, and institutions of system destroyed. Long wars, international isolation and bombardment campaign have impacted the general social mood, which is marked by high intolerance, xenophobia, anti-Semitism and emergence of neo-Nazi groups. This is all due to the political vacuum and absence of vision of Serbia's future. Such a general atmosphere affects national minorities, who feel increasingly threatened. The last census, according to unofficial information, indicates that Serbia remains a markedly multi-ethnic country. This may be explained by massive emigration or brain-drain of young and educated Serbs. About 400,000 refugees from Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo, contrary to some expectations, have not to a larger extent changed the demographic structure of the country. Despite emigration of minorities, their percentage remained the same, in view of de-assimilation of Vlahs and Romany (they stopped identifying with Serbs). This means that the minority issue would remain the hot issue, notably if the nationalistic block continues to persist on realisation of ethnically pure state. Some ethnic communities have been territorially homogenised, hence some of them, in some areas constitute the majority population. Some national minorities, notably Albanians, Bulgarians, Croats, Hungarians, Bosniaks/Muslims, and Romanians inhabit border areas. Thus their territorial homogenisation is a complex political fact. Despite current authorities efforts to fine-tune national minorities-related domestic legislation to the European standards, situation in that regard is slowly changing because of badly impaired inter-ethnic relations in the last decade. Ethnic distance had been increased, but as of late it started dwindling, but not everywhere and not with respect to all minorities.

More...

Keywords: Serbia; minorities; legal regulations; international law; federal act; rights and freedoms; native language; education; Vojvodina; central Serbia; political parties; judiciary;

October 2000 political changeover did not produce the fundamental break with Milosevic's policy. There are numerous examples thereof, notably as regards Republika Srpska, Kosovo and Montenegro. Insistence on that orientation in the face of factual defeat had a negative impact on status of inter-ethnic relations in Serbia proper. National policy aiming at creating an ethnically pure Serb state ended with a catastrophic balance: hundreds of thousands of dead, several million displaced persons and refugees. In the past decade minorities, notably Croats (during the war in Croatia), Bosniaks (during the war in B&H) and Albanians (during the whole decade) bore the brunt of "ethnic-cleansing" policy. By extension, relations between the majority people and some minorities were exacerbated. In the meantime minorities have radicalised their stands and are waiting for resolution of their problems by dint of international community brokerage. Most conspicuous example of the aforementioned was South Serbia, in which the danger of conflict spill-over was great for a while. But thanks to NATO and other international organisations actions and efforts tension has eased and cooperation and revival of economy have been initiated owing to enormous political and financial support of the West. Serbia has entered the period of facing up to difficult and long-term consequences of nationalistic and war policy of the former regime. The entire society has been devastated, and institutions of system destroyed. Long wars, international isolation and bombardment campaign have impacted the general social mood, which is marked by high intolerance, xenophobia, anti-Semitism and emergence of neo-Nazi groups. This is all due to the political vacuum and absence of vision of Serbia's future. Such a general atmosphere affects national minorities, who feel increasingly threatened. The last census, according to unofficial information, indicates that Serbia remains a markedly multi-ethnic country. This may be explained by massive emigration or brain-drain of young and educated Serbs. About 400,000 refugees from Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo, contrary to some expectations, have not to a larger extent changed the demographic structure of the country. Despite emigration of minorities, their percentage remained the same, in view of de-assimilation of Vlahs and Romany (they stopped identifying with Serbs). This means that the minority issue would remain the hot issue, notably if the nationalistic block continues to persist on realisation of ethnically pure state. Some ethnic communities have been territorially homogenised, hence some of them, in some areas constitute the majority population. Some national minorities, notably Albanians, Bulgarians, Croats, Hungarians, Bosniaks/Muslims, and Romanians inhabit border areas. Thus their territorial homogenisation is a complex political fact. Despite current authorities efforts to fine-tune national minorities-related domestic legislation to the European standards, situation in that regard is slowly changing because of badly impaired inter-ethnic relations in the last decade. Ethnic distance had been increased, but as of late it started dwindling, but not everywhere and not with respect to all minorities.

More...

Keywords: Serbia; media; magazine; "Vreme"; polemics;

More...

Keywords: Serbia; prison; KPZ; VPD; district prison; Niš; Požarevac; Sremska Mitrovica; Belgrade; Padinska Skela; Ćuprija; Šabac; Sombor; Kruševac; Valjevo; Novi Sad; quality of life; security; lawfulness; social resettlement; outside world contact; personnel;

(Serbian edition) Throughout the totalitarian rule of the regime of Slobodan Milošević and his henchmen, which lasted for over a decade, the country’s prisons remained shut to public scrutiny. Information about the state of human rights of the prisoners and the conditions in which they served their sentences was the exclusive privilege of the state authorities directly involved and of the individuals and institutions concerned with the matter for purposes of scientific research. The question of prisoners’ human rights was completely marginalized by war, crimes, economic hardship and daily violations of citizens’ human rights and freedoms up to 5 October 2000. For many a convict, being locked away to serve a sentence of imprisonment did not mean mere deprivation of liberty for a set period of time, but also the start of a cruel struggle for survival in the gloom of lawlessness, corruption, torture, inhuman conditions and society’s total lack of interest in his or her life behind bars. It was only after widespread prison rioting broke out in November 2000 that the public’s attention was drawn to the conditions in which the prisoners served their sentences. The prisoners put out announcements throwing light on the substandard and inhuman conditions prevailing in Serbia’s penitentiaries and prisons. During the riots, groups and individual prisoners made statements complaining that the prison conditions were far below the levels set by relevant international standards and domestic prison rules. The prisoners alleged serious violations of their physical and psychological integrity, humiliating and degrading treatment, unjust punishment and general arbitrary treatment by prison personnel. They complained of, among other things, torture by beating, lack of minimum personal hygiene facilities, absence of medical treatment and health care, and corruption among prison administrative staff. Some of the allegations and complaints were partly confirmed by competent officials of the Ministry of Justice. As a palliative for the utterly unsatisfactory prison conditions, federal and republican amnesty laws were duly introduced to be finally adopted respectively on 26 February 2001 and 13 February 2001. Nonetheless, although a number of convicts were fully amnestied and a percentage of sentences commuted, the conditions in which prisoners served their sentenced remained unchanged. In addition to the factors mentioned above, the inhuman conditions in Serbia’s prisons endured and multiplied also owing to the country’s isolation of many years, during which time no international organization other than the International Red Cross was granted access to its prisons. Domestic non-governmental organizations were also kept at arm’s length and only rarely allowed to see what went on inside. In view of the circumstances enumerated above, it was clearly necessary to introduce continuous monitoring of prisons by an independent, non-governmental institution in order to obtain a realistic picture of the prison conditions. The new government is aware that admission to the Council of Europe and to other international organizations depends in part on the conditions in which sentenced persons serve their prison sentences, as well as that the public must be informed about those conditions. So, after presenting the concept and objectives of the Prison Monitoring project, the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia was granted permission in May 2001 to visit institutions for the enforcement of criminal sanctions. This meant that for the first time in the history of this state an NGO could apply for and be granted permission to visit places of detention, custody and imprisonment without any restrictions, to interview prisoners with no personnel being present, and to talk to personnel without the presence of administration officers. Between June 2001 and October 2003, the Helsinki Committee paid a total of twenty-one visits to institutions for the enforcement of sanctions entailing the deprivation of liberty. During the period covered by this report (April 2002 to October 2003) the Helsinki Committee visited twelve institutions (one maximum-security prison, two closed prisons, three open prisons, two district prisons, one psychiatric prison, one reformatory, and one juvenile prison). In launching the project, the Helsinki Committee was principally guided by Article 64 of the European Prison Rules which states: ‘Imprisonment is by the deprivation of liberty a punishment in itself. The conditions of imprisonment and the prison regimes shall not, therefore, except as incidental to justifiable segregation or the maintenance of discipline, aggravate the suffering inherent in this.’ The Helsinki Committee hopes that its efforts to complete the project and publish this book will make a small but valuable contribution towards achieving this goal.

More...

Keywords: Serbia; prison; KPZ; VPD; district prison; Niš; Požarevac; Sremska Mitrovica; Belgrade; Padinska Skela; Ćuprija; Šabac; Sombor; Kruševac; Valjevo; Novi Sad; quality of life; security; lawfulness; social resettlement; outside world contact; personnel;

(English edition) Throughout the totalitarian rule of the regime of Slobodan Milošević and his henchmen, which lasted for over a decade, the country’s prisons remained shut to public scrutiny. Information about the state of human rights of the prisoners and the conditions in which they served their sentences was the exclusive privilege of the state authorities directly involved and of the individuals and institutions concerned with the matter for purposes of scientific research. The question of prisoners’ human rights was completely marginalized by war, crimes, economic hardship and daily violations of citizens’ human rights and freedoms up to 5 October 2000. For many a convict, being locked away to serve a sentence of imprisonment did not mean mere deprivation of liberty for a set period of time, but also the start of a cruel struggle for survival in the gloom of lawlessness, corruption, torture, inhuman conditions and society’s total lack of interest in his or her life behind bars. It was only after widespread prison rioting broke out in November 2000 that the public’s attention was drawn to the conditions in which the prisoners served their sentences. The prisoners put out announcements throwing light on the substandard and inhuman conditions prevailing in Serbia’s penitentiaries and prisons. During the riots, groups and individual prisoners made statements complaining that the prison conditions were far below the levels set by relevant international standards and domestic prison rules. The prisoners alleged serious violations of their physical and psychological integrity, humiliating and degrading treatment, unjust punishment and general arbitrary treatment by prison personnel. They complained of, among other things, torture by beating, lack of minimum personal hygiene facilities, absence of medical treatment and health care, and corruption among prison administrative staff. Some of the allegations and complaints were partly confirmed by competent officials of the Ministry of Justice. As a palliative for the utterly unsatisfactory prison conditions, federal and republican amnesty laws were duly introduced to be finally adopted respectively on 26 February 2001 and 13 February 2001. Nonetheless, although a number of convicts were fully amnestied and a percentage of sentences commuted, the conditions in which prisoners served their sentenced remained unchanged. In addition to the factors mentioned above, the inhuman conditions in Serbia’s prisons endured and multiplied also owing to the country’s isolation of many years, during which time no international organization other than the International Red Cross was granted access to its prisons. Domestic non-governmental organizations were also kept at arm’s length and only rarely allowed to see what went on inside. In view of the circumstances enumerated above, it was clearly necessary to introduce continuous monitoring of prisons by an independent, non-governmental institution in order to obtain a realistic picture of the prison conditions. The new government is aware that admission to the Council of Europe and to other international organizations depends in part on the conditions in which sentenced persons serve their prison sentences, as well as that the public must be informed about those conditions. So, after presenting the concept and objectives of the Prison Monitoring project, the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia was granted permission in May 2001 to visit institutions for the enforcement of criminal sanctions. This meant that for the first time in the history of this state an NGO could apply for and be granted permission to visit places of detention, custody and imprisonment without any restrictions, to interview prisoners with no personnel being present, and to talk to personnel without the presence of administration officers. Between June 2001 and October 2003, the Helsinki Committee paid a total of twenty-one visits to institutions for the enforcement of sanctions entailing the deprivation of liberty. During the period covered by this report (April 2002 to October 2003) the Helsinki Committee visited twelve institutions (one maximum-security prison, two closed prisons, three open prisons, two district prisons, one psychiatric prison, one reformatory, and one juvenile prison). In launching the project, the Helsinki Committee was principally guided by Article 64 of the European Prison Rules which states: ‘Imprisonment is by the deprivation of liberty a punishment in itself. The conditions of imprisonment and the prison regimes shall not, therefore, except as incidental to justifiable segregation or the maintenance of discipline, aggravate the suffering inherent in this.’ The Helsinki Committee hopes that its efforts to complete the project and publish this book will make a small but valuable contribution towards achieving this goal.

More...

Keywords: Serbia; principles; practices; ethnic minorities; language; education; rights and freedoms; law; assimilation; council of europe; religion; media;

More...

Keywords: anti-war discourse;serbian nationalism;hague tribunal; balkanism; serbian-albanian relations; kosovo conflict;

More...

Keywords: sfr yugoslavia; eu integration; kosovo conflict; serbian-albanian relations;human right in Serbia;anti-war discourse;

More...

Keywords: Serbia; nationalism; totalitarianism; modernization; ideology; dialogue; politics; democratization; decadence; BIH; Croatia; intellectuals; political regime; Vojvodina; minorities; media; intellectuals; war; national programs; Marina Cvetajeva; gender;

(ANOTHER SERBIA) Every Saturday for a period of two months, from the beginning of April till the end of June 1992, sessions organized by the Belgrade Circle were held at the Student Cultural Centre in Belgrade. At these sessions, ten in all, intellectuals, members of the Belgrade Circle and their quest – distinguished writers, scientists, artists, journalists, film and theatre directors, architects, actors, interpreters – expressed their own views of another, radically different Serbia. In times of anguish and affliction, the meetings, attended by a large assembly of listeners experiencing a kind of moral purification, were nonetheless imbued with a frail hope that there still might be a chance for a turn in events. With a desire to present ideas, opinions and sensations shared by the participants of the Belgrade Circle sessions to a much larger audience, the reading public, and to preserve them, because of their merit, in a more lasting form, discussions of over eighty intellectuals were compiled to form this book. In the meantime, the overwhelming disaster has reached its climax: »The Bosnian War«, still raging with no feasible way out as yet, exploded and blazed up like fire. The Belgrade Circle participants, distressed and abashed at the display of all those real or imagined evil deeds, so eagerly reported by the portentous heralds of death voiced hitherto often deeply hidden and silent feelings and thoughts about their burdensome disgust at the plague gripping and afflicting us all. Each participant contributed in his or her own way – rigorous scientific analysis, artistic susceptibility, eyewitness accounts, or simply. A public-minded desperate wail – to the shaping of one new, public opinion, the one that stirred in that sad Spring of ’92 and rebelled against the general fear, animosity, devastation, extermination, ethnic cleansing, forcible population exchanges... All those responsible and public-minded citizens, holding different political opinions, some members of various political parties, with incomparable personal experiences, varied professional interest and often of »objectionable« national origin, showed, however the will to insert tolerance among the basic principles of a humanized way of fife. But, in spite of the pronounced differences, their common aim, discernable in each and every speech imported to the audience, was to finally establish a community based on simple but as yet still unattainable ideals such as peace, freedom, tolerance and justice in place of degrading political, national and religious exclusiveness. Participants focussed their attention on various aspects of the problem: some analysed the roots of hatred and evil; some indicated the disastrous consequences of irresponsible national myth revivals; others warned of menaces yet to come unless we see reason in time. Some were stern, others witty and others still perhaps too prone to pathos, but they were all deeply concerned, and, as it unfortunately turned out, correct in predicting subsequent events. Therefore, individuals who take no notice of current, official policy and who have for a long time now tenaciously refused to render their talent and knowledge to the needs of the authorities, gathered round a project titled »Another Serbia«. Instigating a state of war and providing alleged erudite justification for the necessity of mutual extermination in the name of some noble goals, vague even to the very massacre executors, must not and cannot be the vocation of anyone who considers him or herself an »intellectual«, or earns a living acting as one. Hence, all session participants had but one desire: to mark out a path that may lead into a more promising future, to another, different, better and happier Serbia. »Another Serbia« soon became the synonym of resistance to fabricated lies, nationalistic madness, criminal war, a fascist holocaust, senseless destruction of villages and cities. Thanks are also due to the daily newspaper »Borba« which regularly reported on the Belgrade Circle Saturday sessions, and published a number of contributions presented there... We hope that the Another Serbia we all aspire to be easily discernable in the collection of essays presented in this book. The reader who hopes to find traces of at least some political program will be gravely disappointed. At present, when politics have poisoned the very soul of so many men of letters and knowledge, and when, among the most violent oppressors, in the ranks of all mortal enemy groups, one finds so many proud bearers of scientific degrees, who may actually be designated as men of unmerited and easily squandered reputation, it has become somewhat indecent to praise »intellectual pursuits«. The Belgrade Circle was, however, founded early in 1992 with the aim of retrieving dignity – another dangerous quality! – to public speech and conceived plans of action for the benefit of truth. We do not take an elitist position and stand indifferently above the crowd. On the contrary, being deeply involved and concerned, we place ourselves in its midst. The Association of Independent intellectuals insists upon its main goal, as declared in the program, namely, to bring together »critically oriented public figured who wish to unite their own civil and intellectual engagements with those of other, basically similarly oriented people«. That is why the Belgrade Circle will continue to »promote ideas, deeds and activities that affirm the values of a democratic, civil and plural society...« The Belgrade Circle will »encourage free and critical thought in all spheres of public life. It will support and help institutions and individuals who resist violence and animosity, and who plead for dialogue and for the survival of culture as the only humanly valid way of life«. Fine speeches? Maybe. Nevertheless, the Belgrade Circle has already, and despite many organizational and financial hardships, as well as ugly and unjust abuse from people who should have been, by the very nature of their vocation, in our ranks had they not knuckled under the burden of a more noble – national to be sure – mission, gained an undeniably high reputation. The words uttered with the aim of promoting »Another Serbia« and presented in this book to serve at testimony to the existence of a number of sensible people, shrewd and brave enough to resist suffocation by overwhelming absurdity, were not the only »weapon« used by Belgrade Circle members. They had also an active part in numerous civil and peace movements and events, thus contributing to the establishment of critical public opinion in Belgrade and Serbia: let us recall, for instance, the sad candles and our wake in the park, with souls colder than the Belgrade frost, while one of the past infernal wars – God, which one was it? – was raging out there somewhere; let us recall the »Black Band«, »Yellow Band«, »Student Protest ‘92«, and our endeavours to bring the people of Hrtkovci (»Srbislavci«) to reason; let us recall our guests from Pljevlja, Montenegro, Bosnia... All the time we were just launching our unhappy and, we believe, noble, though perhaps futile venture the very first participant said: let the Belgrade Circle begin it’s work! We hope that by offering this book to the public we have already come a long way. (INTELLECTUALS AND WAR) This volume, Intellectuals and War, follows on the heels of last year’s publication of Another Serbia. Like the latter, it is the result of the work of the Belgrade Circle. As the reader will recall, Another Serbia is a collection of over eighty talks given by members of this association of independent intellectuals and their guests, during ten of the sessions of the Belgrade Circle held every Saturday from the beginning of April to the end of June 1992. Intellectuals and War brings together some fifty texts, which were presented as part of the series »Intellectuals and War« organized every other week, for ten sessions from the beginning of October 1992 until the end of February 1993. At a time when every call for peace, national tolerance, and liberal democracy was being confronted with scorn, disdain, and open ridicule; at a time, that is, when even the most cautious doubts about the utility of the war, which might deflate the state mythology were being denounced as acts of treason committed by slanderers of the National Idea, the Belgrade Circle organized the thematic series, »Another Serbia« and introduced itself to the domestic public as one of the truly rare associations (not to mention political parties, the few exceptions not withstanding) whose members refused on principle to contribute to the destruction of other nations and the demise of their own. With this series and, particularly, with the publication of our book by the same name, the expression »Another Serbia« became a motto for all those who sooner or later came to see the dangers of the nationalist policies of the past five or more years. Unfortunately, many of the dark forebodings expressed in that first series proved to be true. With tragedies mounting at an alarming rate, many words that then sounded very strong, sometimes even, strident, have become but mild reproaches today. Words that once, only a year ago, were just short of blasphemy, have long since become commonplace in the mildest critical discourse in which almost everyone engages. Yet, in looking through the pages of Another Serbia today, one issue emerges from a number of the contributed works that still has not permeated public consciousness deeply enough and has only with great difficulty found its way into the conscience of those individuals to whom it directly refers. This is, of course, the matter of the responsibility of intellectuals for spreading national intolerance, inflaming hatred, advocating war, and – eventually – for instigating crimes and barbaric destruction and causing the isolation, poverty, denigration and scorn which has since come our way. With this in mind, the Belgrade Circle, as an association of – to repeat – independent intellectuals, decided to organize its second thematic series of discussions around this sensitive and uncomfortable question, which is often protected by taboo. The Belgrade Circle did not act impetuously in calling for an open examination of the role of public-opinion makers in the Yugoslav tragedy. Nor did it do so only after having seen the tragic results of conspicuous blunders by writers, scholars, and religious figures in irresponsible national mythmaking or – worse – in open incitement to war. Such a decision was part of the original motivation guiding the future founders of the Circle. Long before the disintegration of the country and before borders were redrawn, territory occupied and people expelled from their homes, they witnessed a number of their colleagues working as free agents or, more often, as institutional propagandists, dutifully reviving national myths, recounting the victims of pats years as if infatuated with death, reworking the ideology of land and blood and skilfully explaining the need for the South Slavic peoples to »separate« from one another once and for all. Seeing this, it became clear to the future members of the Belgrade Circle that it would not be long before these words were turned into deeds. The common denominator for the some twenty philosophers, sociologists, scientists, artists, and journalists who joined together in the Belgrade Circle was, in fact, the decisive refusal to participate in such undignified activities, which could only end in the horrors of war. In its founding Act, and later in number of public statements and individual appearances by its members, the Circle pointed to the responsibility of the »national intelligentsia« and »national institutions« for war and condemned their abuse of public speech. Although against political trials as a matter of principle, the Belgrade Circle argued in its first public statement that not only should politicians, military leaders, and those directly involved in executing their policies be held accountable for their deeds, but also intellectuals responsible for inciting war and causing crimes against humanity, the destruction of cultural and historical treasures, massive displacement of populations and the exile of numerous distinguished creative figures, and the involuntary flight of educated young people. The fact that it was precisely those individuals who given the nature of their work, should have been among our ranks, but chose instead to put their talents, knowledge, and reputation in the service of legitimising a new collectivism, who were the first to poke fun at the Circle and attack it with angry, even threatening messages made it convincingly clear that this important initiative was directed to the right address. At the crucial moment when the class-based identity of society began to collapse from within, these intellectuals, rather then putting their strength and authority into the democratic enlightenment of an apathetic citizenry actively helped to enthrone another new unifying principle, a new unio mistica which would, this time, be based on an artificially awakened and stimulated national identity. Thanks largely to these efforts, the opportunity to become a society of free individuals who act as autonomous citizens in the political sphere and not as anonymous members of the one and only Class, on Nation was again – and, again for a long time – gambled away. Put simply and crudely: once again, »ideologues«, »clerics«, and »guard dogs« have sold us a bill of goods. Few or the participants in the series »Intellectuals and War« were prepared to say that all »national intellectuals« were guided by evil intentions, hatred toward other peoples, vicious greed, futile craving for fame and honour, or the desire to gain the favour of the new/old rulers. It was clear to our authors that there were honest and intelligent people among these »national intellectuals« who sincerely believed that after the fall of the »old regime« it was more important to resolve the national question than to work for the establishment of parliamentary democracy. Reality – as is most often the case – provided them with a real basis for dissatisfaction. However, just as the framers of the idea of the social revolution before them, they turned to the implementation of the national revolution, without paying attention to the means those contracted do to the job – nurtured as they were in our rich tradition – would more than likely use. Thus, it is hard to resist the conclusion that the war began in words. Any rational observer of the now distant events could reasonably have expected the abbreviated series of exchanges between abstract ideas and concrete acts to turn easily and rapidly into bullets. After all, doesn’t the saying go: the pen is mightier than the sword!? A majority of the authors contributing to this volume, share the belief that if intellectuals – who have since become peace advocates – are now amazed and horrified by the sea of spilled blood, the ruined cities and villages, the rivers of displaced and uprooted people, and the previously unimaginable faschisation, impoverishment, and criminalisation of society, they must – if nothing else – face up to their own professional and moral responsibility for this. But this is a question of individual conscience which no one may or should pas a judgment. Some of the text, however, express the belief that another kind of responsibility – one that presumes more tangible consequences than merely having to confront oneself – must surely fall on the shoulders of that »portrait gallery« of our intellectual guard who have consciously advocated war and misted the people, captivating them with otherworldly messages, promising them the heavenly city, submerging them into the past, offering them dignity through force, and turning them away from the most natural desire to live a better and happier life with Others rather than in isolation from the outside world, imprisoned by self-love. One moment openly, the next moment covertly, they supported the consolidation of an authoritarian and indifferent regime, which would carry out the dirty work for them and for the greater glory of the Nation. They graciously allowed the forces of evil to strike, always ready to put the intellectuals’ most daring plans into action. Sometimes participating directly in the government, but more frequently, acting in the shadows as advisors to the absolute ruler and his priests and in collusion with our Volksgeist, these intellectuals were not prepared to take a stand at those moments when the people appeared to have come to their senses. They introduced even greater discord into the already confused political scene as they entered into the ranks of political parties that had the appearance of becoming democratic. Through both their silence and action, they allowed the uneducated electoral body to surrender itself to the one and only real leader. With these texts in front of us, it is tempting to outline a series of »generic-types«, that is, to construct a certain number of »ideal types« from among our national intellectuals. It is easy to understand those readers who would be happy with a string of unique caricature-like portraits. We have merely to think about all those crazed painters, poets of hearth and home, ominous prophets, patented demystifyers of planetary conspiracies and experts in deconstructing the »new world order«, ethno geneticists and amateur historians who trace their nation’s roots to ancient, even prehistoric times, former Marxists who find solace for their collapsed ideology in the »sweet joy of belonging« to the Nation, indefatigable drafters of geopolitical maps, and journalists and columnists who have persistently presented our unsophisticated readers and television audiences with an up side down picture of history and the world. But for now, let’s just keep these in mind: as, in this brief introduction we cannot even hope to sketch out such a typology, much less, to take on a detailed study of some prominent cases. What we can do is hope that a future systematic examination of the role of intellectuals in the wars we are going through will enable us to arrive at an answer to the question posed by the authors of this volume. They themselves have not been motivated by the ambition to offer an answer now and this motivation could hardly be sad to be common denominator among the various texts, which differ both in genre and in the opinions they present. As in Another Serbia, the contributors to Intellectuals and War have their own views and are alone responsible for their words.

More...

Keywords: Serbia; political history; political propaganda; journalism; media; political regime; war; government; media war; international relations; political press;

Prvi moj zadatak u Institutu za novinarstvo bio je da analiziram sadržaj desetak vodećih jugoslovenskih listova prema projektu jednog apoljnjeg saradnika, metodologa, koji je prethodno bio na nekoj specijalizaciji u Americi. Koliko se sećam, glavno moje "otkriće" bilo je da se svi analizirani listovi uređuju po agitpropovskom šablonu - da veličaju politiku vladajuće partije i kritikuju svakog ko se ne slaže sa tom politikom. Novu fazu u mom istraživačkom radu predstavlja ulazak u istorijske arhive, a to se dogodilo krajem šezdesetih, kada sam prijavio doktorsku disertaciju pod nazivom "Počeci političke štampe u Srbiji 1834-1872". Prekopavajući staru arhivsku građu, ustanovio sam da su svi politički listovi onog vremena primali finansijsku pomoć iz državne ili neke druge kase, što znači da su bili u službi propagande. Rezultate istraživanja ubjavljivao sam u svojim knjigama i raznim zbornicima sa naučnih skupova. U poslednjoj deceniji dvadesetog veka Srbija je imala više nedaća nego mnoge evropske države za ceo vek: raspad SFRJ, rat u okruženju, pa rat na sopstvenoj teritoriji, međunarođne sankcije, hiperinfiacija, nezaposlenost, političke svađe i podele. To je i decenija žestokog medijskog rata koji je srpska vlast vodila protiv stranih država i domaće opozicije. [...]

More...

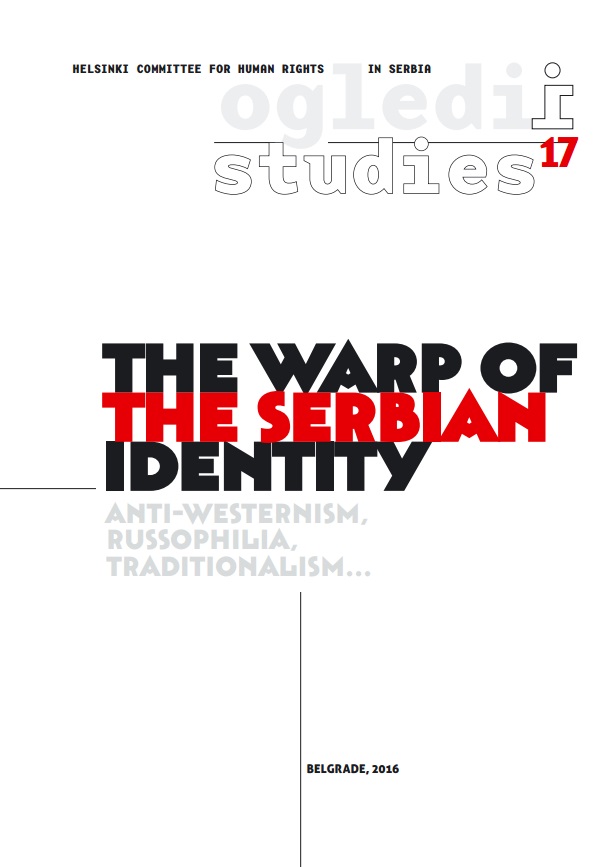

Keywords: Political history; Serbian identity; politics and identity; nation; past; tradition; culture; anti-westernism; political identity;

Problem nacionalnog identiteta postoji, naročito u nedovršenim nacijama, pogotovo tamo gde ne postoji podudarnosti etničkog i državnog aspekta pojma nacije, i tamo gde je taj raskorak traumatičan. Istorijski posmatrano, nacionalni identiteti profilisali su se u okviru zamišljenih zajednica, koje su njeni pripadnici bili spremni da brane po svaku cenu; oni su kao i njihove vođe smatrali da su njihve osnovne odgovornosti – nacionalne. To je možda svojevremeno, bilo neizbežno, ali u globalnom svetu nije dovoljno.U globalnom svetu ljudi pripadaju brojnim zamišljenim zajednicama – lokalnim, regionalnim, državnim, nacionalnim, kosmopolitskim – koje se uzajamno prožimaju, zahvaljujući prvenstveno tehnološkoj komunikacijskoj revolucijii dostupnosti putovanja. Suverenitet nije više apsolut kao što se nekada smatralo. Zbog složenosti problema i okolnosti u kojima Srbija traga za svojim novim identitetom – poraz državnog projekta krajem XX veka i frustracije koja je iz toga proizašla, kao i odgovornošću za rat i ratne zločine koje teško prihvata – Helsinški odbor za ljudska prava se odlučio da priređivanjem zbornika koja je pred čitaocima podstakne raspravu na tu temu. Umesto okretanja modernosti, novi identitet Srbija traži u prošlosti, oslanjajući se na “tradicionalni autentični politički identitet”, odnosno srednjevekovno nasleđe Srbije, pravoslavlje, vizantijsko nasleđe, folklor u kulturi i antizapadnjaštvo. [...]

More...

Keywords: Yugoslavia; Czechoslovakia; political history; 20th century; political system; unity; national framework; culture; identity; Balkans;

A third of my adult life I have lived in what used to be known as the capital of Yugoslavia, Belgrade. The second third I have spent in what was known as Czechoslovakia, in the Moravian city of Olomouc. Yet both countries came into existence and ceased to exist within the 20th century. Many would say that similarities were aplenty. Both countries were formed in the immediate aftermath of the Great War (though Yugoslavia was initially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes), both suffered immensely during World War II, both endured almost half a century of Communist rule, both expired by the end of the century. However, the differences were far greater than the similarities, especially when it comes to the breakup of the two states, as ‘the process of that breakup was vastly different in the two states: it was virtually painless in Czechoslovakia, while it is excruciatingly painful in Yugoslavia’ (Bookman 1994, 175). Much has been written on the two topics, with the death of Yugoslavia probably receiving the most attention, due to the sheer brutality of the bloody breakup during the 1990s, yet a comparative research – to my knowledge – has seen scant attention, with a few notable exceptions (Bookman 1994, Bunce 1999). [...]

More...