We kindly inform you that, as long as the subject affiliation of our 300.000+ articles is in progress, you might get unsufficient or no results on your third level or second level search. In this case, please broaden your search criteria.

The study focuses on a phenomenon that has not yet been dealt with, namelyso-called Young Pioneers’ agricultural farms (pionýrská zemědělská hospodářství) in Czechoslovakia at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s. Their origin is associated with the situation prevailing at that time, when ambitious visions of the soviet leadership were strongly resonating in Czechoslovakia, the process of agricultural collectivization was almost over and, at the same time, the agriculture started suffering from lack of labour. Political and educational authorities were trying tomotivate the young generation to choose a job in agriculture and the concept of the Young Pioneers’ agricultural farms was presented in this context as a “higher-level”hobby for older children. The phenomenon appeared for the first time in southern Slovakia in the spring of 1959 as an initiative of Young Pioneers; as to the Czech Lands, the first farms were set up in the region of Krnov, North Moravia. With the assistance of Local National Committees and regular agricultural cooperatives, the Young Pioneers were supposed to farm hitherto untilled land tracts (grow fruits andvegetables and breed rabbits and poultry) and to establish their “own” agricultura cooperative with child managers. The experiment was also seen as an opportunity to revive the interest of children in activities of the Young Pioneers’ Organization (Pionýrská organizace); as a matter of fact, it made use of children’s self-government elements, which had been often seen in various pedagogical experiments at the turn of the 1940s and 1950s (especially in the attempt to establish the so-called Schoolchildren Community in Krompach, North Bohemia). The establishment of Young Pioneers’ agricultural farms was supported by the Ministry of Agriculture and the leadership of the Czechoslovak Union of Youth (Československý svaz mládeže), which promoted them as a model activity of the Young Pioneers’ Organization. On the other hand, the attitude of the Ministry of Education to the initiative was rather reserved, as children were spending a lot of their free time at the farms both during the school term and during holidays, and there were even critical comments to the effect that the concept was in fact a promotion of small-scale production. The wave of interest finally ebbed in 1963 and 1964 and existing children’s farms were converted into school gardens. The author pays special attention to the model Young Pioneers’ farm in Město Albrechtice in northern Moravia. Thanks to unique school chronicles and a meticulously run school magazine, it was possible to reconstruct the organization of many dozens of children and results of their work, which were rewarded by a high state decoration in 1965. The farm in Město Albrechtice survived until the 1970s thanks to efforts of the local school managers (Karel and Ludmila Schmidtmayers), who were able to motivate a group of children of various ages for voluntary work for the collective. In a way, their concept was ahead of the time and can be compared to the so-called micro-collective movement which was being developed within the Young Pioneers’ Organization in the 1960s.

More...

The text focuses on the possibilities offered by a spatial perspective for the study, teaching, and sharing of experiences with state socialism. The authors offer an insight into the concept developed during the creation of an interactive map. The map aims to visualize the Communist Party’s attempt to interpret Czechoslovak history in the public environment. The relics of its cultural policy in the current public sphere present opportunities for the use of the map in education.

More...

This article examines the reaction of Dragiša Stojadinović to the feuilleton “Serbian themes” done by the writer Miroslav Krleža. Krleža’s feuilleton was being published in newspaper Politika during April, May and June of 1963. It consisted of fragments from his earlier writings organized in thematic units and concerning different topics from Serbian history. Dragiša Stojadinović, former soldier, chief of Cinematographic section of Serbian army on Salonica front during the First World War and politician in interwar Yugoslavia, responded to Krleža’s feuilleton by writting an Open letter to the Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts (Zagreb), the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (Belgrade) and the Matica Srpska (Novi Sad). Stojadinović’s Open letter was sent on June 28th, 1963. It focused on scrutinizing Krleža’s article Pašić about the Salonika trial published in Politika on June 9th. Both informations stated by Krleža and criticism put forward by Stojadinović are analyzed in the light of contemporary historiographical knowledge. Different interpretations presented by Krleža and Stojadinović have their roots in opposed views on causes and results of Salonika trial. Stojadinović defended the legitimacy of trial started by his father-in-lawLjuba Jovanović Patak, he was involved in its organisation and later accused of witness tampering. Krleža saw trial in the light of “counter-revolutionary” Yugoslav unification in 1918 and as an act of “political and judicial murder”. Article also contains original documents from National Library of Serbia.

More...

Until the summer of 1944 Romania and Hungary had been each other’s enemies within the same federal bond. In late summer 1944 the ruling elite in Bucharest went over from the Axis powers falling apart under Hitler’s reign to the Allied powers’ side standing to win. In Budapest Regent Miklós Horthy’s failed attempt to withdraw Hungary from the war brought into power a far-right ephemeral regime, which sticked with Hitler to the very end. Nevertheless, as they were and stayed neighbours in the same front-zone, later they drifted into a defeated position as collateral losers in a very similar way. From a geopolitical aspect both countries got into the sphere of interest of the Soviet Union. Initially, Stalin did not plan an immediate Bolshevization in either case. However, in both cases a change of regime was conducted from Moscow, in which the local communist parties were made a Grecian Horse within the initially multiparty forced coalition. The wartime cooperation of the supreme powers turned into a cold-war opposition, amidst which the military and political supremacy of the Soviet Union became determinant. The differences of domestic policy and the current conflicts of interest of the two countries became fading couleur locale sceneries on Stalin’s regional stage of the „new European order”. From the turn of 1947/48 on, there was only a few months’ difference in the process of the communist party’s exclusive takeover in the countries of the region, including Romania and Hungary as well.

More...

In the wake of the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the Hungarian leadership considered the new socialist giant as the empire of opportunities. During the Cold War, however, the level of Sino–Hungarian bilateral trade relations always lagged behind Hungarian expectations. What was the reason for this mismatch between expectations and realities? How did the development of Sino–Soviet relations and the Soviet intention to control their satellites influence the opportunities for bilateral economic relations and the total volume and commodity structure of bilateral trade? And to what extent could Hungarian economic policies promote specifically Hungarian interests under Soviet rule? This article attempts to answer these questions, based, due to the lack of Chinese archival materials, primarily on Hungarian foreign ministry and party documents.

More...

The 1956 Hungarian revolution had a resonant echo in Western Europe, gaining large attention and media coverage. This article explores how the small, peripheral Atlantic country of Portugal, on the other side of the European continent (Lisbon lies more than 3,000 kilometers from Budapest), which was under the rightwing conservative dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar’s New State at the time, became interested in the Hungarian events, allowing them to be written about in the most influential newspapers. The article begins with a discussion of the basic context of the Hungarian revolution of 1956 and of the Portuguese political context in the mid-1950s (the Salazarist regime and the bulk of the oppositional forces) and then offers an analysis of articles found in seven important Portuguese newspapers. Essentially, it presents a survey of the coverage of the Hungarian Revolution in the Portuguese press and explores how those events were interpreted and how they had an impact on the ideological readings and positions of the government, the moderate opposition, and the radical opposition of the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP). The 1956 revolution merited extensive coverage in the Portuguese papers, with titles, pictures, and news boxes on the front pages sometimes continuing into the next pages of a given paper or on the last page. The stories were narrated, for most part, in a lively, fluid, sentimental, and apologetic language. The New State in particular, but also moderate publications which were oppositional to Salazar, endorsed the Budapest revolutionaries and criticized and denounced orthodox communism in the form of Soviet repression, either in the name of Christendom, national independence, and the Western European safeguard against communism (in the case of Salazarism), or in the name (and hope) of a democratic surge, which would usher in strident calls for civil liberties (in the case of oppositional voices). With the exception of the press organ which voiced the official position of the Portuguese Communist Party, supporting the Soviet response against the Hungarian insurgents (and thus was in sharp contrast with the larger share of public opinion), there was a rare convergence, despite nuances in the language, in the images, narratives, messages, and general tone of the articles in the various organs of the Portuguese press, which tended to show compassion and support for the insurgents in Budapest because their actions targeted communism and tended to decry the final bloody repression, which exposed the Soviet Union as a murderous regime.

More...

The extreme right political forces, which had escaped to Western Europe after World War II, reorganised themselves some years later as a movement. They constantly prepared for the comeback, to win back political authority in Hungary. The perfect opportunity seemed to have come with the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. They let the occasion slip, however, without any effective intervention in the course of events. Thereafter, they merely focussed on influencing those who had fled from Hungary, and on propagating the ideology.

More...

The goal of this paper is to shed light on the circumstances surrounding the murder of four and wounding of three members of the Yugoslav Federal Militia Special Unit on May 13, 1981, in the village of Donje Prekaze in Drenica (SAP Kosovo). An attempt to bring Tahir Meha to serve a two-month prison sentence turned into an exchange of fire during which Tahir and his father Nebih were killed. In the years that followed a myth has been spread among Albanians about the life and heroic death of Tahir Meha, which was then built into the foundations of the Albanian separatist movement and attempts to build the statehood of Kosovo. Extensive archival material collected after the skirmish reveals the true events behind the myth.

More...

From October 20 to 27, 1984, an assembly of the Association of Yugoslav Volunteers of the Spanish Republican Army was held in Sarajevo from which an open letter was sent to the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. This paper (re)constructs a chronology of events, following the thoughts and activities of Konstantin Koča Popović, which he wrote in his diary (from August 1984 to February 1985) during the preparations for the Sarajevo meeting, as well as his reactions to the talks held by representatives of the CC LCY and members of the Board of the Association. Today, the diary notes of Koča Popović are kept in the Family Fund – Legacy of Koča Popović and Lepa Perović in the Historical Archive of Belgrade.

More...

The topic of this paper are the dynamic relations between Yugoslavia and the Socialist International in 1951–1954. These relations are considered through the possibility of Yugoslavia joining the Socialist International, as well as separate events that had significantly influenced their development: the case of Živko Topalović, the interference of the Socialist International in the Trieste crisis and the reactions of the Socialist International to Yugoslavia’s growing engagement with the Third World.

More...

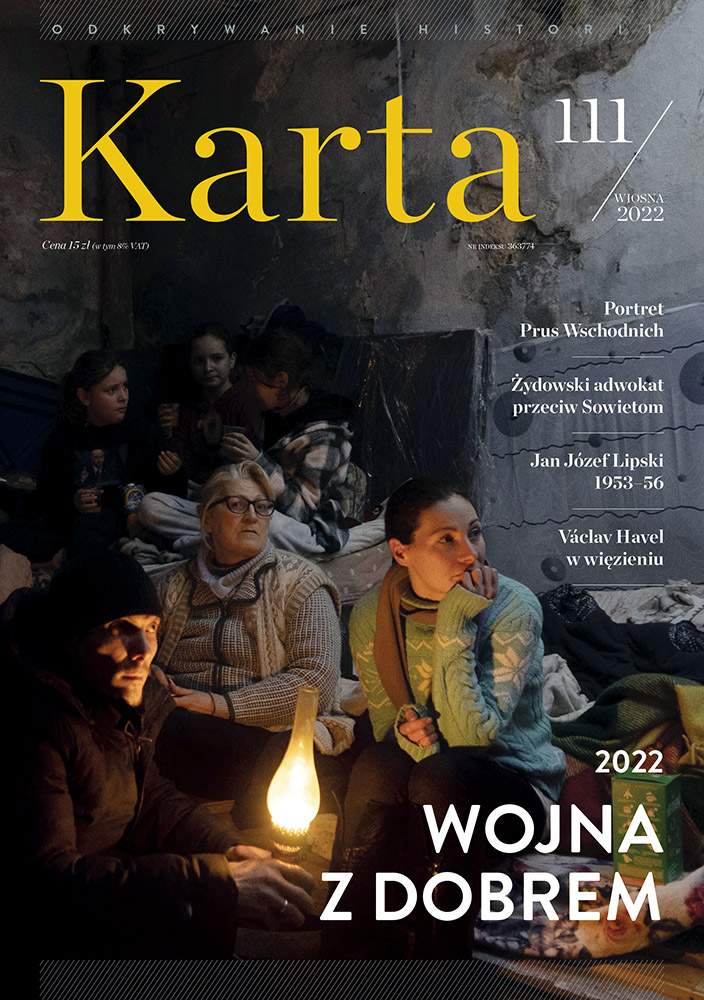

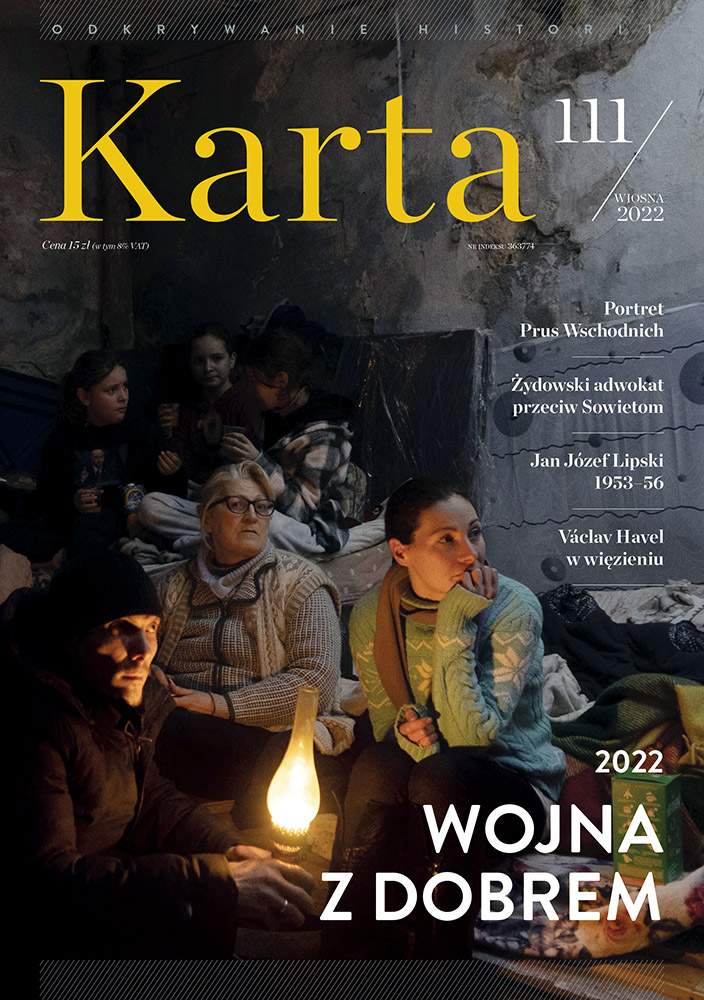

Czas po śmierci tyrana w zapiskach przenikliwego obserwatora. Time after the tyrant's death in the notes written by a keen observer.

More...

Uwięzienie czołowego opozycjonistypo zbiorowym akcie oporu wobec reżimukomunistycznego w styczniu 1977. The imprisonment of a leading oppositionistafter a collective act of resistance to the regimecommunist in January 1977

More...

The Soviet Union and Cold War Neutrality and Nonalignment in Europe. Edited by Mark Kramer, Aryo Makko, and Peter Ruggenthaler. Lanham MD: The Harvard Cold War Studies Book Series, Lexington Books, 2021. 627 pp.

More...

Western Europe’s Democratic Age, 1945–1968. By Martin Conway. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020. 357 + xii.

More...

The subject matter of the article is the regulation of war damage issues with states which have attacked Yugoslavia in the last world war. The issue has been completely settled as far as Italy and Hungary are concerned by means of relevant bilateral treaties. On the other hand, there is no legal ground for obtaining reparation from Bulgaria since it had been forgiven to that country' by a unilateral declaration of Yugoslav government in 1947. and that in spite of a July 1991 declaration on annulling that decision made by the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia. The author discusses recent exchange of diplomatic notes between Yugoslavia and FR of Germany concerning war damage regulation. According to the Aide-Memoire of November 1973 (published in the article) "the SFR of Yugoslavia government accepts in principle the proposal by the government of the FR of Germany to compensate by the amount of one billion German Marks in the form of assistance in capital (Kapitalhilfe) the damage sufferred by Yugoslav victims of Nazi repressiion". According to the author, regardless of this document, the issue of war damage with Germany is still open, since it covers only a part of damages, and not the entire material and other war damage. Thus the 1972 and 1947 Treaty concerning the assistance in capital is only an attempt at solving the entire issue, to be followed by new agreements. The author also refutes by legal arguments the Note of German government of April 23, 1992 refusing further negotiations with Yugoslavia. Particularly important is, for instance, the issue of compensation for forcible labour of prisoners of war during the 1941-1945 period, since both countries are the signatories of the 1929 Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War.

More...

Příspěvek vídeňských menšinových archivů k historii sociálně demokratického exilu: výběr z korespondence Josefa Jonáše a Radomíra LužiStudie s komentovanou edicí dokumentů je věnována sociálně demokratickému novináři, politikovi a funkcionáři Josefu Jonášovi (1920–2002). Tohoto předního činovníka české demokratické komunity ve Vídni 2. poloviny 20. století představuje především v kontextu jeho aktivit v československém sociálně demokratickém exilu po únoru 1948. Text se zaměřuje zejména na období od Jonášova útěku z Československa do přelomu 50. a 60. let. Z té doby také pocházejí čtyři dopisy, které autoři předkládají v komentované edici. Soubor je zajímavý především proto, že přibližuje aktivity Josefa Jonáše v rámci exilu, ozřejmuje pozadí jeho přesunu z Kodaně do Vídně a naznačuje jeho vztahy k dalším výrazným osobám exilového života. Dopisy jsou dochovanou částí korespondence mezi Jonášem a Radomírem Lužou, jenž byl jeho blízkým přítelem a exilovým spolupracovníkem. V roce 1960 se Luža z New Yorku přesunul za Jonášem do Vídně a strávil tam s rodinou šest let. Zatímco Radomír Luža je již historikům čs. exilu (nejen skrze jeho autorské práce) dobře znám, osobnost Josefa Jonáše je v rámci studií exilu dlouhodobě přehlížena (vyjma souvislostí s exilovými aktivitami Bohumila Laušmana). Jeho činnost nejen v rámci sociálně demokratického exilu, ale i v širším kontextu (spoluzakladatel a člen redakční rady časopisu Svědectví, člen Rady svobodného Československa, Československého poradního sboru v západní Evropě aj.) ukazuje, že tato osobnost rozhodně není bez významu a zaslouží si vědeckou pozornost.

More...

The concept of selective development of Polish industry in the 1970s assumed significant structural transformations in the industry related to the modernization of industrial production. The most intense structural changes took place in the first stage of industrialization and were related to the construction of the foundations of a relatively developed industrial complex. The intensity of structural changes in this period, measured by the average coefficient of relative structural transformations, was extremely high. In the years 1960–1970, the intensity of changes in the branch structure of production was much lower than in the previous period. The mechanical and chemical industries continued to show a significant increase in their share in global industrial production, although the growth rates of the above-mentioned industries in relation to the overall growth rate were lower than in 1950–1960. With the transition to the next stages of industrial development, changes in the intra-industry structure of production within individual industries, especially within the so-called leading branches. Structural aspects of economic and industrial growth have not been the subject of detailed economic research for a long time, especially from the point of view of treating these changes as an independent factor of contemporary economic development. Specialized industrial development was treated as a condition for maintaining production at a high technical level, and thus as a condition for the development of trade exchange and cooperation in the field of industrial production.

More...