We kindly inform you that, as long as the subject affiliation of our 300.000+ articles is in progress, you might get unsufficient or no results on your third level or second level search. In this case, please broaden your search criteria.

Sándor Vadász was 80 years old in 2010. His colleagues greeted him with studies. At the end of the volume there is an interview with professor Vadász about his life.

More...

The book presents the results of new research in Slovak history in the field or period called “the long 19th century”, i.e. dating from the rule of Joseph II. in the late 18th century until the First World War. The focus of research was on the themes and domains which were either neglected in the past or needed reconsidering. The book centres on five fields and is composed of five chapters. The first chapter is called “The Nation and the national issue”. It presents new aspects by exploring one of the most principal themes of 19th century. In his study, László Vörös reflects about the modern concept of the nation, which won recognition by the most contemporary historians, ethnologists and sociologists: the nation as an imagined community and an imagined tradition which is connected with the modernisation epoch. Nationalism is specifically an urban phenomenon. In the Slovak historiography, the national movement had been explored mostly in the rural area, in the peasant milieu, because the majority of the Slovak ethnic population was composed of peasants. Eva Kowalská aimed to change this perspective and concentrated on explaining urban aspects of Slovak nationalism. In case of Slovakia, these aspects are more interesting since the Slovaks in the 19th century had no important central city, and only small towns in the countryside (like Turčiansky Sv. Martin), had tried to compensate this lack. In his contribution, Peter Macho summarises how the symbol of the Tatra mountains as well as other Slovak geographic-territorial symbols were present in the Slovak nationalist discourse. Peter Šoltés elaborates on the theme and the activities of the Slovak Evangelical intelligentsia in the first half of the 19th century. The second chapter “The National movement in foreign and domestic politics” deals with the important connection of nationalism and politics. Slovak foreign political thought was traditionally orientated toward the Russian Empire. In his contribution, Dušan Kováč shows the other side of the Slovak foreign orientation: their attitude to the Western powers England and France. Dušan Škvarna attempts at a reconsideration of the role and inspiring function of the Slovak National Council, established during the 1848 revolution. The Swiss political scientist Josette Baer, a specialist in the field of Slavonic and lately mainly of Slovak political thought, presents her analysis of the early political activities of Vavro Šrobár (an important personality of Slovak politics in the 20th century), especially his leading role in the so-called “Hlasist movement”. The third chapter is dedicated to the juridical system and economic issues. Tomáš Gábriš presents a very useful survey of the juridical system in Hungary and its changes in the era of modernization during the 19th century. His paper shows that in Hungary the tendency to modernize was clashing with very difficult obstacles, mainly ideological and political ones. The attempt to create the centralised “nation state” in Hungary restrained the most important liberal-democratic reforms of the juridical system. In her contribution, Eva Ondrušová deals with the traditional studies of economic cameralism and its influence on the economic theory and practise in the 19th century. Ľudovít Hallon and Miroslav Sabol follow the history of the Pittel and Brausewetter architectural company, which was much closely connected with and active in the very broad Pressburg (Bratislava) area. Very new themes are presented in the forth chapter named “Society, social life and environment”. Gabriela Dudeková outlines the system of poor relief in the Habsburg monarchy; her focus is on the mechanisms how the authorities denied social care to specific groups in Hungary. Slovak emigration to America is a very traditional issue in Slovak historiography. Igor Harušťák tries to consider this problem in the broader Central- and East-European context. Prior to 1989, research about the nobility as a social strata was neglected in Slovak historiography. Even after 1989, this theme was intensively researched mainly in the period of middle ages and the early modern times. However, from the social point of view, important and interesting issues are e. g. the nobility’s life style as well as the attempts of these “high society” members to preserve their status in the modern 19th century. Daniel Hupko deals with these issues focussing on the example of Lucia Wilczek. Roman Holec presents a completely new approach in his contribution about the changes in the relationship ‘man – animal’ as manifestation of a new attitude to nature during the 19th century. The last chapter of this volume is dedicated to “The Churches in the social – modernizing processes “.Ingrid Kušniráková analyses the controversial interferences of Joseph II. into the life of the Roman Catholic Church, especially the closing-down of some cloisters. Tomáš Králik focuses on the relations of the Vienna court to the St. Elisabeth convent in Pressburg (Bratislava). The chapters of this collective monograph will serve as a basis for the draft of a new synthetis on Slovak history in the “long 19th century”.

More...

Bratislav Ivanov's new book is dedicated to the values and traditions of the Japanese culture. Already in the early twentieth century, French scientist Henry Dumolard draws attention to the fact that the Japanese people are guided by their logic and draw conclusions that are often incomprehensible to Europeans. To understand the Japanese people, we need to know the values that form the core of their culture. A key to their understanding is the geographical environment, mythology, religion, and Japan's history.

More...

The book studies the Ancient Egyptian religion. The author describes the creation and its driving forces through the view of Egyptian concepts. The idea of God and the divine manifestations, the place of man in the world and the ways to achieve immortality are explored. The exposition is based on the study of ancient hieroglyphic texts and is illustrated with numerous examples. The book is intended for a wide range of readers who are interested in the religion and culture of Ancient Egypt. It contains three chapters: the world of gods, the creation of the world and the world of men. Special attention is paid on the concept of the kingship in Ancient Egypt. The Egyptian terminology and the names of gods and goddesses are formed as a dictionary at the еnd of the book.

More...

This modern translation of all the surviving literary compositions ascribed to Liudprand, the bishop of Cremona from 962 to 972, offers unrivaled insight into society and culture in western Europe during the "iron century". Since Liudprand enjoyed the favor of the Saxon Roman emperor Otto the Great, and traveled to Constantinople more than once on official business, his narratives also reveal European attitudes toward the Byzantine Empire and the culture of its refined capital city. No other tenth-century writer had such privileged access to the high spheres of power, or such acerbic wit and willingness to articulate critiques of the doings of powerful people. Liudprand's historical texts (the Antapodosis on European events in the first half of the 900s, and his Historia Ottonison the rise to power of Otto the Great) provide a unique view of the recent past against a genuinely European backdrop, unusual in a time of localized cultural horizons. Liudprand's famous satirical description of his misadventures as Ottonian legate at the Byzantine court in 968 is a vital source of information on Byzantine ritual and diplomatic process, as well as a classic of medieval intercultural encounter. Readers interested in medieval European culture, the history of diplomacy, Italian and German medieval history, and the history of Byzantium will find this collection of translated texts rewarding. A full introduction and extensive notes help readers to place Liudprand's writings in context.

More...

„The Prince” was written by Niccolo' Machiavelli in the 1500s. It has continued to be a best seller in many languages. The Prince is a classic book that explores the attainment, maintenance, and utilization of political power in the western world. Machiavelli wrote The Prince to demonstrate his skill in the art of the state, presenting advice on how a prince might acquire and hold power. Machiavelli defended the notion of rule by force rather than by law. Accordingly, The Prince seems to rationalize a number of actions done solely to perpetuate power. It is an examination of power-its attainment, development, and successful use.

More...

Evliya Celebi was an enlightened man in a variety of ways who believed in equality, freedom of thought and intellectual debate, and found all of these things present in Islamic societies. Over the course of his travels, he wrote ten volumes detailing his adventures. ‘Seyahatname’ – Book of Travels – is a unique and important text, representing one of the few accounts of the 17th century and the Ottoman world from the perspective of a Muslim. These are not just factual accounts, Evliya had a great imagination and just as important as his journal entries were the imaginative storytelling that ran alongside, elaborating, exaggerating, and fantasizing. Through his stories, we are prompted to think more imaginatively about our own travels and journeys to other cities. This 17th-century Muslim traveler can sometimes seem narrow-minded and yet this same man can stand in St Stephens Cathedral in Vienna and be moved by the music he hears. Sometimes these encounters lead to nothing but sometimes they lead to stories which are so deeply felt, and so universally melodic that they leave echoes which can still be heard and felt today. In 2011, the year which would have been his 400th birthday, Evliya is being paid homage as UNESCO’s Man of the Year.

More...

The subject o f this scholarly meeting is summarized in its title which gives the best possible formula of all topics dealt with in the said projects. Our goal is to see that, after the first year of work on the projects, these two research and education institutions organize a transparent conference which would provide access to the entire experience related to the project activities and to the results achieved by the research workers after a year-long effort. In the course o f such presentations, a need will arise for a critical overview and discourse o f all the issues and dilemmas encountered hitherto by the scholars. From the very start o f the sign-up period, in July 2001, the problems have, unfortunately, emerged in the formulation of entries in pursuance of the instructions in the project registration form. These were not the only nor the biggest problems. A prolonged waiting for the foreign reviews and for the allocation of research time, which w as considerably reduced as concerns our Institute, resulted in a 30% reduction of funding, and in a year-long struggle to get reimbursement for direct material expenses. Everyone is aware that such projects in the humanities, which have then special national significance, cannot be even conceived o f without fieldwork. As a matter o f principle, it should be pointed out here that the attitude to the humanities has, in the case o f our projects, proved inadequate. After this first year o f research work, in which a number o shortcomings has crystallized as being inappropriate to the nature and spirit o f the humanities, we do hope that in the ensuing stages such shortcomings will be eliminated. W e expect understanding and support from our financier. I am sure that today ’s presentations, a long with the afore said, and in combination with individual experiences acquired by the scholars during their research work in 2002, w ill yield a fruitful discussion which, as a rule, is the best achievement of such symposia.

More...

Upravo doneti Zakon kojim se rehabilituju svi “ideološki” protivnici komunizma, počinje sa datumom od 6. aprila 1941. što je istovremeno i njegov najzanimljiviji deo. Imali smo priliku da slušamo predlagače i zagovornike zakona1 koji su svojom srčanom odbranom ratnih “ideoloških” protivnika komunizma, nedvosmisleno potvrdili da je čitava stvar i smišljena isključivo zbog njih, a da ih oni posle 1945. ustvari i ne zanimaju, odnosno, da su samo “kolateralna šteta” pokušaja rehabilitacije kvislinga iz vremena Drugog svetskog rata. Saopštili su nam i da bi čitav komunistički period trebalo jednostavno proglasiti zločinačkim čime bi, misle oni, po automatizmu bili rehabilitovani svi njegovi “ideološki” protivnici, a oni ratni proglašeni borcima za pravednu stvar. Zato možemo očekivati da će (kao što se već desilo sa četnicima) ovog puta “demokratama” biti proglašeni nedićevci i ljotićevci, pa će po automatizmu “demokrate” postati i balisti, hortijevci, ustaše, i na kraju, sam nemački Rajh. Svi oni zaista jesu bili “ideološki” protivnici komunizma, ali je, sasvim sigurno, Hitler bio najveći. Zato nije slučajno danas, njihov “ideološki” antikomunizam i početak i kraj svake argumentacije, uz prećutkivanje da su kao protivnici komunizma bili i aktivni protivnici celokupne antihitlerovske koalicije čiji je komunizam bio sastavni deo. Prećutkuje se i da je njihov “ideološki” antikomunizam u tadašnjem shvatanju pojma podrazumevao veličanje nacizma, antidemokratiju, i na prvom mestu, antisemitizam, “slučajno”, baš u vreme kada su milioni Jevreja ubijani u “Velikom Nemačkom Rajhu”.

More...

(ANOTHER SERBIA) Every Saturday for a period of two months, from the beginning of April till the end of June 1992, sessions organized by the Belgrade Circle were held at the Student Cultural Centre in Belgrade. At these sessions, ten in all, intellectuals, members of the Belgrade Circle and their quest – distinguished writers, scientists, artists, journalists, film and theatre directors, architects, actors, interpreters – expressed their own views of another, radically different Serbia. In times of anguish and affliction, the meetings, attended by a large assembly of listeners experiencing a kind of moral purification, were nonetheless imbued with a frail hope that there still might be a chance for a turn in events. With a desire to present ideas, opinions and sensations shared by the participants of the Belgrade Circle sessions to a much larger audience, the reading public, and to preserve them, because of their merit, in a more lasting form, discussions of over eighty intellectuals were compiled to form this book. In the meantime, the overwhelming disaster has reached its climax: »The Bosnian War«, still raging with no feasible way out as yet, exploded and blazed up like fire. The Belgrade Circle participants, distressed and abashed at the display of all those real or imagined evil deeds, so eagerly reported by the portentous heralds of death voiced hitherto often deeply hidden and silent feelings and thoughts about their burdensome disgust at the plague gripping and afflicting us all. Each participant contributed in his or her own way – rigorous scientific analysis, artistic susceptibility, eyewitness accounts, or simply. A public-minded desperate wail – to the shaping of one new, public opinion, the one that stirred in that sad Spring of ’92 and rebelled against the general fear, animosity, devastation, extermination, ethnic cleansing, forcible population exchanges... All those responsible and public-minded citizens, holding different political opinions, some members of various political parties, with incomparable personal experiences, varied professional interest and often of »objectionable« national origin, showed, however the will to insert tolerance among the basic principles of a humanized way of fife. But, in spite of the pronounced differences, their common aim, discernable in each and every speech imported to the audience, was to finally establish a community based on simple but as yet still unattainable ideals such as peace, freedom, tolerance and justice in place of degrading political, national and religious exclusiveness. Participants focussed their attention on various aspects of the problem: some analysed the roots of hatred and evil; some indicated the disastrous consequences of irresponsible national myth revivals; others warned of menaces yet to come unless we see reason in time. Some were stern, others witty and others still perhaps too prone to pathos, but they were all deeply concerned, and, as it unfortunately turned out, correct in predicting subsequent events. Therefore, individuals who take no notice of current, official policy and who have for a long time now tenaciously refused to render their talent and knowledge to the needs of the authorities, gathered round a project titled »Another Serbia«. Instigating a state of war and providing alleged erudite justification for the necessity of mutual extermination in the name of some noble goals, vague even to the very massacre executors, must not and cannot be the vocation of anyone who considers him or herself an »intellectual«, or earns a living acting as one. Hence, all session participants had but one desire: to mark out a path that may lead into a more promising future, to another, different, better and happier Serbia. »Another Serbia« soon became the synonym of resistance to fabricated lies, nationalistic madness, criminal war, a fascist holocaust, senseless destruction of villages and cities. Thanks are also due to the daily newspaper »Borba« which regularly reported on the Belgrade Circle Saturday sessions, and published a number of contributions presented there... We hope that the Another Serbia we all aspire to be easily discernable in the collection of essays presented in this book. The reader who hopes to find traces of at least some political program will be gravely disappointed. At present, when politics have poisoned the very soul of so many men of letters and knowledge, and when, among the most violent oppressors, in the ranks of all mortal enemy groups, one finds so many proud bearers of scientific degrees, who may actually be designated as men of unmerited and easily squandered reputation, it has become somewhat indecent to praise »intellectual pursuits«. The Belgrade Circle was, however, founded early in 1992 with the aim of retrieving dignity – another dangerous quality! – to public speech and conceived plans of action for the benefit of truth. We do not take an elitist position and stand indifferently above the crowd. On the contrary, being deeply involved and concerned, we place ourselves in its midst. The Association of Independent intellectuals insists upon its main goal, as declared in the program, namely, to bring together »critically oriented public figured who wish to unite their own civil and intellectual engagements with those of other, basically similarly oriented people«. That is why the Belgrade Circle will continue to »promote ideas, deeds and activities that affirm the values of a democratic, civil and plural society...« The Belgrade Circle will »encourage free and critical thought in all spheres of public life. It will support and help institutions and individuals who resist violence and animosity, and who plead for dialogue and for the survival of culture as the only humanly valid way of life«. Fine speeches? Maybe. Nevertheless, the Belgrade Circle has already, and despite many organizational and financial hardships, as well as ugly and unjust abuse from people who should have been, by the very nature of their vocation, in our ranks had they not knuckled under the burden of a more noble – national to be sure – mission, gained an undeniably high reputation. The words uttered with the aim of promoting »Another Serbia« and presented in this book to serve at testimony to the existence of a number of sensible people, shrewd and brave enough to resist suffocation by overwhelming absurdity, were not the only »weapon« used by Belgrade Circle members. They had also an active part in numerous civil and peace movements and events, thus contributing to the establishment of critical public opinion in Belgrade and Serbia: let us recall, for instance, the sad candles and our wake in the park, with souls colder than the Belgrade frost, while one of the past infernal wars – God, which one was it? – was raging out there somewhere; let us recall the »Black Band«, »Yellow Band«, »Student Protest ‘92«, and our endeavours to bring the people of Hrtkovci (»Srbislavci«) to reason; let us recall our guests from Pljevlja, Montenegro, Bosnia... All the time we were just launching our unhappy and, we believe, noble, though perhaps futile venture the very first participant said: let the Belgrade Circle begin it’s work! We hope that by offering this book to the public we have already come a long way. (INTELLECTUALS AND WAR) This volume, Intellectuals and War, follows on the heels of last year’s publication of Another Serbia. Like the latter, it is the result of the work of the Belgrade Circle. As the reader will recall, Another Serbia is a collection of over eighty talks given by members of this association of independent intellectuals and their guests, during ten of the sessions of the Belgrade Circle held every Saturday from the beginning of April to the end of June 1992. Intellectuals and War brings together some fifty texts, which were presented as part of the series »Intellectuals and War« organized every other week, for ten sessions from the beginning of October 1992 until the end of February 1993. At a time when every call for peace, national tolerance, and liberal democracy was being confronted with scorn, disdain, and open ridicule; at a time, that is, when even the most cautious doubts about the utility of the war, which might deflate the state mythology were being denounced as acts of treason committed by slanderers of the National Idea, the Belgrade Circle organized the thematic series, »Another Serbia« and introduced itself to the domestic public as one of the truly rare associations (not to mention political parties, the few exceptions not withstanding) whose members refused on principle to contribute to the destruction of other nations and the demise of their own. With this series and, particularly, with the publication of our book by the same name, the expression »Another Serbia« became a motto for all those who sooner or later came to see the dangers of the nationalist policies of the past five or more years. Unfortunately, many of the dark forebodings expressed in that first series proved to be true. With tragedies mounting at an alarming rate, many words that then sounded very strong, sometimes even, strident, have become but mild reproaches today. Words that once, only a year ago, were just short of blasphemy, have long since become commonplace in the mildest critical discourse in which almost everyone engages. Yet, in looking through the pages of Another Serbia today, one issue emerges from a number of the contributed works that still has not permeated public consciousness deeply enough and has only with great difficulty found its way into the conscience of those individuals to whom it directly refers. This is, of course, the matter of the responsibility of intellectuals for spreading national intolerance, inflaming hatred, advocating war, and – eventually – for instigating crimes and barbaric destruction and causing the isolation, poverty, denigration and scorn which has since come our way. With this in mind, the Belgrade Circle, as an association of – to repeat – independent intellectuals, decided to organize its second thematic series of discussions around this sensitive and uncomfortable question, which is often protected by taboo. The Belgrade Circle did not act impetuously in calling for an open examination of the role of public-opinion makers in the Yugoslav tragedy. Nor did it do so only after having seen the tragic results of conspicuous blunders by writers, scholars, and religious figures in irresponsible national mythmaking or – worse – in open incitement to war. Such a decision was part of the original motivation guiding the future founders of the Circle. Long before the disintegration of the country and before borders were redrawn, territory occupied and people expelled from their homes, they witnessed a number of their colleagues working as free agents or, more often, as institutional propagandists, dutifully reviving national myths, recounting the victims of pats years as if infatuated with death, reworking the ideology of land and blood and skilfully explaining the need for the South Slavic peoples to »separate« from one another once and for all. Seeing this, it became clear to the future members of the Belgrade Circle that it would not be long before these words were turned into deeds. The common denominator for the some twenty philosophers, sociologists, scientists, artists, and journalists who joined together in the Belgrade Circle was, in fact, the decisive refusal to participate in such undignified activities, which could only end in the horrors of war. In its founding Act, and later in number of public statements and individual appearances by its members, the Circle pointed to the responsibility of the »national intelligentsia« and »national institutions« for war and condemned their abuse of public speech. Although against political trials as a matter of principle, the Belgrade Circle argued in its first public statement that not only should politicians, military leaders, and those directly involved in executing their policies be held accountable for their deeds, but also intellectuals responsible for inciting war and causing crimes against humanity, the destruction of cultural and historical treasures, massive displacement of populations and the exile of numerous distinguished creative figures, and the involuntary flight of educated young people. The fact that it was precisely those individuals who given the nature of their work, should have been among our ranks, but chose instead to put their talents, knowledge, and reputation in the service of legitimising a new collectivism, who were the first to poke fun at the Circle and attack it with angry, even threatening messages made it convincingly clear that this important initiative was directed to the right address. At the crucial moment when the class-based identity of society began to collapse from within, these intellectuals, rather then putting their strength and authority into the democratic enlightenment of an apathetic citizenry actively helped to enthrone another new unifying principle, a new unio mistica which would, this time, be based on an artificially awakened and stimulated national identity. Thanks largely to these efforts, the opportunity to become a society of free individuals who act as autonomous citizens in the political sphere and not as anonymous members of the one and only Class, on Nation was again – and, again for a long time – gambled away. Put simply and crudely: once again, »ideologues«, »clerics«, and »guard dogs« have sold us a bill of goods. Few or the participants in the series »Intellectuals and War« were prepared to say that all »national intellectuals« were guided by evil intentions, hatred toward other peoples, vicious greed, futile craving for fame and honour, or the desire to gain the favour of the new/old rulers. It was clear to our authors that there were honest and intelligent people among these »national intellectuals« who sincerely believed that after the fall of the »old regime« it was more important to resolve the national question than to work for the establishment of parliamentary democracy. Reality – as is most often the case – provided them with a real basis for dissatisfaction. However, just as the framers of the idea of the social revolution before them, they turned to the implementation of the national revolution, without paying attention to the means those contracted do to the job – nurtured as they were in our rich tradition – would more than likely use. Thus, it is hard to resist the conclusion that the war began in words. Any rational observer of the now distant events could reasonably have expected the abbreviated series of exchanges between abstract ideas and concrete acts to turn easily and rapidly into bullets. After all, doesn’t the saying go: the pen is mightier than the sword!? A majority of the authors contributing to this volume, share the belief that if intellectuals – who have since become peace advocates – are now amazed and horrified by the sea of spilled blood, the ruined cities and villages, the rivers of displaced and uprooted people, and the previously unimaginable faschisation, impoverishment, and criminalisation of society, they must – if nothing else – face up to their own professional and moral responsibility for this. But this is a question of individual conscience which no one may or should pas a judgment. Some of the text, however, express the belief that another kind of responsibility – one that presumes more tangible consequences than merely having to confront oneself – must surely fall on the shoulders of that »portrait gallery« of our intellectual guard who have consciously advocated war and misted the people, captivating them with otherworldly messages, promising them the heavenly city, submerging them into the past, offering them dignity through force, and turning them away from the most natural desire to live a better and happier life with Others rather than in isolation from the outside world, imprisoned by self-love. One moment openly, the next moment covertly, they supported the consolidation of an authoritarian and indifferent regime, which would carry out the dirty work for them and for the greater glory of the Nation. They graciously allowed the forces of evil to strike, always ready to put the intellectuals’ most daring plans into action. Sometimes participating directly in the government, but more frequently, acting in the shadows as advisors to the absolute ruler and his priests and in collusion with our Volksgeist, these intellectuals were not prepared to take a stand at those moments when the people appeared to have come to their senses. They introduced even greater discord into the already confused political scene as they entered into the ranks of political parties that had the appearance of becoming democratic. Through both their silence and action, they allowed the uneducated electoral body to surrender itself to the one and only real leader. With these texts in front of us, it is tempting to outline a series of »generic-types«, that is, to construct a certain number of »ideal types« from among our national intellectuals. It is easy to understand those readers who would be happy with a string of unique caricature-like portraits. We have merely to think about all those crazed painters, poets of hearth and home, ominous prophets, patented demystifyers of planetary conspiracies and experts in deconstructing the »new world order«, ethno geneticists and amateur historians who trace their nation’s roots to ancient, even prehistoric times, former Marxists who find solace for their collapsed ideology in the »sweet joy of belonging« to the Nation, indefatigable drafters of geopolitical maps, and journalists and columnists who have persistently presented our unsophisticated readers and television audiences with an up side down picture of history and the world. But for now, let’s just keep these in mind: as, in this brief introduction we cannot even hope to sketch out such a typology, much less, to take on a detailed study of some prominent cases. What we can do is hope that a future systematic examination of the role of intellectuals in the wars we are going through will enable us to arrive at an answer to the question posed by the authors of this volume. They themselves have not been motivated by the ambition to offer an answer now and this motivation could hardly be sad to be common denominator among the various texts, which differ both in genre and in the opinions they present. As in Another Serbia, the contributors to Intellectuals and War have their own views and are alone responsible for their words.

More...

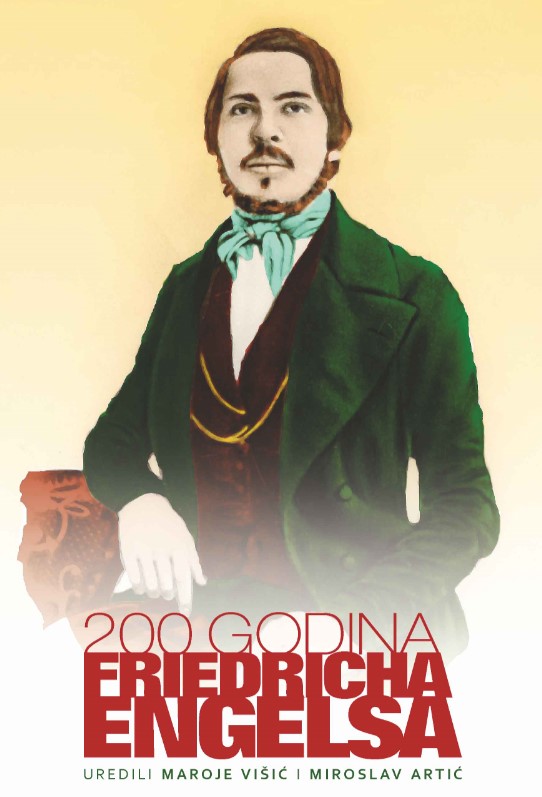

This anthology book is published on the occasion of the bicentennial of the birth of Friedrich Engels, an exceptional thinker and theorist of the revolution. Editors Maroje Višić and Miroslav Artić gathered renowned domestic and international scientists who tried to reevaluate Engels' works and his scientific contribution. The idea behind the book is to point out the everlasting value and significance of Engels’ revolutionary philosophy. Contributing authors offered analytical reading of Engels' ideas, addressing pressing issues in economics, politics, religion, feminism, ideology and in other segments of contemporary society. The papers in an anthology are organized under the chapters: The Reception of Engel’s Philosophy, Actuality of Engels Today with subchapters on working-class and precariat, peasantry as the subject of change, early Christianity as an inspiration; and the last chapter is Revalorization of Family and State. The first chapter tackles the questions if Engels was more than an interpreter of Marx or simply the first Marxist who contributed to the banalization of Marx. It then investigates reception of Engels’ philosophy in ex-Yugoslavia specifically and in philosophical theory in general. The second chapter demonstrates actuality and relevance of Engels today by discussing the topics of working-class and precariat, by making comparison between early industrial society and contemporary society and by tracking development of socialism from utopia to a science. Chapter also deals on the peasantry whose role as a subject of change is thoroughly problematized. Special part of the chapter is dedicated to the influence of the practice of early Christianity on the formation of Engels’ revolutionary idea and to what extent original Christian community served affected the development of Engels’ thought. Final chapter brings papers that, under new circumstances, re-examine the understanding of the state-family relation and their dynamic. This comprehensive anthology attempted to revalorize and appraise Engels’ own contribution to science and philosophy 200 years after his birth. For this it was necessary to “divorce” Engels from Marx so that the fallacy of statement that Engels was second violin to Marx becomes striking.Chapter one tackle the question of whetherEngels was more than an interpreter of Marx or simply the first Marxist to contribute to the banalization of Marx.= Engels' reception is then examined both in the former Yugoslavia and in philosophical theory in general.Special part of the chapter is dedicated to influence of the practice of early Christianity on the formation of Engels’ revolutionary idea. That is, to what extent the examples of the original Christian communities influenced the development of Engels' thought

More...

U ovoj knjizi donosimo transkript nekoliko izlaganja sa konferencije koju je Documenta organizirala u Zagrebu u rujnu 2013. godine s ciljem predstavljanja višegodišnjeg snimanja i objave intervjua na web stranici www.osobnasjecanja.hr. Uz komentare i pitanja nekih od sudionika konferencije, u knjizi možete pročitati uvodni tekst koji je na konferenciji izložila urednica kolekcije Maja Dubljević, te transkript izlaganja Vesne Jakumetović iz Vukovara, Ane Raffai iz Zagreba, te Đorđa Gunjevića iz Pakraca. Predstavljamo vam i dvije studije slučaja u kojima su korišteni snimljeni intervjui - studiju slučaja publicistkinje i istraživačice, Vesne Kesić „Španovica / Novo selo / Španovica: Znalo se? Nije se znalo?“ te studiju slučaja povjesničara Marka Smokvine “Stara Gradiška kao paradigma hrvatske povijesti 20. stoljeća”.

More...

The lexicon is divided into four chapters. The first one is a detailed introduction, where we present a professional background of our topic, the significance of our research, the structure of our work, as well as the used literature and sources, in addition to an overview of the Arab-Hungarian relations. In the second and longest chapter, we portray biographies of the Arab personalities. In the third one, we examine the most important historical events in the Arab world, such as the Arab-Israeli wars, the nationalization of the Suez Canal, and the parallel crisis of 1956. In the last chapter, we briefly introduce concepts related to the stories and biographies found in the volume.Only a few results of Arabic historiography have been integrated into modern Hungarian research. Therefore, we consider it a priority to fill this gap. The aim of this work is to create a lexicon in which we gather – in the form of articles – the most eminent Arab personalities (approximately 1000), who were/are decisive in political, economic, military or even cultural life and others associated with the Arab world.

More...

Ideja o pisanju knjige i pokretanju projekta o srpsko-albanskim odnosima javila se, kako to na Balkanu često biva, u kafani (koja je, doduše, u neposrednoj blizini Narodne biblioteke Srbije). Pošto su se u Betonu pojavili tekstovi Milana Miljkovića o predstavljanju Albanaca u srpskoj štampi i Aleksandra Pavlovića o figuri Turčina kao neprijatelja, Milan je uz čašicu predložio da se inicira projekat koji bi okupio srpske i albanske intelektualce, teoretičare i teoretičarke u oblasti društvenih nauka koji bi zajedno obrađivali srpsko-albanske odnose. Verovatno je najčešći način borbe protiv politika neprijateljstva začudna i retka politika prijateljstva. Tako je bilo i u slučaju Aleksandra Pavlovića i Rigelsa Halilija, koji su zbog sličnosti u naučnim temama i interesovanjima najpre uspostavili „naučno pobratimstvo“, a ubrzo došli i do nekolicine drugih srpskih i albanskih kolega zainteresovanih da učestvuju u ovom projektu. Da sve ne ostane na kafanskoj priči (što na Balkanu takođe često biva) zasluga je i urednikā Betona, prevashodno Saše Ćirića, koji je kumovao projektu i knjizi predloživši njen naziv Figura neprijatelja: preosmišljavanje srpsko-albanskih odnosa, a obezbedio je i pomoć prevodilačke mreže Traduki koja je odmah prihvatila da sufinansira prevođenje tekstova sa srpskog na albanski jezik i obrnuto. Usledilo je nekoliko neuspelih inicijativa sa domaćim institucijama – naši prijatelji iz albanskog Ministarstva kulture rekli su nam da misle da za ovako nešto još nije vreme, a na konkursu srpskog Ministarstva kulture uprkos obimnoj dokumentaciji koju smo poslali u traženih 7 (i slovima sedam) primeraka (!), projekat na godišnjem konkursu nije dobio ni dinara. Za razliku od rečenih institucija, kolege iz Instituta za filozofiju i društvenu teoriju, pogotovo sadašnje koordinatorke projekta i kourednice ove knjige Gazela Pudar Draško i Adriana Zaharijević, uz mentorstvo Petra Bojanića, založile su se za projekat i značajno ojačale prvobitnu aplikaciju, koja je zatim podržana u okviru švajcarskog Programa za promociju istraživanja na zapadnom Balkanu koji finansira Švajcarska agencija za razvoj i saradnju, na čemu im dugujemo veliku zahvalnost. Pored IFDT-a i KPZ Beton, saradnici na projektu su i „Ćendra multimedija“ („Quendra Multimedia“) iz Prištine, koja je 2011. godine zajedno sa KPZ Beton objavila antologije Iz Prištine, s ljubavlju (o savremenoj kosovskoj literaturi na albanskom jeziku) i Iz Beograda, s ljubavlju (o savremenoj prozi mlađih autora u Srbiji), i „Poeteka“ iz Tirane, ugledni izdavački i kulturni centar koji kontinuirano objavljuje prevode savremene i ranije srpske književnosti na albanski jezik.

More...

The 𝑇𝑎𝑟𝑛𝑜𝑣𝑜 𝐿𝑖𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑎𝑟𝑦 𝑆𝑐ℎ𝑜𝑜𝑙 collections contain reports from the recurrent international symposium “Tarnovo Literary School”, which is the oldest and most respected forum on Old Bulgarian studies in Bulgaria and worldwide. It was held for the first time in 1971 under the auspices of UNESCO, and the first collection of articles came out in 1976. The𝑇𝑎𝑟𝑛𝑜𝑣𝑜 𝐿𝑖𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑎𝑟𝑦 𝑆𝑐ℎ𝑜𝑜𝑙 collections are among the most cited editions in the fields of Old Bulgarian studies and research into medieval Bulgarian spiritual and material culture from its pre-Tarnovo and Tarnovo periods, as well as on the cultural and literary ties between Byzantium, Bulgaria, and the Eastern Orthodox Slavic world. The main purpose of 𝑇𝑎𝑟𝑛𝑜𝑣𝑜 𝐿𝑖𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑎𝑟𝑦 𝑆𝑐ℎ𝑜𝑜𝑙 is to publish scholarly articles by Bulgarian and foreign researchers in the field of interdisciplinary medieval studies in order to explore the cultural and historical heritage of the Second Bulgarian Empire.

More...

On the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the death of Dr. Franjo Tuđman, the first director of the Institute for the History of the Workers' Movement of Croatia and the first president of the independent, contemporary and democratic Republic of Croatia, the Croatian Institute of History organized a scientific conference on December 10 and 11, 2009. Dr. Franjo Tuđman in Croatian Historiography. Although Dr. F. Tuđman is better known and more interesting to the general public as a politician and statesman, and although his work as a historian and politician is difficult to separate, the organizers of the scientific conference focused on the work of Dr. F. Tuđman as a historian, wanting scientists, primarily historians and political scientists, from scientific novices to academics, sine ira et studio, through selected topics to approach a comprehensive questioning of the significance and influence of Dr. F. Tuđman on the historiography of modern Croatian history.

More...

The book before you is dedicated to our dear colleague and friend Zef Mirdita. In this way, we want to thank him for his exceptionally fruitful, almost 50-year scientific work, and especially for the days he has spent and still spends with us at the Croatian Institute of History in Zagreb from 1993 to the present day. Professor Mirdita has also been an honorary member and advisor of the Albanian Institute (Albanisches Institut) in St. Gallen (Switzerland) since its foundation in 2002. Although he retired in 2004, the scientific community of the Croatian Institute of History will always consider him its distinguished member whose research results are an indispensable part of not only Croatian and Albanian but also European historiography. His life and scientific path took place (and still actively takes place) between Croatia and Albanians (especially Kosovo).

More...

The book Beyond Anthropocentrism, i.e. Demand for the Impossible? The Questions of Culture and Other Questions in Social Theory and Practice of Conversation concentrates on man and his psycho-physical condition, taking special account to its ethical consequences for the world and himself. However, the book also tries to make him leave his privileged status. The monograph is divided into three parts. Chapter 1: Culture in Theory presents essential findings focused on the key term, “culture”. Chapter 2: Culture in Practice presents seven in-depth interviews conducted in the years 2020–2021 with the researchers representing a spectrum of different scientific disciplines: Ewa Bińczyk, Katarzyna Dembicz, Bogumiła Lisocka-Jaegermann, Joanna Ostrowska, Hanna Rubinkowska-Anioł, Jolanta Sujecka, Anna Ziębińska-Witek. In Conclusion, the fundamental problem of the posthumanistic (non-anthropocentric) vision of the world is paid attention to.

More...